On September 19, United Nations (UN) member states came together to formulate a more “coordinated and humane approach to address large movements of refugees and migrants," according to the New York Declaration that was ratified today at the UN's Global Summit on Refugees and Migrants.

Many of the right things were said before and during the summit, but it's the follow up, the actions taken, that will dictate how much those words mean for the more than 65 million people displaced globally—the most there have been since World War II. Many concerns have already been expressed. Based on what our teams are seeing while providing emergency medical care to displaced people the world over, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has its own as well. The declaration aims for “concrete results in 2018,” which may be too long for many to wait. And some of the same states that ratified the declaration have been implementing increasingly harsh, restrictive, and often inhumane policies around refugees and migrants. Will this change anything?

And at all times, we must remember who we are talking about: men, women, and children who've been forced from their homes by war, privation, persecution, or some other crisis. Listed below are just some of the contexts in which MSF works, where the struggle to survive goes far beyond even the best intentions.

SYRIAN REFUGEES IN THE BERM

On June 21, in the name of national security, Jordan closed its northern border with Syria after a car bombing targeted a Jordanian military base near an area referred to as "The Berm." This left 75,000 people—four out of five of whom are women and children—stranded in the desert without assistance, with insufficient access to water, and with almost no access to food [in early August, UN agencies, using a crane, conducted a drop-off of food supplies intended to last one month]. The Berm is not a refugee camp, but rather an ad hoc settlement of people fleeing war where no one would choose to reside. No humanitarian aid organizations are currently able to provide assistance, meaning inhabitants of The Berm lack basic humanitarian services.

From May 16 to June 21, MSF was able to access the population trapped at The Berm. MSF teams saw patients with chronic conditions and serious life threatening diseases—such as diabetes, heart conditions, cancer, and congenital abnormalities— all of which require medical care to keep the patients alive. Our teams conducted 3,501 consultations and treated more than 200 malnourished children [10 of whom were severely malnourished] and 450 pregnant women, some of whom were high risk pregnancies. One baby was delivered.

The population is stuck in an extremely harsh environment without access to vital humanitarian assistance and still vulnerable to violence from Syria. The protection and the humanitarian and legal needs of the refugees must be the sole consideration for solving their isolated and dangerous living situation. The provision of humanitarian aid to The Berm must be allowed to resume, although the resumption of emergency aid is not a long-term solution, and leaving people to suffer in the desert is unacceptable.

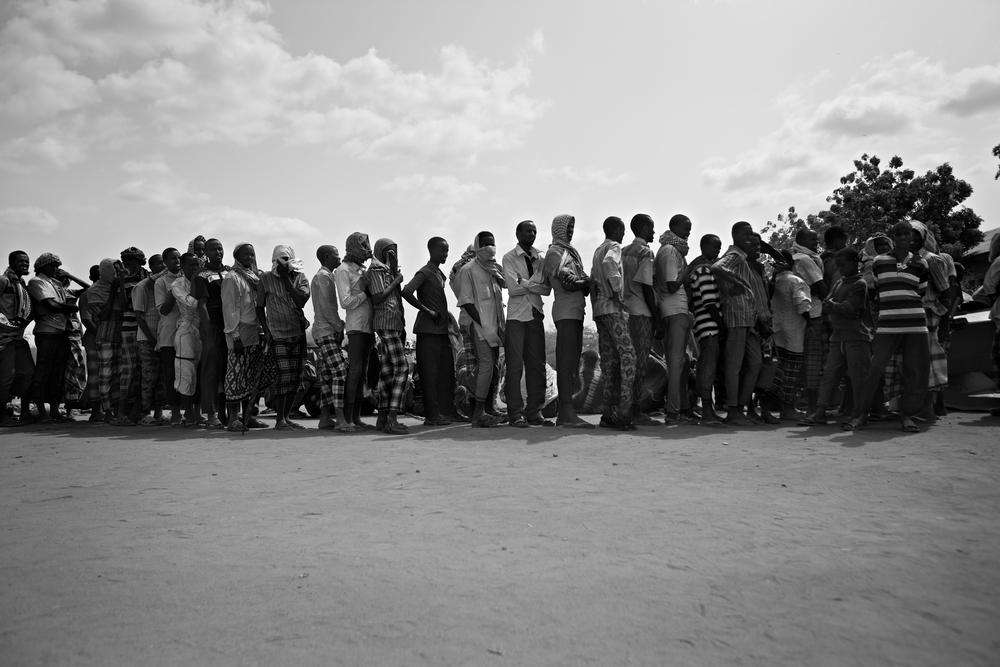

SOMALI REFUGEES IN DADAAB

The sprawling Dadaab camp in Kenya is home to some 350,000 Somali refugees, making it the largest refugee camp in the world. Originally planned more than 20 years ago as a temporary camp, it has only expanded and suffered from lack of funding. Insecurity and violence have plagued the camp inhabitants.

In November 2013, an agreement was signed by the governments of Kenya, Somalia, and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to promote the voluntary repatriation of camp residents as security began to improve in Somalia. Few people chose to return to Somalia, however, because security remained shaky in many places and had actually deteriorated in others. Nonetheless, as the end of the three-year agreement approaches, the government of Kenya has communicated publicly that efforts will accelerate to return Dadaab residents to Somalia for “security, economic, and environmental reasons.”

Despite repeated reports that the camp residents lack sufficient water, food, and shelter, participants in focus group discussions and a household survey conducted by MSF in August 2016 strongly indicated that they would prefer to remain in Dadaab where they feel more secure and have access to basic health services and education. Even though they are unable to live or move freely within the confines of the camp, most said they found Dadaab preferable to the instability, insecurity, and lack of basic amenities in Somalia.

In the New York Declaration, governments declared that refugee camps must be an exception, rather than the rule, for managing refugee flows. While keeping hundreds of thousands of refugees in Dadaab is hardly a long-term solution, forcing them back to Somalia is inhumane and in violation of non-refoulement, a law that forbids refugees or asylum seekers from being forced to return to places where they are in danger.

While it is evident that refugee camps are not ideal for managing prolonged refugee situations, closing them should not place people at greater risk. MSF strongly opposes the Kenyan government’s intention to close Dadaab. Without other feasible solutions, the closure of the camp means that refugees will be forced to return to Somalia, which holds dramatic and life-threatening consequences.

REFUGEES AND MIGRANTS IN LIBYA

Since the launch of search and rescue operations last year in the central Mediterranean Sea, MSF teams have saved more than 34,000 people from drowning and many other life-threatening situations. Regardless of their country of origin or their reasons for transport to European shores, almost everyone rescued in the central Mediterranean passed through Libya.

And almost all of them reported witnessing or experiencing extreme violence against refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants in Libya including beatings, whippings with hoses, sexual violence, and killings. MSF medical teams onboard three rescue vessels in the Mediterranean continue to treat and bear witness to the consequences of physical and psychological violence inflicted on men, women, and growing numbers of unaccompanied children, some as young as 10 years old.

Although it can be difficult to definitively identify mental trauma in the short period rescued people spend on MSF boats, MSF medics have seen countless examples of the abuse and brutality endured on the migratory route through Libya. They’ve seen, to cite a few examples, a man with a week-old infected machete wound on his forearm, a young woman with a perforated eardrum caused by repeated blows to the head, men with severe swelling from beatings to the groin, a man with a broken collarbone and extensive scarring on his back from lashings he received while in detention, and a man with shattered hand bones from being hit repeatedly with a Kalashnikov rifle. Women have reported being raped, forced into prostitution or kept in captivity as domestic servants. They’ve reported unwanted pregnancies, knocked out teeth, and hands burned in fires, among the many acts of abuse.

THE MEDITERRANEAN CROSSING

Already this year, 3,198 people have died attempting to reach Europe. The Central Mediterranean crossing, from Libya to Italy, is almost twice as deadly as it was last year. With seemingly no political will to provide safe and legal alternatives to the deadly sea crossing, the European Union and European government policies continue to eliminate the safest exit routes, leaving people no other choice but to resort to overcrowded boats headed for Europe by inexperienced guides.

While the New York Declaration promises to strengthen search and rescue mechanisms at sea and on land, establishing safe and legal routes is the only way to end deaths at sea. In the meantime, MSF has repeatedly called for a dedicated and proactive search and rescue mechanism to complement efforts put in place by the Italian government in the Central Mediterranean.

RECEPTION AND TRANSIT IN ITALY, GREECE AND THE BALKANS

Two years into the widely identified European Refugee crisis, the situation in many parts of Europe continues to be both chaotic and inhumane. In the six months since the EU-Turkey deal— signed by the 28 EU member states—came into effect, the right to seek asylum within the EU has become dangerously restricted, with thousands of people stuck at borders, denied protection, and living in dire conditions with little hope for the future.

EU member states have approved an effort that violates the principle of non-refoulement by rejecting men, women and children at borders in Bulgaria, Serbia, and Hungary without assessment of their protection needs. These people are then pushed back to inefficient asylum systems in Turkey, Serbia or Greece and forced to live in unsafe conditions.

The progressive closure of the Balkan route through Macedonia, Bulgaria, Slovenia, Croatia, and Hungary has left smugglers as the only option for transit within Europe. The militarization of these countries’ borders has led to a staggering increase in violence. MSF data show that nearly one-in-three patients attending MSF clinics in the Balkans report abuse and violence; this includes women and children. The situation became so acute at the end of August that MSF teams in Serbia were forced to refer some patients to hospitals due to the severity of their wounds. While smugglers are responsible for much of this violence, patients report that at least half is perpetrated by state authorities.

Although the New York Declaration promises to "ensure a people-centered, sensitive, humane, dignified, gender responsive and prompt reception for all persons arriving," the reality is that in all countries, the reception system is failing to adequately provide the necessary care and services for those who have fled their homes.

To wit: More than 13,000 people remain stuck on Greek islands, crammed into spaces meant to house 7,450. The areas lack basic services including health care and water, as well as information and avenues to due process, which is causing tensions to rise.

The mainland is not much better; the conditions in many of the camps are sub-standard and some were built with materials containing harmful substances like asbestos. Around one-quarter of MSF’s patients on mainland Greece exhibit symptoms of depression and anxiety. In Italy, increasing numbers of people are excluded by the formal reception system and live in appalling conditions in squats and makeshift camps where there is also very little access to health care and other basic services.

The New York Declaration promises that "the special needs of all people in vulnerable situations will be recognized." But both Greece and Italy are extremely unprepared to provide appropriate services to vulnerable groups. For example: more than 90 percent of the minors arriving in Italy are unaccompanied—some as young as 10 years old. Not only have these children experienced and witnessed horrific events on their journeys, but once they arrive in Italy, they are often detained or kept in closed reception centers instead of structures that cater to the specific needs of child trauma survivors. The situation is no better in Greece.

Mental health services are rarely provided in Italy and Greece, and both countries lack adapted services for victims of torture or appropriate screening practices to locate the vulnerable. The reception systems in Italy, Greece, and the Balkans also fail to properly provide for survivors of sexual violence and people with disabilities or severe medical conditions.

The MSF team in Serbia, for example, identified a young Afghan woman who had developed breast cancer. After a mastectomy in Greece she was unable to stay to complete her radiation and chemotherapy treatment; she later relapsed in Serbia, where she was living in squalid conditions without anything approaching sufficient medical care, waiting to cross the Hungarian border. Putting people with serious medical cases in this position infringes on their right to health care.

Despite the promises of the New York Declaration and the millions of Euros invested by the EU, people arriving in the European countries where MSF works do not find refuge. They are instead forced to endure more hardship: detention, violence, squalid living conditions, and a lack of access to basic services. European countries are collectively failing those they have promised to protect.

FLEEING VIOLENCE IN THE LAKE CHAD REGION

Some 2.6 million people have been forced to flee their homes in northeast Nigeria due to violent attacks perpetrated by Boko Haram and the military forces combating them. Civilians pay the price of extreme violence and are left with little means to cope and little hope to rebuild their lives.

Some receive assistance in refugee camps while the majority live in precarious conditions in host communities where resources are already limited. Some have sought refuge or have been forcibly moved to locations where they are trapped and entirely reliant on outside assistance. High insecurity in these areas makes the provision of aid difficult, leaving people in dire conditions with unmet basic living and health care needs.

MSF assists the displaced in a number of locations throughout Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad, and Niger, where there is a worryingly high prevalence of epidemics and diseases related to poor living conditions, including waterborne illnesses and very high malnutrition rates.

Violence and displacement exacerbate an already dire situation in a region suffering from poverty, extreme vulnerability, food insecurity, recurring outbreaks and an almost non-existing health system. People affected by the ongoing crisis are in urgent need of food, drinking water, shelter, health care, protection and education.

Today, people are stranded with no certainty that they can go back to their homes or rebuild their lives in an environment where they can raise their children in safety.

VICTIMS OF VIOLENCE AND ASYLUM SEEKERS FROM CENTRAL AMERICA IN MEXICO AND THE U.S.

Every year, an estimated 300,000 people flee violence and poverty in El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala, and enter Mexico hoping to gain asylum in Mexico or transit onwards to the United States.

The violence many of these people have experienced and fled is not unlike that in war zones around the world. Murders, kidnappings, threats, recruitment by non-state armed actors, extortion and forced disappearance are the daily burden of thousands who live in areas controlled by gangs and criminal groups. Sixteen percent of the NTCA patients cared for by MSF teams in Mexico mention direct attacks as the main reason for fleeing their country, while as much as 41 percent decided to leave after receiving individual threats.

Populations from Central America entering illegally into Mexico are systematically exposed to further episodes of violence across the country. According to MSF data, 68 percent of the migrant population cared for by MSF teams reported being victims of violence during their transit toward the United States. One-third of the women had been sexually abused.

The consequences of violence on mental health and the ability to reach out for assistance are striking: 47 percent of the victims report being psychologically affected by the violence they were subjected to or witnessed. A large majority of the migrants [59 percent] affected by violence did not seek any assistance during the transit through Mexico despite self-identified needs, mainly because of fear for their security, retaliation or deportation. There is no doubt that Mexican laws affording the right to health care of every individual in its territory—independent of their administrative status—is not respected in practice.

Programa Frontera Sur [Mexico’s south border strategy], which was implemented in Mexico with the financial support of the United States, exposes victims of violence in Central America to additional dangers and systematically deprives this population of the asylum and protection mechanisms they need. Despite an already existing framework for refugee claims for victims of organized gangs, only 0.5 percent of people fleeing Honduras and El Salvador have been granted asylum status in Mexico. In 2015, the government of Mexico deported 150,000 people from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, a 44 percent spike from the previous year.

The plight of those who reach the United States is equally worrying. Those caught by migration authorities who make an asylum claim are held in detention centers to await asylum hearings before a judge. Very few are granted passage.

Despite legitimate fear for their lives, people from Central America fleeing violence are systematically deported from Mexico and the U.S. to their country of origin in what constitutes a violation of the principle of non-refoulement. Lack of access to healthcare, protection, and humanitarian assistance for the population fleeing violence in Central America must be regarded as a collective failure of the states in the region.

ROHINGYA PEOPLE IN SOUTHEAST ASIA

For years, Rohingya people in Myanmar have had no option but to use smugglers in order to flee persecution. As a stateless minority, there is no other way for them to leave the country, and although departures have fallen following a crackdown on smuggling networks, some continue to try.

In Rakhine state, Rohingya people are subjected to severe movement restrictions, both those living in displacement camps and those living in their own villages, that severely limit their ability to access health care. Outside of displacement camps, MSF is one of their only options to access basic health care.

Many Rohingya people have fled to Bangladesh, where up to half a million are currently living, but most do not have formal refugee status and instead exist in a kind of legal limbo. This makes it extremely difficult for them to access health facilities, support services or protection from exploitation.

In recent years, many Rohingya people have fled from Myanmar and Bangladesh to other countries, especially to Malaysia but also to Indonesia and Thailand. Many Bangladeshis have also followed this route, seeing smugglers’ boats as their only viable option to improve their situation.

When they make it to their desired destinations in the region, Rohingya asylum seekers face considerable difficulties. As these nations are not participants of the Refugee Convention, they have no way of gaining formal legal status as refugees, which in turn affects their ability to access health care and meet other needs, while exposing them to the risk of arrest and detention as well.