In early February 2022 violent clashes erupted in and around Agok, in the Abyei special administrative area of South Sudan, and an estimated 70,000 people were displaced.

While the majority fled to the town of Abyei, others sought refuge in areas further south, with more than 20,400 people registered in Twic County in Warrap state as of March 2022.

In a region that was already vulnerable and prone to recurrent disease outbreaks, the influx of displaced people placed an additional burden on fragile communities. The situation has further worsened by heavy floods, and the area recently experienced another wave of violence.

“In January 2024 alone, we received more than 100 casualties, mainly gunshot wounded patients in need of surgery, and we have activated our mass casualty response plan multiple times,” said Zélie Antier, a project coordinator with MSF in Abyei, South Sudan. “As a consequence, we've upgraded our surgical capacity to be able to respond to the medical needs of the population.”

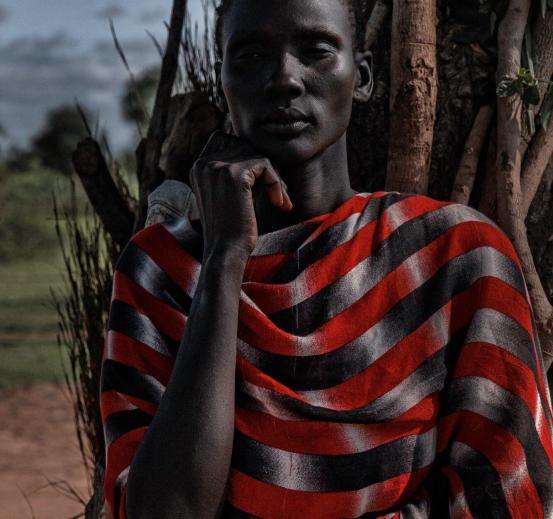

Displaced person

Aweak Deng

“There are security problems in the area. In the camp, people come at night to attack and rob.”

Today, in Abyei and Twic, MSF is providing comprehensive care in four facilities and supports integrated community case management sites in the camps for displaced people. There remains, however, a critical lack of hospital care available in the area; there is no operating theater in the whole of Twic County, leaving patients in need of surgical care at risk.

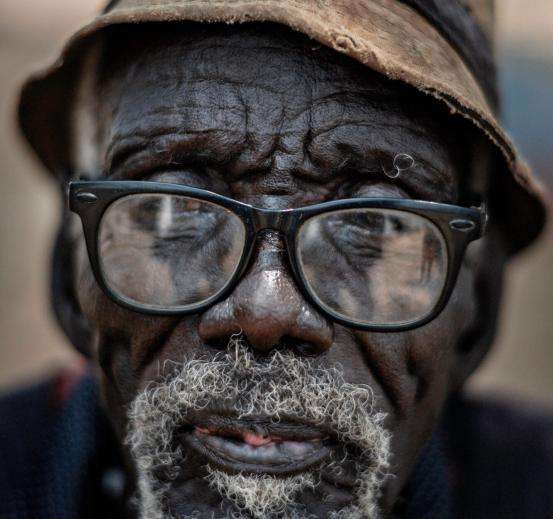

Displaced person

Akol Agok

“We are struggling to get enough food. People are foraging for vegetables and leaves. They are eating things that they never ate before. We don’t know if it will harm us or not. We have no choice.”

Decreased funding and overstretched services

“The main threat in 2024 is the decrease in funding for South Sudan, which has led to a significant decrease in the presence and response of [humanitarian] actors, with major concerns about lack of food and poor water and sanitation conditions—in the camps as well as in most host communities—and poor shelter conditions to [accommodate] the coming rainy season, with limited access to quality health care services,” said Nicolas Guiral, MSF project coordinator in Twic.

This renewed violence has led to deaths, serious injuries, destruction of property and livelihoods, and further displacement. These conditions have stretched our teams and equipment and, during the clashes, MSF lost two team members who, although off-duty and not targeted as staff, became victims of the violence.

“In Twic the recent violence has mainly affected our activities [in] receiving [people who are] wounded or killed,” explained Guiral. “It’s also affecting an important part of our team since most have family members who are from other communities and have been separated until now from the conflict.”

The magnitude of the crisis exceeds the capacity of any single entity, and a collaborative approach is essential for creating a more substantial and effective humanitarian response.

Challenges faced by refugees and returnees from Sudan

Amidst the already dire situation in Abyei, a new challenge has arisen: an influx of returnees and refugees fleeing the horrors of Sudan's ongoing war that began in April 2023. There has been a significant influx of internally displaced people and refugees into South Sudan since the fighting started. Families who had been displaced from their homes sought refuge in Abyei, hoping for safety and a chance to rebuild their shattered lives.

“Most people fled from Agok, north of here,” said a community leader. “Some have come recently from Sudan, and they are still coming every day. More than 6,000 people are living in the camp. When there is peace and MSF goes back to Agok then we will go too. But if there is peace and MSF doesn’t go back, then we won’t go back either. We need MSF. Some [of the people arriving from Sudan] come by official routes and have vouchers and a pass to get food and shelter, but many come on unofficial routes from different directions and they don’t have the necessary papers, so they get no help at all. This is a big problem, and it is growing.”

As of November 2023, more than 400,000 people, predominantly South Sudanese returnees, as well as refugees have crossed the border. The large number of arrivals, particularly women and children, presents challenges for transit sites. Rising market prices have contributed to worsening food insecurity. These add to the challenges South Sudan already faces, such as regular disease outbreaks, flooding, displacement, and high rates of malnutrition.

While MSF continues to provide health care and hospital services, there is an urgent need for additional support from other humanitarian actors in terms of food, water, sanitation, and shelter, especially with the impending seasons of floods as well as violent events that could cause the situation to deteriorate further. In the past year alone, our teams supported 50,000 people and conducted 23,000 emergency consultations.