“After the assault, I thought I would take my own life,” said Charlotte*, an 18-year-old survivor of sexual violence. Charlotte is from Bangui, the capital of Central African Republic (CAR). After her mother died, her father rejected her so she went to live with her aunt and her uncle. One day, her uncle raped her while the rest of the family was out. When Charlotte told her aunt about the rape, she did not believe her. So she went to the police, but they wouldn’t help her. Charlotte felt completely alone and desperate.

After speaking with her cousin, she decided to seek help at the Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) Tongolo support center, which is dedicated to treating survivors of sexual violence. Charlotte is one of more than 6,000 people who have received medical, psychological, and psychosocial care from MSF in Tongolo projects since 2017 after suffering sexual violence. “The only advice I have to give you if this happens to you, don't worry and go to the hospital,” said Charlotte. “That's how you're going to get your health [back].”

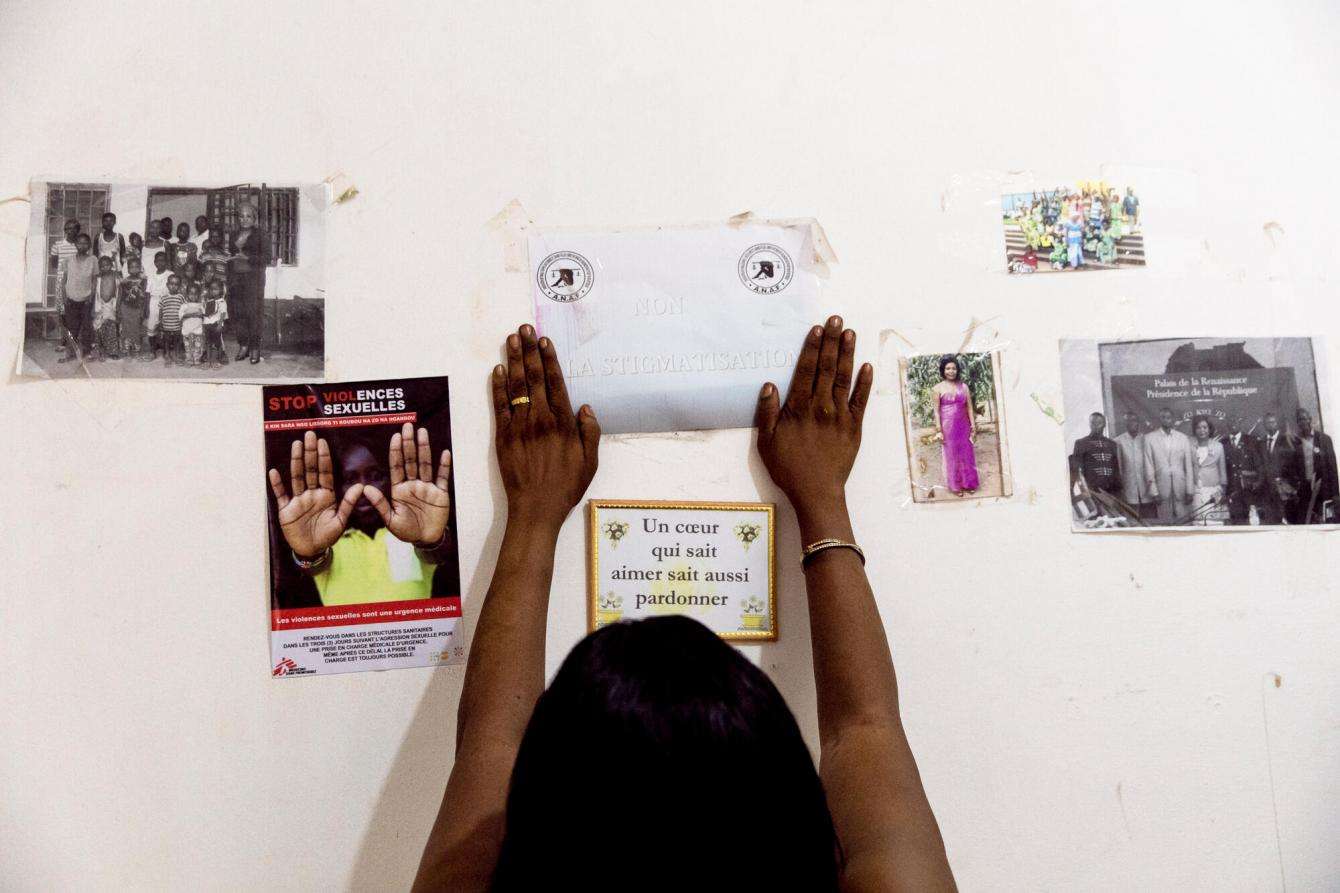

Sexual violence has become a public health crisis in CAR, and women and children are most affected. The country has endured years of conflict, but assaults are not only perpetrated by members of armed groups. They are often committed by someone the victim knows—friends, neighbors, or relatives. And although access to medical and psychological care has improved over the years, the resources available to survivors remain insufficient.

To better meet the massive needs, in 2017, MSF launched the Tongolo project in two health facilities in Bangui, in Bédé-Combattant health center and the Hôpital Communautaire. “Tongolo” is a Sango word—the primary language spoken in CAR—meaning “star” in English and was chosen to symbolize hope: A bright star in the dark sky. MSF expanded the project in August, 2020, and opened the Tongolo support center, where Charlotte was treated.

“The Tongolo initiative strives to provide free, high-quality, and [comprehensive] care accessible to everyone,” said Bilge Öztürk, MSF’s project coordinator.

Alarmingly, 52 percent of all people treated at Tongolo projects in 2020 were minors, and 95 percent were women and girls. Axelle Franchomme, Tongolo’s medical advisor, believes the data from Tongolo is representative of the sexual violence crisis throughout the country. Minors are the most vulnerable and the most sensitive patients to care for—if they do not receive appropriate care, these violent events can have a long-lasting impact on their future.

Suffering in silence

In 2020, 56 percent of the patients seen by MSF staff said that they knew their attackers. As the sexual violence remains a taboo survivors are often forbidden from talking about their experiences for fear of the shame it could bring their families.

“For the family, when a relative is sexually assaulted, the fault is [placed] on the person who was abused . . . who is already in a difficult situation and who was incapable of defending themselves against their aggressor,” said Aimé-Césaire, a mental health counselor. “The survivor deserves respect and psychological support from the family, but this is often not the case.”

Incidents of sexual violence are often resolved within the community or between family members, neglecting it as a medical emergency for which victims needs care. “Silence leads to [shattered] ambitions, broken families, sickness, dysfunctional relationships, and ruined lives,” said Gisela Silva, a mental health supervisor.

For male survivors, the situation is even more complicated. Many are afraid to speak up and only a handful make it to the Tongolo facilities for treatment. They are reluctant to ask for help, as there is significant community pressure and stigmatization. MSF has therefore adapted the program to provide care to men, and 111sought care from Tongolo projects in 2020.

Célestin* is a sexual violence survivor from Bangui who received care from MSF. Célestin is blind, and one night he kindly offered shelter to a person he thought he knew, but that person sexually assaulted him. “I was sleeping, and he came out of nowhere with bad intentions,” said Célestin. “He was drunk and forced me to do things I did not want to. I started to panic; I was so scared. He beat me but I managed to escape.”

Comprehensive care

The invisible consequences of sexual violence include post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression. Some people have thoughts of suicide—some attempt to take their own lives.

Access to psychosocial support is essential to prevent or reduce mental illness and psychological suffering caused by sexual violence. Survivors presenting symptoms should be admitted for care and linked to a psychologist or psychiatrist as soon as possible.

“The objective is to accompany survivors in their healing journey, to help them solve their problems and become strong enough to resume their lives,” said Franchomme, the medical adviser.

Following rape, treatment that prevents HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, as well as vaccinations against hepatitis B and tetanus, must be carried out as soon as possible—within three days of the event. Female patients also receive emergency contraception to prevent unwanted pregnancy.

However, in 2020, only 26 percent of MSF’s patients arrived within 72 hours of the assault. Through community health workers and radio announcements MSF tries to raise awareness about the importance of seeking care within this time frame. “We hear on the radio that we should go to the Tongolo center as soon as possible so that they can solve our problems,” said Célestin.

Legal and social needs

Beyond the medical and mental health consequences of sexual violence, rebuilding the future can be daunting to survivors due to legal and socioeconomic challenges. MSF connects patients to a social worker, but there are currently very few social and legal services available in CAR. There are also issues of impunity linked to sexual violence and criminal proceedings only happen in Bangui.

A few months ago, MSF established a space to host local and international organizations specializing in legal, protection, education, and socioeconomic support was in the Tongolo center so that survivors can access all the services they need in one place.

But the deck is still stacked against survivors. In January, CAR’s government imposed a temporary curfew and restrictions on movement in response to the increase in violence and political turmoil. This has created another barrier for survivors, as some people prefer to visit the Hôpital Communautaire at night to avoid stigmatization. Sexual violence perpetrated by armed groups has also increased, and, since December, the majority of our patients have been attacked by fighters.

There is still a long way to go to identify, treat, and adequately assist all survivors of sexual violence in CAR, but MSF remains committed to highlighting this crisis and caring for as many people as possible.

*The names of patients have been changed to protect their identity.

MSF has worked in CAR since 1997. We run 13 projects in Bangui, Bria, Bangassou, Bambari, Kabo, Batangafo, Paoua, Bossangoa, and Carnot. Treatment for survivors of sexual violence has been integrated into all projects. The Tongolo team, in collaboration with MSF’s emergency mobile team, is also intervening in other places across the country impacted by increased violence, including sexual violence.