In Haiti, the first survey of deaths resulting from violence in more than a decade reveals the extreme levels of bloodshed in Cité Soleil, an impoverished neighborhood in the capital, Port-au-Prince.

The retrospective mortality survey was conducted by Epicentre, the epidemiology and medical research branch of Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), in Cité Soleil between July 25 and August 24, 2023, during a truce negotiated between the gangs that fight each other on a daily basis in the streets of Port-au-Prince.

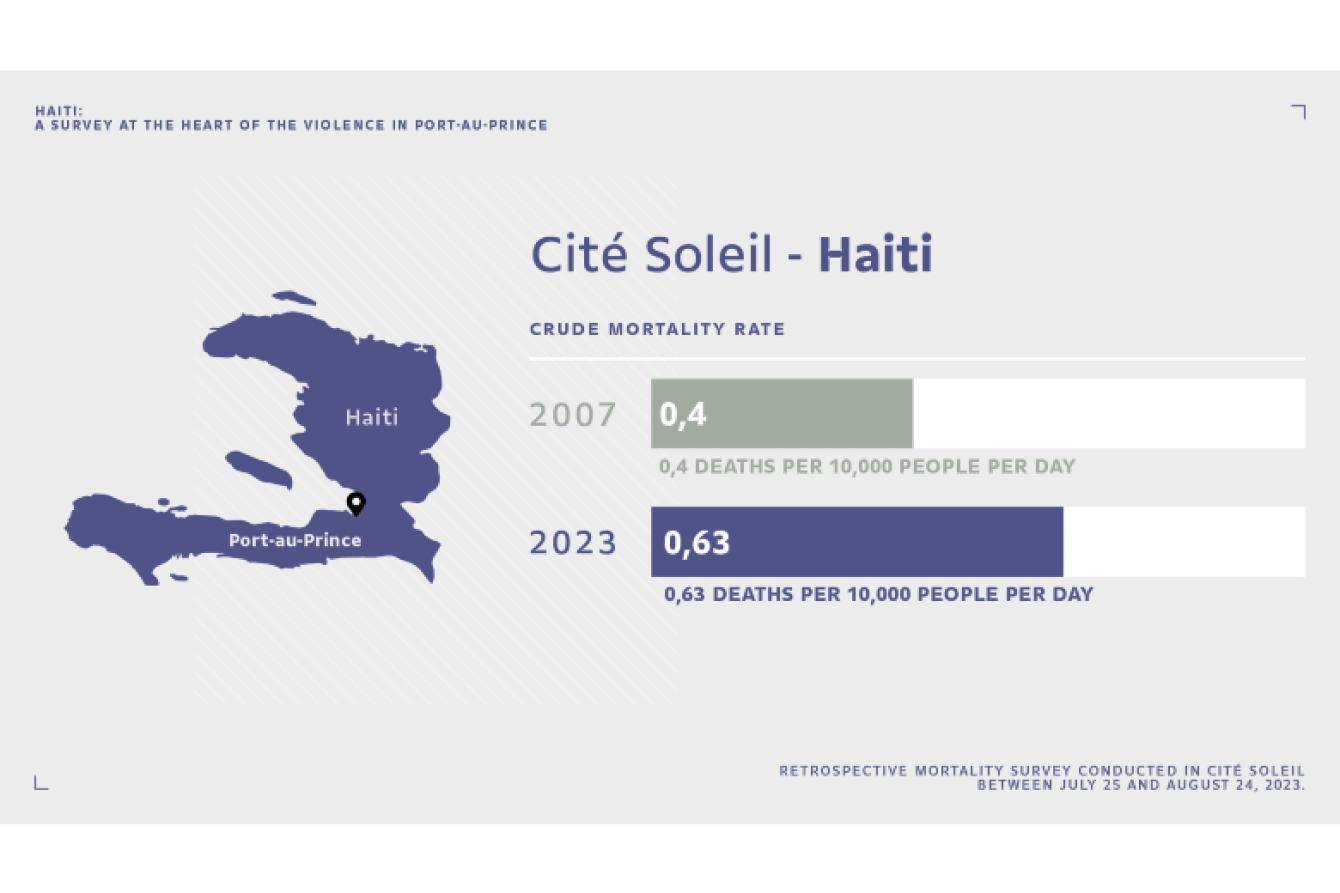

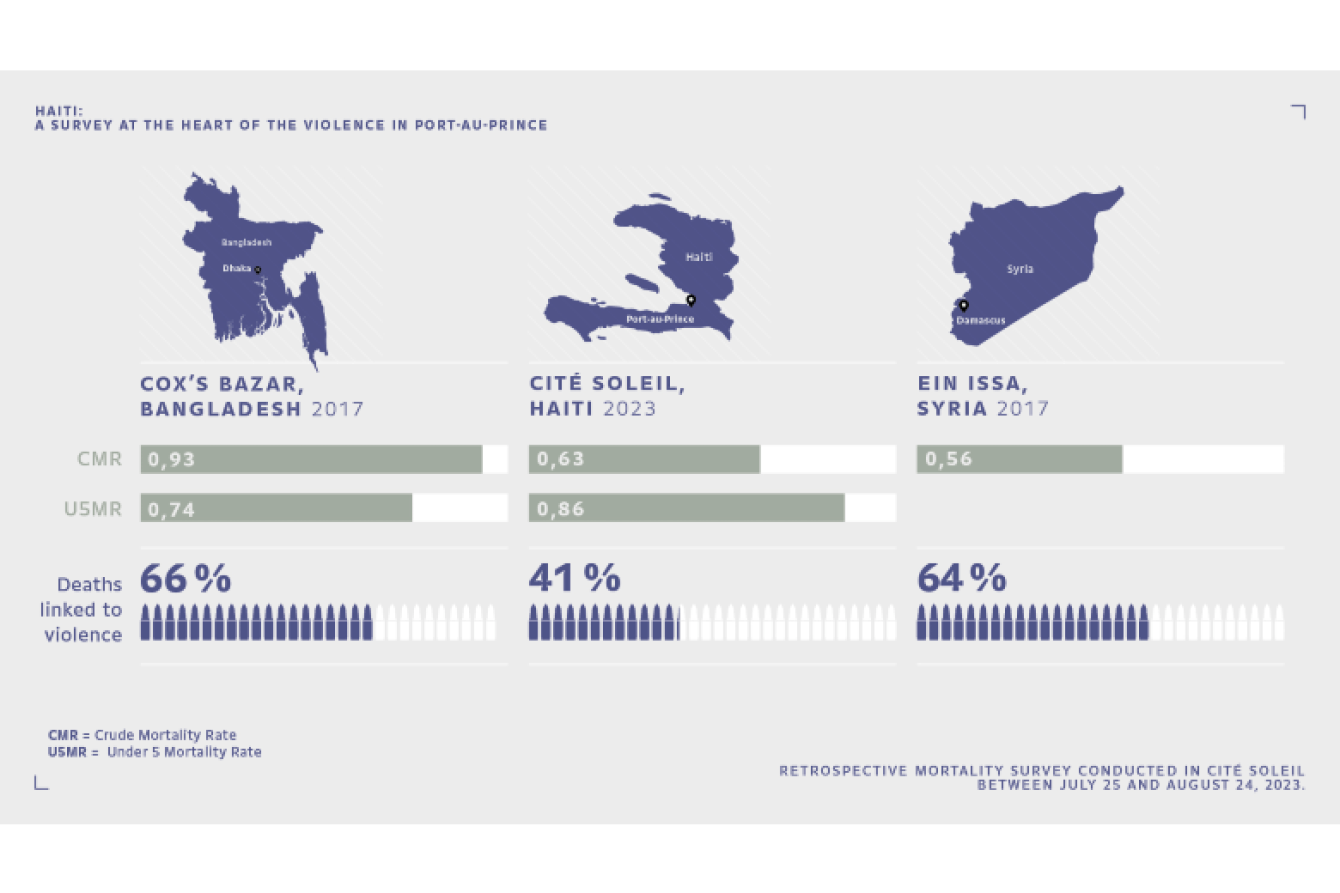

The results highlight an abnormally high mortality rate, with more than 40 percent of all deaths caused by violence. In comparison to a similar but less extensive study conducted by MSF in the same area in 2007—when the fighting had already begun—the survey shows an alarming increase in mortality from violence.

In addition to experiencing violence, 13 percent of Cité Soleil residents surveyed reported witnessing extreme violence in the streets, including murders and lynchings.

“My sister was robbed at gunpoint twice. My cousin was robbed once and so was another cousin. I’ve been caught in the crossfire of confrontations with the police and other clashes. People always ask me: 'What are you still doing in Haiti?’ I say: ‘Well, I don't want to leave.’ But at some point, resistance will be futile. At the end of the day, most Haitians don’t need to be rich. We don’t need that. We want to live well. We want to have a better life.”

“I’m used to seeing people killed. I’m used to seeing bodies lying on the ground. I’m used to seeing burnt corpses. I’m used to seeing everything in fact, you know. I’m used to hearing bangs, all kinds of bangs. Sometimes it’s someone you know. Sometimes it’s someone you don’t know who has died as a victim of violence (...) When I talk about terror, I’m talking about armed violence. I’m talking about physical violence. I’m talking about psychological violence. I’m talking about poverty. I’m talking about killings. I’m talking about gang violence against people.”

In comparison to previous MSF retrospective mortality surveys conducted, the crude mortality rate (the number of deaths per 10,000 people per day) in Cité Soleil is close to the rates seen in the Islamic State stronghold of Raqqa, Syria in 2017 and in Myanmar in 2017 as the Rohingya people fled campaigns of targeted violence by the military.

A descent into chaos

Almost three years after the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse, the people of Port-au-Prince are struggling to survive amid clashes between armed gangs, police, and civilian self-defense brigades. According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), at least 806 people were killed, injured, or kidnapped in Haiti in January 2024, considered the most violent month in more than two years. Since then, the situation has deteriorated even further, and on February 28, Port-au-Prince descended into chaos again, with dozens of injured people crowding MSF facilities.

Figures from a few telephone surveys of residents of Port-au-Prince corroborate the MSF survey’s findings among residents of Cité Soleil. Epicentre also carried out a study among Haitian MSF staff in 2023 that confirmed a high level of exposure to extreme violence. Nearly half of the households included in these two surveys were affected by one or more forms of violence.

“It was April 12. My daughter was going to school and I went to drop her off. When we arrived outside the school, a girl was kidnapped with one of her parents. It was quite difficult. They had to send all the pupils home. At the time, the only thing on my mind was to protect my daughter, who was in the back of the car. I was ready to do anything. Then, when we got home, I was in a total panic. A thousand thoughts went through my head. If I had arrived 30 seconds earlier, it would have been me, because the car was just in front of me. I wouldn't wish that on anyone.”

Haiti: MSF scales up medical response amid chaos in Port-au-Prince

Read more“It goes on all day long. We now have murders, burglaries, truck hijackings, rapes, and all that. I moved at one point and then came back afterwards because apartments were too expensive. But in 2018 I had to move again because things were really difficult. My wife was pregnant. We were due to have a child and because of the violence, I had to move again to avoid the risks for my wife.

"Now I live like a nomad. I don’t have a fixed place to live at the moment and my wife and children are living at my mother-in-law’s ... Sometimes I stay at my workplace, sometimes I move around a bit and go to other places to sleep at friends’ houses, where it’s quieter. Every day is stressful. Not being with your family and not being close to your children all day long means feeling the stress every day.”

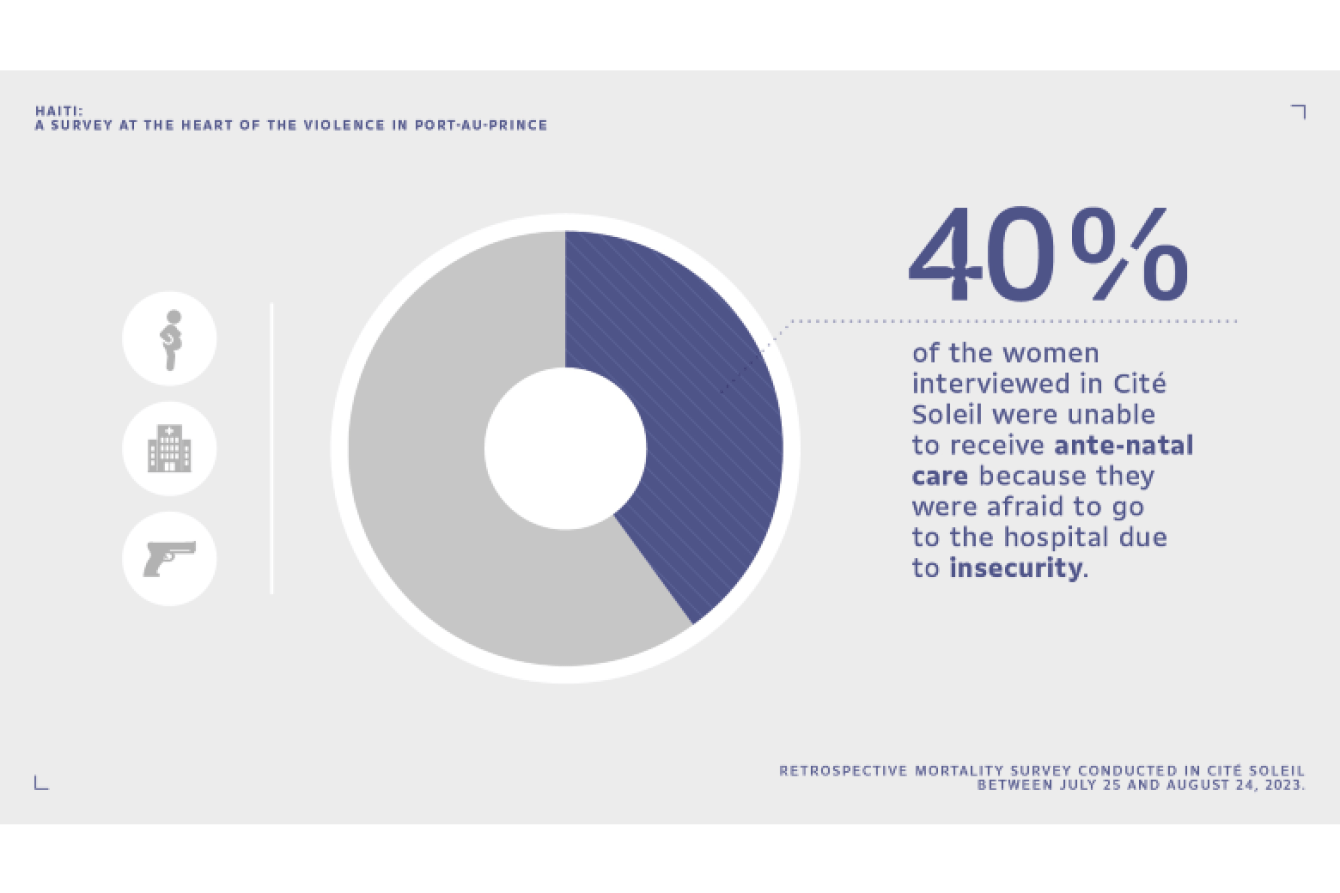

Since 2021, this violence has led to the displacement of more than 150,000 people, who are living in precarious conditions in camps. Going to the doctor or school or work has become extremely dangerous and people risk their lives when they do so. According to the MSF survey, 40 percent of women interviewed in Cité Soleil did not receive prenatal care because they were afraid to go to hospital due to the insecurity.

“I had to send my family to Santo Domingo. And the worst thing, the thing that affects me the most, is that my wife was seven months pregnant. So the baby, my princess, has been born and I’ve never seen her... She’s seven months old.”

Figures are likely a significant underestimate

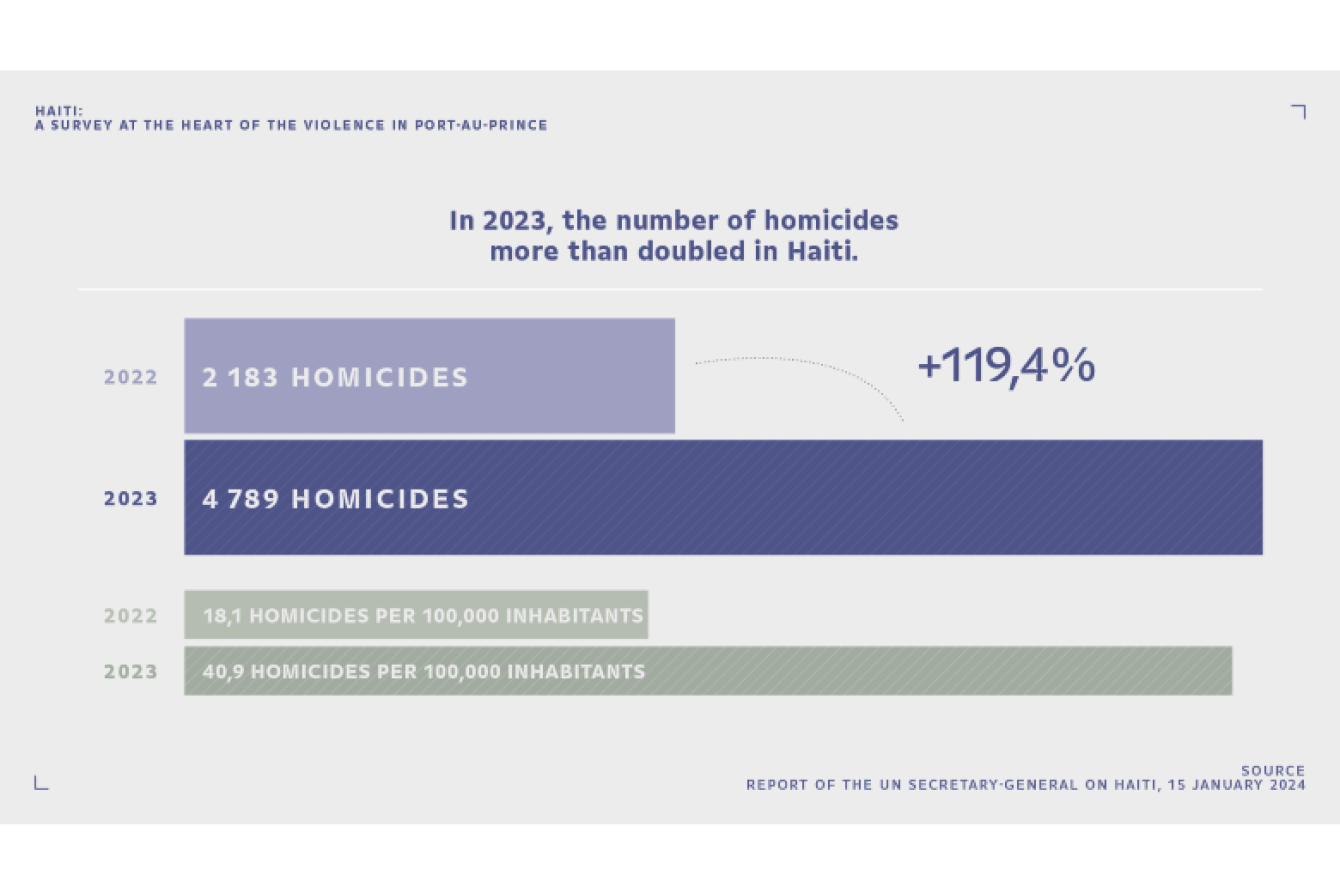

In 2022, Haiti ranked 21st among countries with the highest intentional homicide rates, just behind Venezuela, while Port-au-Prince had the 20th-highest homicide rates (excluding war zones) among cities. In 2023, the number of homicides in Haiti more than doubled, with over 4,700 victims, showing a considerable increase in violence. Also in 2023, kidnappings increased by 83 percent compared to 2022.

These figures appear to be substantial underestimates in comparison to the 2,300 violent deaths recorded in the MSF survey for Cité Soleil alone, which is home to just 9 percent of the population of the Haitian capital. This underestimate has been documented in several reports, including a thesis published in 2016 which suggested that the homicide rate in Haiti is underestimated by at least 70 percent.

“When you’re a father and you see a two-year-old girl who has come in with a gunshot wound, it really shocks you. And when you see schoolchildren who are passing by and who have nothing to do with armed groups, who are shot at and who have bullets in their bodies, that really shocks you as well.”