For people living in Mathare, one of the largest slums in Nairobi, Kenya, the disruption to local health services caused by a curfew and other preventative measures implemented as a part of the country’s COVID-19 response may prove more dangerous to the 500,000 people living there than the outbreak itself. Shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) for health care workers are exacerbating the problem.

As of May 14, there were 758 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 42 deaths in Kenya, and although this number is relatively low, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) teams working in Mathare have already witnessed the impacts of the outbreak response on people’s access to health care.

“Many private health facilities closed because of the risk of contamination and the lack of PPE,” says Dr. Hajir Elyas, MSF project coordinator in Mathare. “At least one public health center has been closed and its staff quarantined after some of them tested positive [for COVID-19]. Some hospitals are refusing to admit patients with respiratory issues even when coronavirus has been ruled out. As a consequence, many [people with] tuberculosis, asthma, and pneumonia end up in COVID-19 isolation facilities, resulting in delayed care and increased exposure to [the virus].”

As in many other MSF projects, our teams in Mathare have adapted and expanded programs to fill gaps and continue providing emergency medical services and medical and psychological care for victims of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) amid the pandemic. But our supplies of PPE are limited, and if a reliable source is not found soon MSF may have no choice but to suspend lifesaving activities. Doing so in the middle of an outbreak will be catastrophic.

Consequences of a curfew

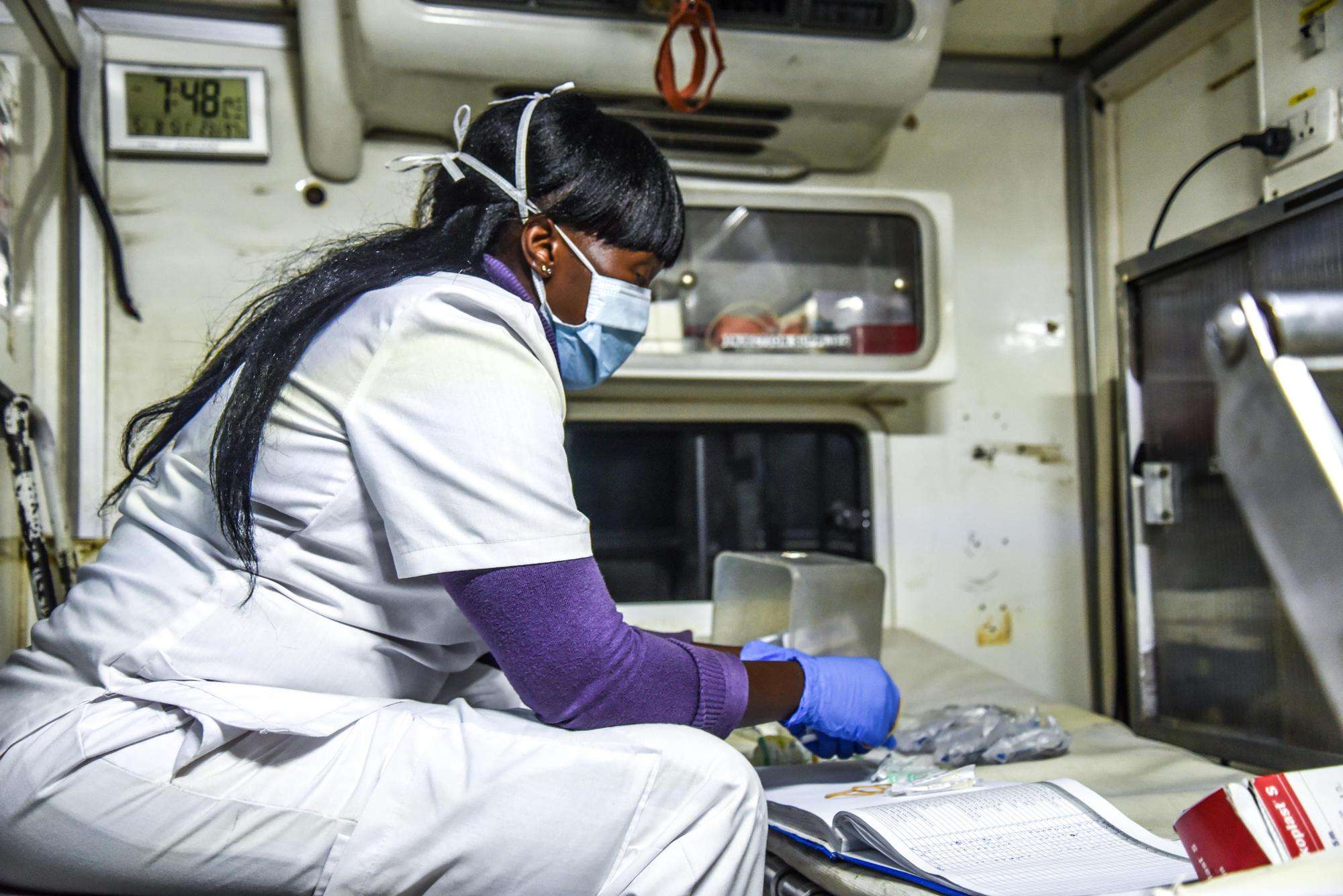

In April, MSF teams received 551 ambulance calls and 2,300 people at the emergency room—more than any other month this year. The number of obstetric patients calling MSF’s ambulance at night more than doubled from 98 in March to 209 in April, due to a curfew implemented as part of the pandemic response, a lack of transportation options, and some health facilities not accepting patients.

“The challenge for pregnant women is that no taxis or public service vehicles are operating after curfew, not even the boda boda (motorcycle taxis) that people use in informal settlements,” said George Wambugu, MSF’s medical activities manager. “This leaves mothers exposed to obstetric complications. We’ve had mothers deliver in our ambulances or in the trauma room. We recently had a mother deliver a pre-term baby in need of resuscitation in our ambulance. Luckily, the baby survived, and both recovered well.”

Trapped at home

Victims of sexual violence are facing a particularly difficult situation made worse by the lack of transportation options. Despite reports of increases in sexual violence, the number of women coming to MSF’s center dedicated to care for victims of SGBV, known as the “Lavender House” because of its purple façade, has decreased.

“We know the number of cases is on the rise,” said Dr. Elyas. “We received calls from women or [children] trapped with their abusers, with no way to leave and access care.”

In Mathare, many people live in cramped conditions where physical distancing to prevent transmission of the coronavirus is impossible. Many also lack access to clean water, making proper hygiene and handwashing difficult. People also need to earn a living, so “staying home” is not viable.

Increasing needs, decreasing access

As the rainy season approaches, the seasonal increase in respiratory disease is expected to add an additional challenge. “People with respiratory symptoms, particularly children, may be labeled as suspected COVID-19 cases and referred to the wrong hospital, resulting in late or inappropriate care,” said Dr. Elyas. “As a consequence, we can expect some reluctance by parents to bring the children to health facilities.”

While the number of reported COVID-19 cases in Kenya has remained relatively low, they are expected to increase, and with that so will the number of victims indirectly harmed by the outbreak: Those who cannot access essential medical care for other illnesses.