International humanitarian organizations and United Nations agencies must scale up their response, and the warring parties must stop obstructing humanitarian aid.

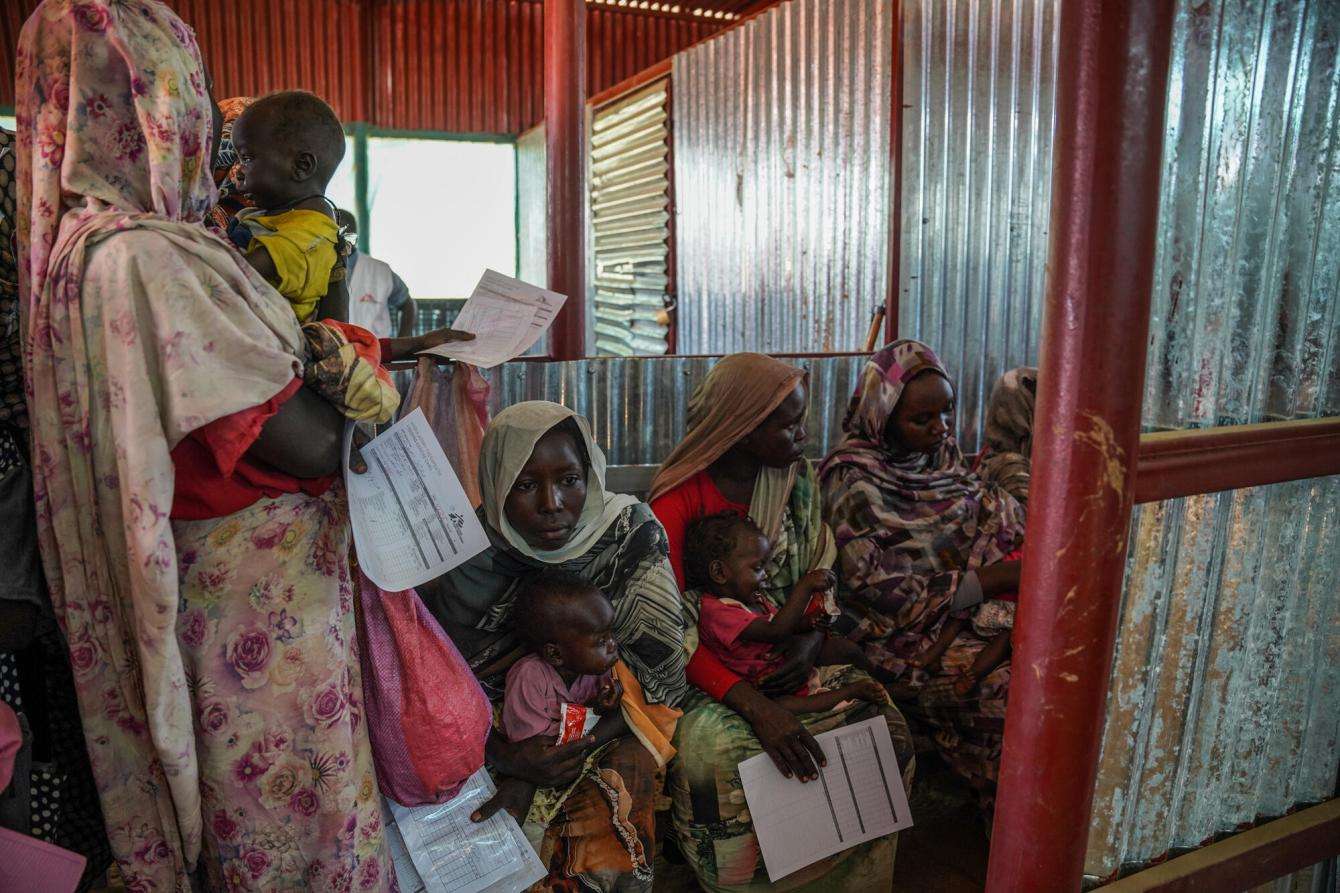

PORT SUDAN, April 12, 2024—Ahead of a key donor conference on Monday in Paris, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is calling urgently on organizations and governments to scale up their response to the vast humanitarian needs caused by war in Sudan and on the warring parties to honor commitments to stop violence against humanitarian workers, stop blocking vital supplies and facilitate access to people in need.

In one of the world's worst crises in decades, Sudan is facing a colossal, man-made catastrophe one year into the ongoing war between the government-led Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF). More than 8 million people have already been forced to flee their homes, and 25 million—half of the country’s population—are estimated to be in need of humanitarian assistance, yet the world is looking away as the warring parties intentionally block humanitarian access and the delivery of aid. The United Nations and member states must redouble their efforts to negotiate safe and unhindered access and scale up the humanitarian response to prevent this already desperate situation from deteriorating any further.

“People in Sudan are suffering immensely as heavy fighting persists—including bombardments, shelling, and ground operations in residential urban areas and in villages—and the health system and basic services have largely collapsed or have been damaged by the warring parties," said Jean Stowell, MSF head of mission in Sudan. "Only 20 to 30 percent of health facilities remain functional in Sudan, meaning that there is extremely limited availability of health care for people across the country."

In areas close to hostilities, MSF teams treat women, men, and children who are directly wounded in the fighting and crossfire, including shrapnel, blast, and gunshot injuries. Since April 2023, MSF-supported facilities have received more than 22,800 patients with traumatic injuries and performed more than 4,600 surgeries, largely due to violence in Khartoum and Darfur. In Wad Madani, a city surrounded by active front lines, we see currently 200 patients per month with violence-related injuries.

One year of war in Sudan

View the timeline“Every day we see patients dying because of violence-related injuries, children perishing due to malnutrition and the lack of vaccines, women with complications after unsafe deliveries, patients who have experienced sexual violence, and people with chronic diseases who cannot access their medicines,” Stowell said. “Despite all this, there is an extremely disturbing humanitarian void.”

Although MSF works in good cooperation with the Ministry of Health, the Government of Sudan has persistently and deliberately obstructed access to humanitarian aid, especially in areas outside of their control. It has systematically denied travel permits for humanitarian staff and supplies to cross the front lines, restricted the use of border crossings, and established a highly restrictive process for obtaining humanitarian visas.

MSF medical staff in Khartoum report that their biggest challenge is the scarcity of medical supplies, including for surgery, putting doctors on the brink of stopping all activities unless supplies arrive. Khartoum has been under a blockade for the past six months, and the city of Wad Madani has faced a similar situation since January.

In RSF-controlled areas, where many different militias and armed groups also operate, health facilities and warehouses were frequently looted in the first months of the conflict. Incidents such as carjackings continue on a regular basis and medical workers, particularly from the Ministry of Health, have been harassed and arrested.

In hard-to-reach areas like Darfur, Khartoum, or Al Jazirah, there are few international humanitarian organizations present, and MSF is sometimes the only one, while the needs far exceed MSF's capacity to respond. Even in more accessible areas such as White Nile, Blue Nile, Kassala, and Gedaref states, the overall response is negligible: a drop in the ocean.

One example is the catastrophic malnutrition crisis in Zamzam camp in North Darfur, where there have been no food distributions from the World Food Program since May 2023. In January 2024, an MSF team found extremely high rates of malnutrition among children and pregnant and breastfeeding women and a mortality rate of 2.5 per 10,000 people per day across the camp, which is beyond the threshold of a humanitarian emergency.

“The situation in Sudan was already very fragile before the war and it has now become catastrophic," said Ozan Agbas, MSF emergency operations manager for Sudan. "In many of the areas where MSF has started emergency activities, we have not seen the return of the international humanitarian organizations that initially evacuated in April 2023. The United Nations and their partners have persisted in self-imposed restrictions on accessing these regions and, as a result, they have not even pre-positioned themselves to intervene or establish teams on the ground when opportunities arise."

Factbox: MSF medical figures at glance

MSF currently works in and supports more than 30 health facilities in 10 states in Sudan: Khartoum, Al Jazirah, White and Blue Nile, Al Gedaref, West Darfur, North, South and Central Darfur, and Red Sea. Our teams have also recently intervened in Kassala. We run activities in both SAF- and RSF-controlled areas. We provide trauma care, maternal care and treat malnutrition alongside other healthcare services.

The needs across the country are massive and largely unmet. Below are just a few medical indicators that illustrate what MSF sees in some of the areas we are able to access and respond in. But we know that this is just the tip of the iceberg.

- Since April 2023, more than half a million people have sought medical consultations at our supported hospitals, health facilities and mobile clinics.

- In hotspots of violence, atrocities have been committed, and civilians have been ethnically targeted and killed: In June, over 1,500 war-wounded Sudanese were received in the MSF-supported hospital in Adré (Chad) in one week. A retrospective mortality survey carried out among refugees confirmed reports of mass killings in West Darfur.

- Between July and December 2023, 135 of the patients who presented to an MSF medical facility in eastern Chad disclosed that they were survivors of rape. All are women or girls between 14 and 40 years old, and most were attacked before their arrival in Chad. The attackers were armed in 90 percent of cases, and 40 percent of the survivors were raped by multiple attackers.

- The indirect health consequences of the war have been equally devastating. Between 70 and 80 percent of hospitals in conflict-affected areas are no longer functioning. Many people have to travel long distances, often amid extreme insecurity, to seek medical care. Patients often arrive late to the health facilities.

- The combination of poor living conditions, lack of access to clean water, lack of vaccinations, and lack of access to health care have significantly combined to create conditions for outbreaks, as happened over the last year, and exacerbated the prevalence of diseases significantly. MSF teams have seen over 100,000 malaria cases, treated more than 2,000 people for cholera and seen many thousands of measles cases.

- Pregnant women are particularly affected by the lack of access to health care. Over the past year, MSF has assisted more than 8,400 deliveries and performed 1,600 cesarean sections.

- Another growing issue is malnutrition. MSF has supported treatment for over 30,000 children with acute malnutrition in a year.

- MSF is also responding in Chad and South Sudan where over a million people have taken refuge since the start of the war in Sudan. The needs of the refugees and returnees there are also immense and not sufficiently addressed. In Chad, for instance, there is currently a hepatitis E outbreak.