In April of 2003, epidemiologist Brigg Reilley, a program officer for Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), returned from an assessment of MSF's HIV/AIDS prevention programs in Humera. The study examined whether MSF's voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) and sexually transmitted infections (STI) programs were successful with the migrant groups that bear the most risk of infection.

|

|

His story is an old one.

Haftey, whose name means "Wealth," came to Humera in northeastern Ethiopia for the money. He heard the rumor, uttered many times, in many different languages, of a place where a young man can prosper.

The hot, arid climate provides an optimal environment for growing sesame, sorghum and cotton, which is why this region has been called the Ethiopian breadbasket. Unfortunately, it also provides a perfect home for the sand flies that prey on those who work the fields, infecting migrant workers, who sleep in the open, with the deadly visceral leishmaniasis parasite.

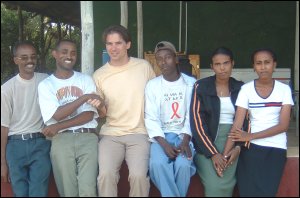

Brigg Reilley with the MSF team in Humera. Photo © MSF |

Besides seasonal farm workers, Humera also draws other transitory groups - soldiers guarding the Eritrean border, a large number of long-distance truck drivers, and the employees of a bustling commercial sex trade. All of which accelerates the rapid spread of HIV/AIDS in the region.

For Haftey and many of the 80,000 other young men who flood the region each harvest season, rumor quickly gives way to fact: instead of riches, they find a wealth of sickness and destitution.

In April of 2003, epidemiologist Brigg Reilley, a program officer for Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), carried out a month-long an assessment of MSF's HIV/AIDS prevention programs in Humera. The study examined whether MSF's voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) and sexually transmitted infections (STI) programs were successful with the migrant groups that bear the most risk of infection.

The study confirmed MSF's suspicions: people knew about the services offered by MSF, but a vicious cycle of sickness, stigma, and fatalism was preventing many in Humera from protecting themselves against disease.

MSF's ARV treatment project will transform AIDS from a death sentence to a manageable chronic disease. Although still months away, there are already signs that giving Humerans a reason to have hope will also give them a reason to be tested, removing some of the denial from the disease in the public eye.

"We found that the people who were actively seeking testing and counseling were those who were concluding a risky chapter in their life, and starting a new one," said Reilley. "Soldiers who were being discharged from the military and going home. People who had reason to hope for a better, safer future."

Based on the results, MSF will expand its prevention activities in the region and set the groundwork for an AIDS treatment project to begin distributing antiretroviral (ARV) drugs later this year. This will be on top of the medical, nursing, and nutritional care MSF has been providing at Humera's hospitals and clinics for several years.

"For a lot of these men, all they have to do is get HIV and they're hopelessly behind in the cycle," said Reilley. "They won't leave, or can't leave, until they make some money, but they can't make money if they're sick. If they test positive for HIV, they'll be seen as immoral and contagious. In all likelihood they'll die slowly and alone. I think in many ways it's quite understandable that they don't want to know that they have the disease."

According to Reilley, there's a ray of hope in the apparently bleak picture. As MSF's kala azar intervention has given people hope of beating the disease, the disease's harmful associations have dissipated.

Humera, Ethiopia, photo taken by Brigg Reilley. Photo © MSF |

"These days, there's no stigma in kala azar because there is treatment available," said Reilley. "No sense that a person with the disease is to be avoided - and not as much hopelessness if you do have it. People come to the clinic to be tested."

Young men like Haftey will always flock to Humera to chase a promise that may never be fulfilled. While MSF's infectious disease interventions won't bestow wealth, Reilley hopes the improved health care will help many realize the possibility of better things to come.