Muntaha was 28 years old when she left her children in the rural district of Kichicho, in Ethiopia’s Amhara region. A single mother of four, she had been unable to find work in her community and could no longer feed her family. Her friends, who also had few job prospects, told her that a good salary could be earned in Saudi Arabia, and she watched them, one after another, embark on the journey north to find work.

Soon, Muntaha decided that migrating to a Gulf country like her friends was the only way to gain stability for her family. “My plan was to work there for a short time, to earn enough money to open a shop back home so I could feed my children more easily,” she said. “If I had known what would happen, I would never have left to begin with.”

A dangerous passage by land and sea

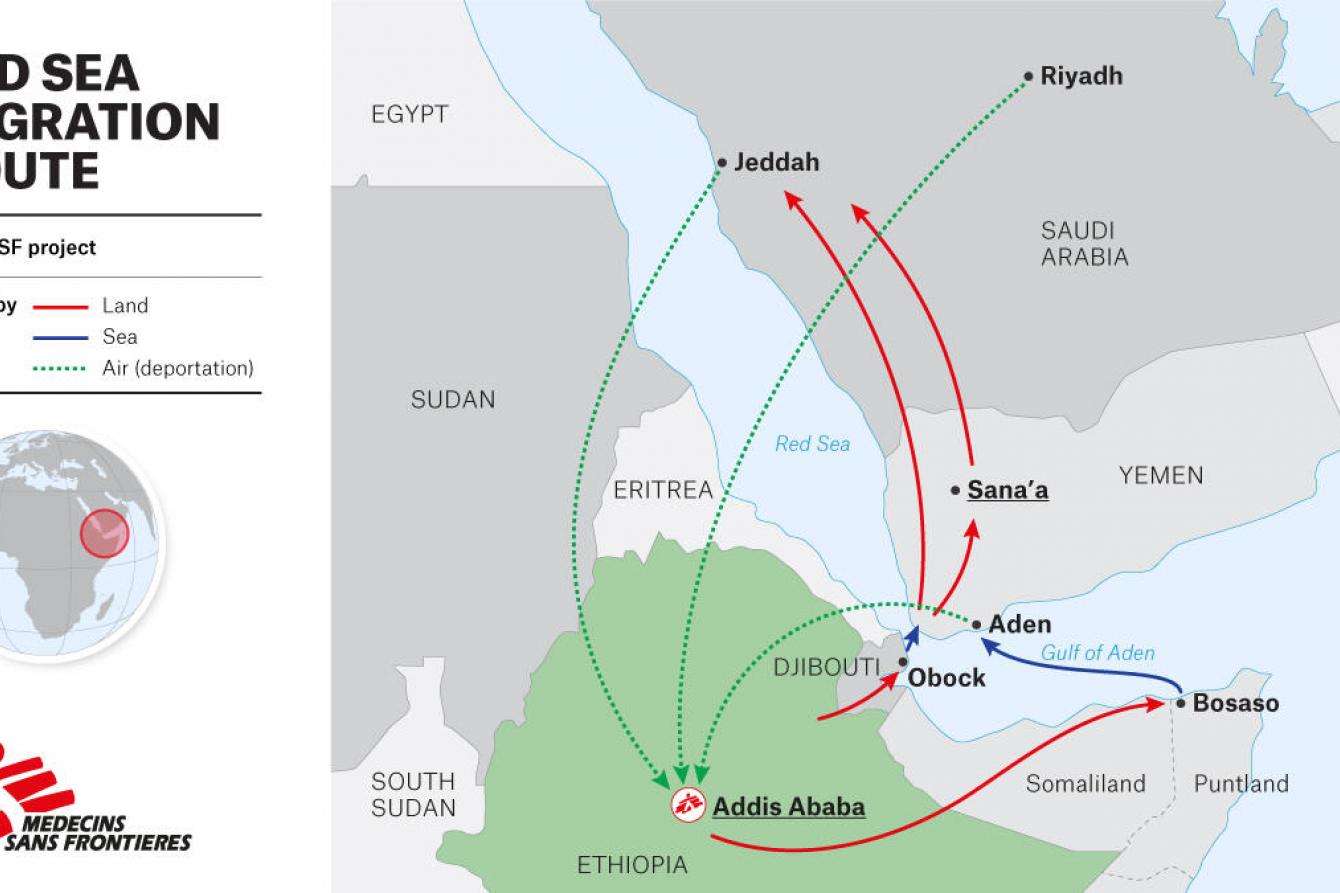

Muntaha’s story is similar to those of thousands of Ethiopians who migrate to Saudi Arabia or other Gulf countries each year with the false hope of finding work for fair pay. While relatively unknown internationally, the migration route from the Horn of Africa through Yemen is one of the busiest in the world. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, around 12,000 people started on this dangerous passage every month. Most, like Muntaha, come from rural areas of Ethiopia’s Tigray, Amhara, and Oromia regions.

Typically, they pass through Djibouti or Somaliland by foot, then cross the Red Sea, arriving on the coast of Yemen. They walk through Yemen, a country that has been convulsed by war for the last six years, to try to reach the border of Saudi Arabia.

At countless points on the route, smugglers and traffickers wait to entrap migrants by offering guided passage in exchange for hefty payments. “Both choices are dangerous,” Muntaha said. “If you say you will go with them, you will face rape and other mistreatment. But if you refuse, they will beat you or rape you.”

Muntaha was determined to elude traffickers and make the journey on her own, but ultimately it was impossible. “I tried to escape from them until I reached the shore in Yemen,” she said. “But I couldn’t. So finally, I went with one of them.”

Little did she know that she would be handed over to several more traffickers before her journey was over. Each one repeatedly demanded her family’s phone number so they could extract money from her relatives. When she refused to give it to them, they beat her. In Yemen, she was abused by traffickers for a month before she was allowed to walk to Saudi Arabia. “People die trying to cross to Saudi,” she said. “I passed many dead bodies along the way.”

Those who do make it to Saudi Arabia often continue to face violence and mistreatment. Since 2017, Saudi Arabia has been arresting undocumented migrants and detaining them in overcrowded, unhygienic conditions before deporting them back to their countries of origin. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Saudi authorities deported around 10,000 Ethiopians each month.

A worsening crisis

In 2020, the pandemic only compounded the trauma that migrants face. Despite a drop in migration due to closed borders, at least 37,535 migrants arrived in Yemen that year. According to reports from migrants sent back to Ethiopia, conditions along the route have gotten worse. Migrants face an even higher risk of violence, or find themselves stranded in unsafe situations without access to basic services, including health care.

While mass deportations were suspended for most of 2020, detention continued in Yemen and Saudi Arabia, resulting in migrants being held for extended periods of time. In the first quarter of 2021, more than 60 percent of Ethiopian returnees from Saudi Arabia evaluated by Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) had spent six months to a year in detention, a dramatic increase from 2019 when the average was less than three months.

Muntaha was injured during her arrest in Saudi Arabia and taken to a detention center with a fractured skull and a wounded leg. “I was held there for seven months,” she said. “I kept asking them to take me to the hospital to change the dressings on my wounds, but no one would talk to me.”

These traumatic experiences take a heavy toll. MSF teams see people return to Ethiopia in a worse state than those who came back in previous years, with significant medical and mental health needs. In the first three months of 2021, we provided 3,457 medical consultations and 832 individual mental health consultations to new returnees. Teams identified 380 patients with psychiatric symptoms in just three months—more than all the cases identified in 2019 and 2020 combined. The most common medical conditions MSF has seen are those associated with overcrowded living conditions and lack of access to medical care, including skin diseases and respiratory infections.

“We are concerned about the poor conditions that undocumented migrants face in detention,” said Himedan Mohammed, MSF head of mission in Ethiopia. “People should not be detained; it should be an exceptional measure of last resort for the shortest period possible—and only if justified by a legitimate purpose.” Where migrants are detained, Mohammed said, “authorities in Ethiopia, Saudi Arabia, and other governments in the region need to ensure their safety and dignified treatment.”

Providing care to restore hope

Mass deportations resumed in October 2020 and are expected to continue increasing. Well over 10,000 Ethiopians were deported from Saudi Arabia in the first quarter of 2021 alone. Muntaha was sent back just a few weeks ago. Like most returnees, she arrived at a special area at Bole International Airport in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital, with no possessions and very little support to start a new life.

MSF teams have been working at this arrival point since March 2018, screening returnees for medical needs and referring severe cases to area hospitals. Since October 2020, MSF has also been working in several transit shelters where returning migrants are transferred for a few days before being sent to their home regions. MSF outreach teams visit these shelters regularly to provide medical and mental health care during their stay.

While the Ethiopian government has made significant efforts to improve reception conditions for returning migrants, challenges and gaps remain. Shelter capacity for new arrivals is limited. Reception facilities are overcrowded and there are inadequate measures in place to reduce the spread of communicable diseases, including COVID-19. And, because most migrants pass quickly in and out of reception centers, there often isn’t enough time to get them the care and services they need. If the number of arrivals increases as expected throughout 2021, these gaps will only grow.

Upon arrival at the airport, returnees with mild to moderate mental health issues are referred to MSF’s therapeutic counseling center (TCC) in Addis Ababa. Depending on their needs, they might spend a few days or up to a month or more at the center where they receive food, clothes, shelter, and assistance for transportation until they are ready to go home.

MSF physicians also treat injuries and other medical needs. In individual and group therapy sessions, our psychologists provide counseling and empower patients with coping strategies to help them overcome common mental health issues, like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, and insomnia. Simple activities like playing games, drawing, doing laundry, and having lunch together help patients reestablish a sense of normalcy and dignity.

Now 30 years old, Muntaha is one of 15 patients currently being treated at the TCC. She is finally receiving follow-up medical treatment for the injuries she sustained in Saudi Arabia. And, through group and private sessions with MSF psychologists, she has started processing what she’s experienced and learning how to manage her ongoing mental health symptoms.

Very soon, she will be ready to return to her home region. When patients are ready to leave the TCC, MSF connects them with services in their area, and TCC staff continue to follow up with them remotely. “Now, I just miss my children,” said Muntaha. “So I want to go to them.”

An uncertain future

For other returnees, the prospect of returning home can come with a host of new fears and challenges. There can be shame and even stigma in returning empty-handed after migrating to earn money for one’s family. Some returnees have caused their families to go deeper into debt to pay traffickers along the route, putting their loved ones in an even worse financial situation. Beyond the pressures of unmet expectations, some deportees return home with mental health conditions that require ongoing care, a reality that some families and communities struggle to accept.

Support services for reintegration are limited at best and non-existent in many areas. Ensuring continuity of medical and mental health care is also a significant challenge. There is little to no access to mental health services, including psychiatric care, outside of Addis Ababa, especially in remote areas of Ethiopia. Therefore, after patients are discharged, they face a high risk of relapsing.

Lack of follow-up, especially for returnees with specific medical and social needs, not only compromises access to vital health services and reintegration into the community, it also increases their risk of repeat migration abroad. Many returnees decide they have no choice but to try the journey again and re-expose themselves to the same traumas.

For these reasons, MSF will soon expand its existing follow-up services for patients after they return home. The team at the TCC has already started accompanying particularly vulnerable patients back to their communities, helping to improve acceptance, ensure continued medical care, and facilitate their reintegration. TCC staff have seen first-hand the difference it makes when returnees receive support and resources, both upon arrival and during their uncertain transition home. For many, it can be the deciding factor in whether they repeat this traumatic cycle of migration, detention, and deportation.