Since late 2019, Lebanon has been grappling with its worst economic crisis in decades, social unrest, and political turmoil. To make matters worse, as COVID-19 cases surged across the country last year, a major explosion rocked Beirut, the country’s capital, in August. These overlapping crises have made people already living in precarious conditions even more vulnerable, including more than 1.5 million refugees, the most per capita of any country in the world.

“This situation has compounded the needs of the population,” said Dr. Caline Rehayem, deputy medical coordinator for Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in Lebanon. “The socioeconomic pressure, above all, has made the cost of basic goods, including food, more and more difficult to afford for many. “Medical fees have also become prohibitive for vulnerable groups in the country. This context is expected to worsen people’s health conditions and access to care, and our teams on the ground have already started to witness signs of deterioration.”

Deepening poverty

According to the UN, more than half of people who live in Lebanon are trapped in poverty—almost double the rate of last year. For refugees in the country, the numbers are even more staggering. Approximately 89 percent of Syrians live below the extreme poverty line. This means they live with less than 10,000 Lebanese pounds per person per day—the equivalent of just $6.50 based on the current official dollar rate set by the central bank.

Lebanon’s highly privatized health care system was already a significant barrier for the country’s most vulnerable people, who struggled to access affordable care. The annual inflation rate, which surged to 133 percent in November 2020, impacted both Lebanese people and refugees in the country—directly limiting their ability to access health care.

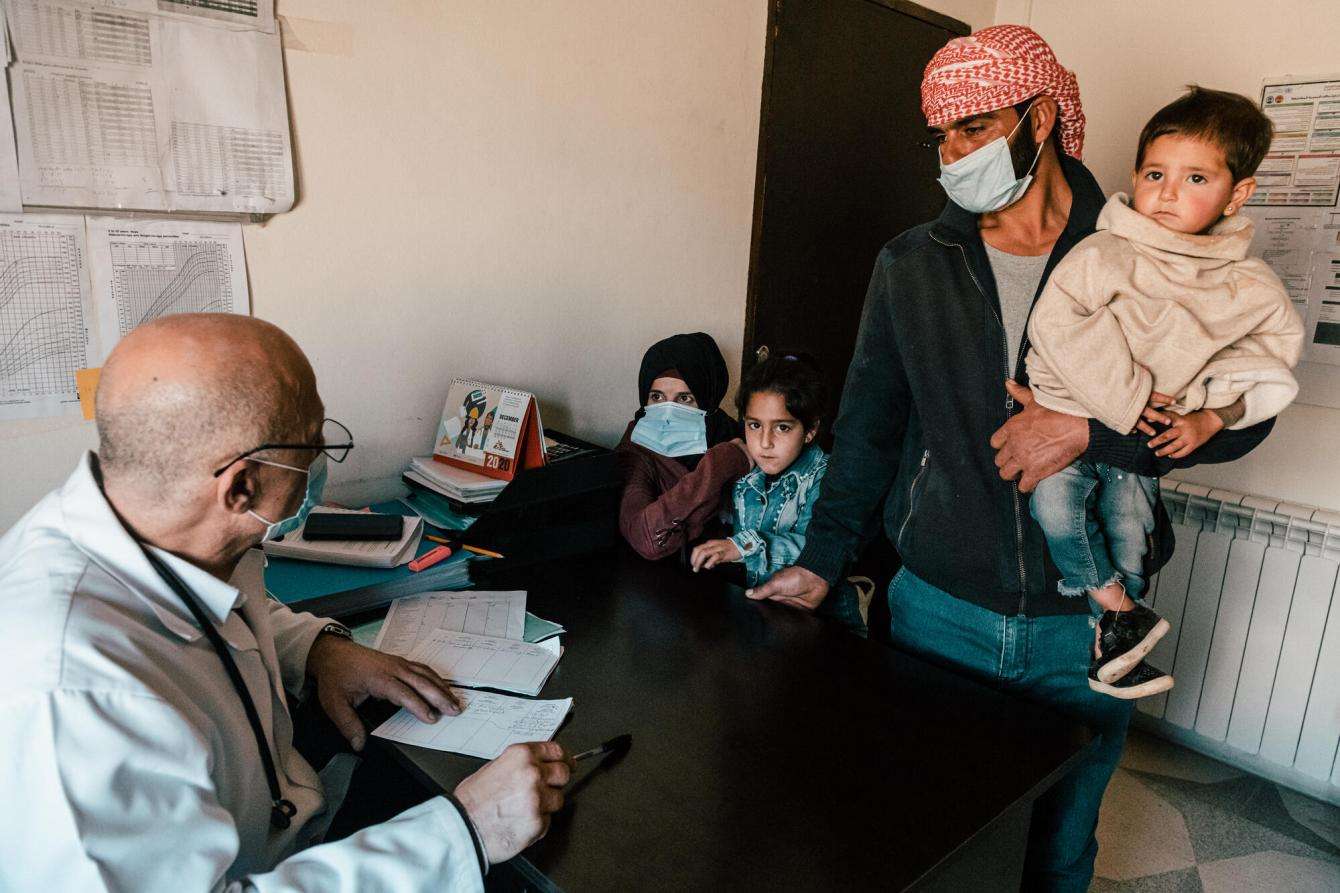

With care at private clinics out of reach for so many, a growing number of Lebanese people have been visiting MSF clinics over the past year, especially in remote areas. In our clinic in Hermel, in the northern part of the Bekaa Valley, the number of Lebanese patients with non-communicable diseases requesting our free services more than doubled between 2019 and 2020. In Arsal, another town in Bekaa Valley, the number of pediatric consultations at our clinic increased 100 percent in the span of a year.

“Two months ago, my husband lost his job,” said Fatima, a 58-year-old Lebanese woman living in Hermel, who has diabetes and suffers from severe complications. “We have always been poor but at least before we were able to cope. We eat mostly lentils, bulgur, and potatoes—a lot of potatoes. It’s not a very good diet for my medical condition, but that’s all we can afford. Without MSF, I’d have to rely on people’s charity to get my medicines.”

Patients living with diabetes are advised to follow diets to help control their blood sugar levels and reduce the risks of developing complications. But in MSF clinics across the country, patients are reporting that the financial struggle to access basic food items, such as meat and even some vegetables, has become a daily reality.

Ahmed is a Syrian refugee who lives in an informal tented settlement in the outskirts of Arsal. Four months ago, his youngest daughter, Zeinab, was diagnosed with anemia. “She looked very sick. She was very pale and ate very little,” he said. “The doctor prescribed her an iron supplement and advised us to feed her more vegetables and beans, since we can no longer afford meat. Everything has become at least four times more expensive and it’s only getting worse.”

Crisis upon crisis

Lebanon’s public health system, which already faced regular medicine and medical supply shortages, has been stressed further by the COVID-19 pandemic and weakened by the August explosion in Beirut, which destroyed important infrastructure including several hospitals, in addition to leaving thousands of people wounded and displaced.

In September 2020, as part of MSF’s post-blast emergency response, our teams carried out a survey of a random sample of 253 of our patients with noncommunicable diseases. The results showed that 29 percent of them had already interrupted or rationed their medication before the explosion. Almost half of those patients mentioned financial difficulties as the main reason; while 11 percent said it was due to medicine shortages.

“When I go to the health center, they often tell me there’s no medication available,” said Mariam, a Lebanese mother of eight who lives in Abdeh, in the north of the country. “The pharmacies regularly run out of drugs too.” Mariam suffers from chronic diseases including diabetes and cardiovascular problems. Her youngest son has asthma.

“I get anxious thinking about what would happen if I couldn’t work anymore,” she said. “How could I afford all the medications? I’d have to choose between the drugs for my son and the ones for me.”

Since the explosion, the public health system has also struggled to cope with the growing number of COVID-19 cases, which rose from less than 200 cases a day before the blast to an average of 1,500 in December 2020. To date, more than 226,000 cases have been reported nationwide.

In August 2020, MSF stepped up efforts to respond to COVID-19 in Lebanon and support the national health system in dealing with the pandemic. We temporarily turned our hospital in Bar Elias, in the Bekaa Valley, into a COVID-19 facility and now support an isolation center in Sibline, in the south of the country. MSF teams are also involved in testing, health promotion, and training activities in different locations across the country. Lockdown measures, although necessary, have worsened people’s economic difficulties.

“My husband used to find daily laborer jobs in agriculture or construction,” said Samaher, a 40-year-old Syrian refugee who lives in an informal tented settlement in Akkar governorate, near the Syrian border. “But with the economic situation and the coronavirus, it has become more difficult. He only works two or three days a week, and sometimes there’s no work for [two weeks]. When he doesn’t find work, we have to borrow money from the neighbors so we can buy food.”

A heavy psychological toll

For many people in Lebanon, whether they are Lebanese, refugees, or migrant workers, the current economic crisis and the deteriorating living conditions come on top of other traumatic events and stressful experiences, such as conflict or displacement, disrupting psychological wellbeing. Many patients who request MSF’s mental health services in Lebanon show symptoms related to emotional distress, depression, anxiety, and hopelessness.

“I feel completely down and useless. The economic situation in the country is a disaster. I only hope we won’t end up in the streets,” said Tawfik, a Palestinian refugee living in Shatila camp in Beirut. His family relies entirely on UN agencies and nongovernmental organizations to survive. “We are so tired,” adds Hanadi, his wife, unable to hold back her tears while she speaks.

As these challenges compound, people’s coping mechanisms are weakened and, for many, keeping their head above water is getting harder.

“We’re trying to help as much as we can in such a complex context and we are committed to continuing to doing so,” says Dr. Rehayem. “But our capacities are also limited and we can’t respond to all the needs. It is disheartening to see the population’s vulnerability increasing and more people requiring medical support.”

More than 600 MSF team members provide free medical services to people living in Lebanon, including mental and sexual and reproductive health care, pediatrics, vaccination, and treatment for non-communicable diseases.

MSF first worked in Lebanon in 1976 and has been present in the country continuously since 2008.