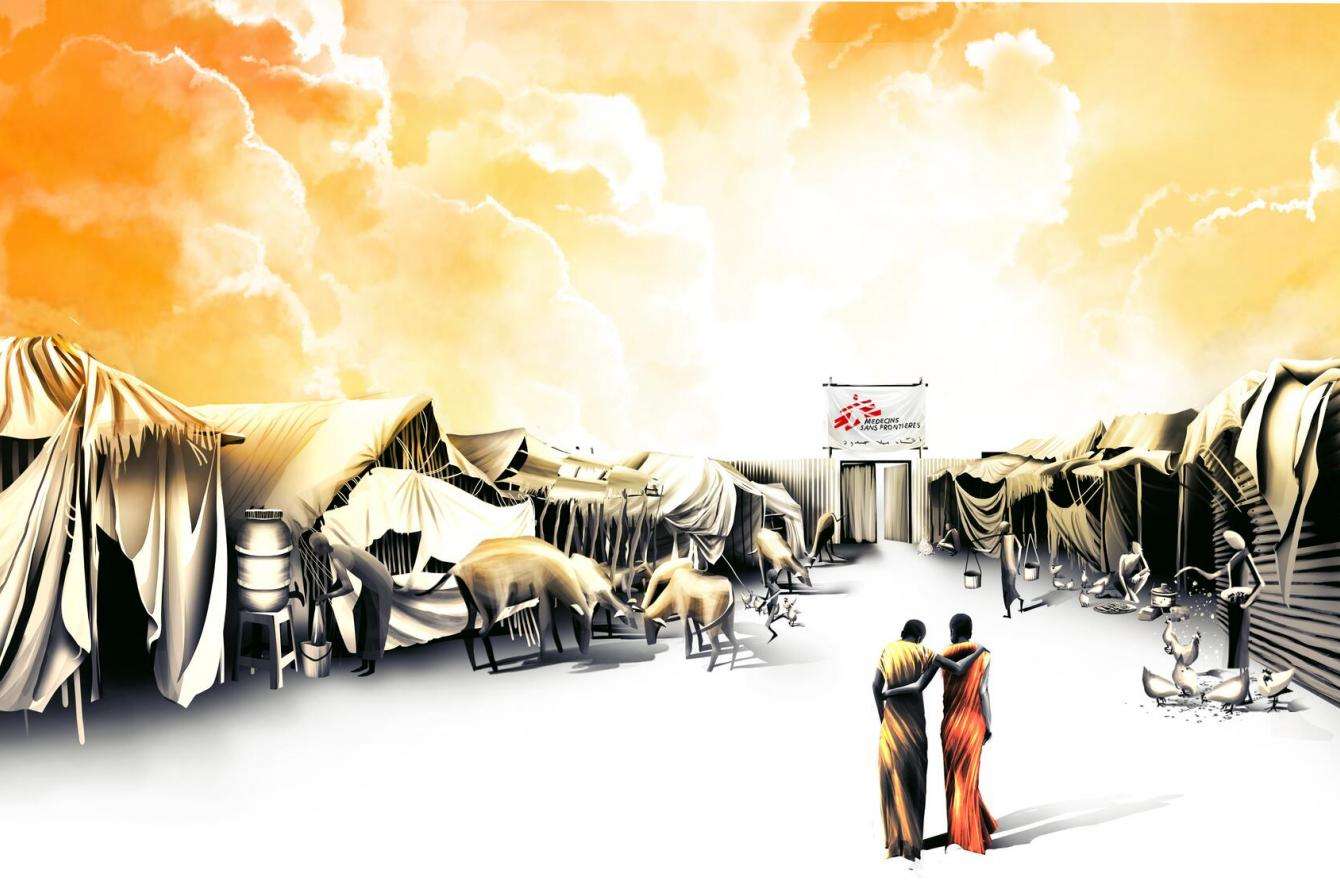

This month, South Sudan—the world's youngest country—marks its tenth birthday. In 2019, illustrator Ella Baron visited the town of Pibor to document the lengths that some mothers must go to reach maternity care in this part of the world.

The birth story of Maria and her mother Laito unravels as an extraordinary race with life-or-death stakes.

It is not, however, extraordinary at all. Their experience is a commonplace reality in areas of South Sudan where infrastructure is limited and where seemingly simple things can quickly become desperately complicated. The consequences of decades of violence are all around.

Having access to medical assistance in childbirth is important wherever you are in the world as complications can require specialist medical intervention to save the lives of both mother and baby.

In 2020, of approximately 2,300 health facilities in South Sudan, more than 1,300 were non-functional.

Fewer than half of South Sudanese people live within three miles of a functional health facility.

Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is doing its part to help, and in 2020 MSF teams assisted 13,400 births in South Sudan.

You can read Ella Baron's full original artwork of this astonishing story in the reader below.

A shortened and web-adapted version follows on this page, or download the PDF.

Laito's birth story, as told by her mother Chacha

“We come from the village of Mallodin; many days walk from Pibor. Laito was pregnant with her first child. When her contractions began, I called our neighbor who is skilled with births.

She came to our house and for three days we tried to help Laito to deliver. But still, the baby would not come.

’What’s happening? Is she going to be okay? Is the baby okay?’ I asked our neighbor.

’I’m sorry, I don’t know what’s wrong,’ she replied. ‘In Gumuruk town there might be MSF midwives who can help. But it’s many days walk from here… I don’t think she’ll make it.’

’Laito is strong’, I told her. ‘We’ll get there.’

Before sunrise, we started walking.

The contractions were so bad that Laito couldn’t walk alone so I had to support her always. It is rainy season and the path was full of water so that sometimes we were wading up to our waist.

When darkness came, we were still walking and I worried that we’d have to sleep by the path. But then we spotted a house.

They were strangers to us but when they saw Laito was pregnant they welcomed us into their home.

The next morning our host blessed our journey. By now, we were very weak. For days we’d had no food.

When Laito fainted, we’d stop to rest in the shade of a tree.

But we are no strangers to hunger. I remember hunger when Laito was a child. There will be hunger again.

Despite Laito’s weakness, I knew we had to keep walking. Eventually we reached a river too deep to walk. I paid two men to help us cross.

They had no boat—only a plastic cloth. The men placed the plastic on the water and swam it across.

We are not able to swim. Only this thin sheet supported us. There was too much water. I thought the sheet would fold and we would fall.

Then the crocodiles would come. Or we’d just sink deeper and deeper until all three of us drowned. Laito was so afraid.

It took us two days to walk to Gumuruk. But at the clinic, they couldn’t help us.

’I’m so sorry,’ a nurse at the MSF clinic said to us, ‘you have to go to Pibor where they have better facilities. It’s possible she needs a C-section.’

’But the path’s flooded,’ I said, ‘we’ll never make it.’

’I’ll message MSF Pibor—they’ll send a boat,’ said the nurse.

All we could do was wait and hope. But I worried to myself. Perhaps they will not come, I thought. Perhaps the baby is already dead. Perhaps I will lose Laito, too.

We waited two days and then Maria the midwife came by helicopter.

[MSF sent midwife Maria by helicopter because, at that time of year, the river is too thick with weeds for boats to travel. Maria, incidentally, is who Laito named her baby after.]

After the helicopter arrived, many things started to happen very fast.

Then, when it seemed the contractions had lasted eight seasons instead of eight days, everything came to a standstill. Except for her. And she was the only thing that mattered.

Now, we have to go home. Laito is my eldest, but I also have six other children. My co-wife is looking after them, along with her own four, but my youngest child will be needing my milk.”

Shortly after Maria, Laito, and Chacha’s story was recorded by Ella, the worst floods in living memory hit Pibor.

The town was entirely submerged leaving almost everyone to seek shelter on the only remaining island of high land. Increasingly congested, with only one borehole and no latrines, living conditions rapidly deteriorated.

When the floods eventually receded, a resurgence of intercommunal tensions sparked a new wave of violence, forcing local communities to flee their homes again.

We know that Chacha, Laito, and baby Maria safely returned to Gumuruk three days before the floods. We can only hope that the strength they demonstrated getting to Pibor enabled them to get home and stay safe.