A high level of chronic violence has continued this year across Haiti's capital, Port-au-Prince, creating a need for medical care beyond what patients can afford.

Chronic violence is affecting people in myriad ways across Haiti's capital, Port-au-Prince, as gangs fight for territory and influence amid a larger political and economic crisis in the country. In response to increasing medical needs caused by violence as well as traffic accidents, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) reopened its former trauma hospital in the city's Tabarre neighborhood in November 2019 and has continued to operate it since then.

2020 has been a very difficult year for patients in need of specialized care in Haiti. While Haiti's public health system faces a chronic lack of resources, this year it has also seen repeated strikes and staffing shortages due to violence against health workers, low or unpaid wages, and the risks of COVID-19.

MSF teams have treated more than 1,795 trauma patients in the Tabarre hospital since November 2019, from the emergency room to surgery, psychosocial care, and physiotherapy. The hospital's six-bed intensive care unit is often full, and sometimes over capacity.

MSF provides all care free-of-charge, based on medical needs alone, but the medical criteria are specific: patients are admitted through the emergency room with life-threatening injuries, such as open bone fractures of the limbs or severe wounds to the chest or abdomen.

Yet those who are admitted represent only 28 percent of all the patients who seek care at Tabarre for traumatic injuries or other conditions. Patients often arrive with injuries that are not life-threatening, such as closed bone fractures or lacerations, describing how difficult it is to find care, especially care they can afford.

"Most of these patients don't have the ability to pay and there are not a lot of options for where to refer them," said Dr. Naina Bhalla, the head of the medical team at MSF's Tabarre hospital. "There are often difficult discussions with a patient and their family about where to refer them—it's not just based on the medical needs, but what they can pay for."

Chronic violence increases medical needs

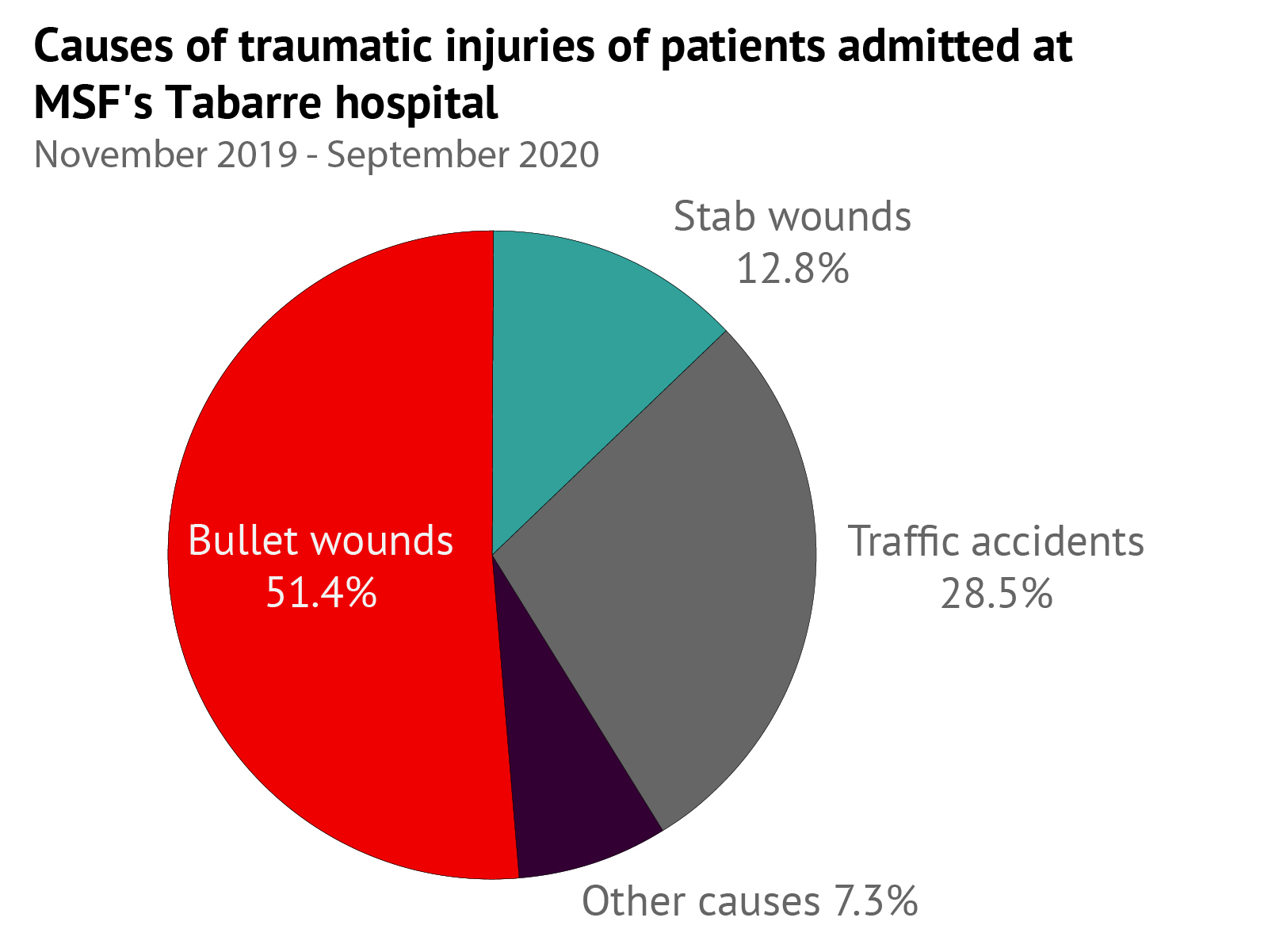

Most of the trauma patients who are admitted to the Tabarre hospital come from neighborhoods across Port-au-Prince, and a few arrive from other regions of Haiti. Approximately two-thirds have suffered gunshot or stabbing wounds, while nearly a third were injured in traffic accidents.

Patients and staff describe a daily reality of violence in the city that could affect anyone. Philippe [name changed], a 26-year-old patient, gave the following account in November 2020:

It was around 9 p.m. when I left my job, jumped on a motorcycle taxi and headed home. Then some armed men wanted the taxi to stop but the taxi men refused, so they started shooting. The driver was killed and I was just behind him and got shot too. I went to a public hospital but they had no supplies in order to take care of me and asked me to buy them myself. I had no money. The next morning I came to Tabarre. I had surgery and a few days later the psychologist came to my room. He told me that my leg was in an extremely bad state and that it would most probably need amputation. I was in shock. I’m the only provider for my family and I have four children. It took a lot of courage to accept it.

Similar stories are all too common, according to MSF's patients and staff. "Haiti is one of the poorest countries of this hemisphere," explains Elkins Voltaire, Tabarre hospital psychologist. ”We have long had armed groups and gangs, especially from 2004 onward, but in the past few years this increased with a multitude of armed robberies and violent conflicts. Access to health care is low because people have no means to access it. There are very highly qualified staff working in public hospitals but they are not always paid, they are sometimes on strike, and patients are forced to pay for the supplies in order to get treatment."

Trauma care during a pandemic

The arrival of COVID-19 in Haiti in 2020 also limited patients' options for accessing trauma care, among other kinds of specialized care. A public hospital intended to serve as a 40-bed trauma center in Port-au-Prince, Delmas 2, was instead designated as a treatment center for COVID-19.

While disruptions from COVID-19 affected MSF's Tabarre hospital as well, creating staffing and supply difficulties for several months, it has remained open throughout 2020, admitting nearly 150 patients per month on average. Most arrive directly to the emergency room, often in brightly colored Tap Tap taxis, while others are brought by ambulance from MSF's emergency center in the Martissant neighborhood. The challenges begin immediately as patients with stabbing or gunshot wounds or broken limbs are stabilized, then admitted for emergency surgeries.

"We receive very complex cases in need of urgent trauma care," says Vladimir Romelus, an MSF orthopedic surgeon. "It is a lifesaving project, and many of these patients would die if they did not receive this care. One of the hardest things is when we need to do an amputation when there is nothing left to do to save a limb. It is a personal trauma that patients have to absorb when they are amputated. I will never forget a child of about 11 years old who had been hit by a car. When he came in the surgery room, one of his legs could not be saved. We tried really hard to save the other leg and we did manage in the end. But it was not easy."

Blood saves lives

Patients with life-threatening traumatic injuries often need substantial transfusions of blood to undergo surgery. Since November 2019, donors have contributed more than 870 bags of blood for surgical patients at Tabarre (each bag holds 450 milliliters), yet the needs continue to grow. Compatible blood must be donated, often by a family member, and then screened.

"Blood is truly vital to allow this lifesaving work to continue," Bhalla explains. "Any shortage can put our patients at risk, so the blood supply really needs to be maintained in Port-au-Prince."

Recovering from injuries: “Life doesn’t stop here”

Patients stay at the Tabarre hospital for about a week on average, yet some may stay far longer if needed. Recovery and rehabilitation can require months of follow-up care, from dressing changes to physiotherapy. As patients continue to be admitted and then discharged into outpatient care, activities in the outpatient department have grown dramatically.

"At the beginning we started by having 10 patients per day in the outpatient department," says Roussena Rouzard, outpatient head nurse. "As of November 2020, we are caring for more than 670 patients in the outpatient department. We see approximately 50 patients per day and some days we even reach 80. Unfortunately due to the security situation in the city and the country we have patients that don’t come to their follow-up appointments for up to two months. So people come from the countryside which makes it challenging for them to reach Tabarre. But if they come late the risk for their wounds to be infected is increased."

Physiotherapy can be a long process, over many months. Patients who have undergone amputations may be fitted with a prosthetic limb and undergo 10 or more sessions to become comfortable with it. Many patients must strengthen damaged muscles and find ways to adapt to new challenges.

Philippe, the 26-year-old patient who underwent a leg amputation, awaits a prosthetic limb while his leg heals more fully. He laments the profound toll that violence has taken, not only on his body, but on his family.

"The psychologist told me 'life doesn’t stop here,'" Philippe says. "It was hard to accept my new self and how would my wife or my children accept this new image of me? ... Since I’m at Tabarre my oldest daughter, 7 years old, had to drop out of school because I earned no money to continue paying her tuition. They shot me, made me disabled and blocked the education and a better future I could provide to my children."