Doctors Without Borders/ Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has worked for many years with the Rohingya people, who are among the most persecuted ethnic minority groups in the world. They have lived in Myanmar for centuries but have historically been denied citizenship by the country’s government, leaving them stateless. The Rohingya have also been forced to flee successive waves of violence in Myanmar over decades. In August 2017, security forces in Myanmar's Rakhine state led a campaign of extreme violence and persecution that triggered a mass exodus.

“The Myanmar army shot us on sight without any reason,” said Solim [name changed to protect anonymity] a Rohingya man who fled to Bangladesh with his family. “They killed us indiscriminately. They burned our houses. On August 25, 2017—a hartal day [a mass protest]—we were informed that there were plans for a massive cleansing. We understood by then that we could not live in that country. We left.”

More than 740,000 Rohingya have fled Myanmar since August 2017, crossing the border into Bangladesh’s Cox’s Bazar district. They joined hundreds of thousands of people from the community who were already living in the sprawling refugee settlements of Nayapara and Kutupalong.

Temporary solutions for a protracted crisis

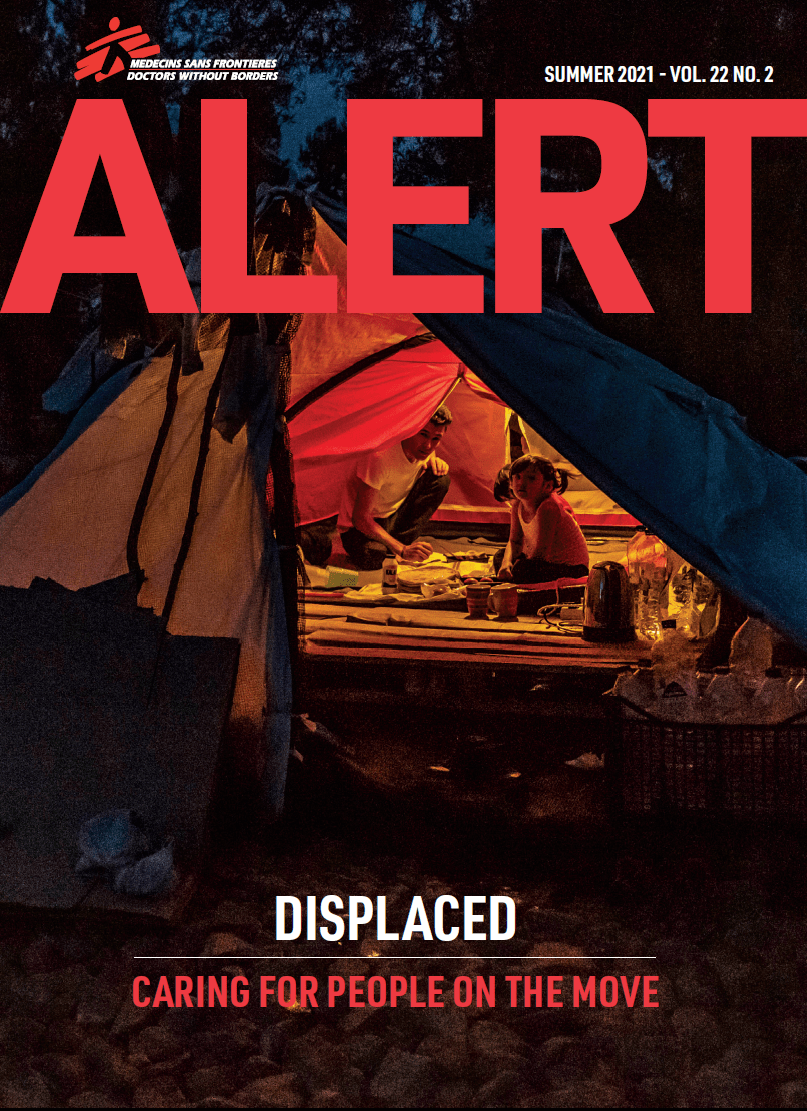

Today, the Cox’s Bazar district hosts nearly 900,000 Rohingya people, and the massive camps have turned its hills into a sea of shelters cut off from the world by barbed wire and razor fencing. It’s the largest refugee camp in the world, but the refuge provided by the Bangladeshi government was offered as a temporary solution. As a result, most shelters are made from temporary materials such as bamboo and plastic sheeting that flood in the rain, offer no protection from intruders, and are built on top of each other. In March, a fire spread rapidly, destroying the shelters of 50,000 people and six health clinics, including one run by MSF. Fifteen people died.

“The camps are congested, and we are seeing a really worrying environmental impact on people living there,” said Bernard Wiseman, who was MSF’s head of mission in Cox’s Bazar from June 2020 to June 2021. “[They are] underfunded, especially for water and sanitation services—only a fraction of funding requested for these services was received in 2021. This has medical consequences—we’re starting to see a lot of skin infections and other issues related to deteriorating water and sanitation services.”

On top of this, Rohingya people are not given refugee status in Bangladesh (Bangladesh has not acceded to the 1951 international refugee convention). This means they are denied the right to education, employment, free movement, and access to social security or public assistance—just a few of the rights afforded to refugees under United Nations (UN) conventions.

“We were oppressed in Myanmar,” said Solim, who worked with MSF for 20 years in Rakhine state. “Our children did not have a chance to get proper education. Now we have no fear of being tortured and our children are getting an education. But it has been four years, [and] we do not have any jobs.”

The Bangladeshi government does allow Rohingya people to volunteer with humanitarian organizations within the camp and receive a small sum as compensation. The number of available volunteer positions dropped significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic as the Bangladeshi government imposed strict lockdown measures and cut the number of humanitarian actors allowed into the camp by 80 percent.

“This severely impacted the livelihoods of many Rohingya [people] and has forced them to make some tough decisions,” said Wiseman. Desperation brought on by the pandemic restrictions, which exacerbated a lack of opportunity and an uncertain future, has led to a spike in crime within the camps. “One of the symptoms of the COVID-19 restrictions is an increase in violence and extortion. There is a stronger prevalence of gangs, lots of violence, and we are seeing more trauma injuries in some of our hospitals. There is a stronger prevalence of armed groups that has created real insecurity in the camps.”

Impossible choices

With no viable solutions in sight, Rohingya people in Bangladesh are forced to make impossible choices about their futures. Some make the dangerous journey on trafficking boats across the Bay of Bengal to join the more than 100,000 Rohingya residing in Malaysia. Often these boats are caught by Malaysian authorities, but when they turn back to Bangladesh, they are blocked by Bangladeshi authorities and stranded at sea for weeks—sometimes months.

Approximately 20,000 Rohingya people have agreed to be relocated to the island of Bhasan Char, a sandbar in the middle of the Bay of Bengal that has only existed for about 15 years and has never been inhabited. The Bangladeshi government plans to eventually house 100,000 Rohingya refugees there, but the only way to reach the island from the mainland is by taking a three-hour boat ride with the Bangladeshi military. Once they arrive, people are not allowed to leave.

While the island is less overcrowded than the camps in Cox’s Bazar, MSF is extremely concerned about this temporary solution. “The relocation to Bhasan Char is a consequence of the failure of the international community to provide a solution to what has become a protracted refugee crisis,” said Wiseman. “It is just one of many issues that the Rohingya have faced for decades— an ordeal that includes state-sanctioned violence, persecution, discrimination, and the denial of their basic rights.” And with only rudimentary primary health care being provided on the island, it is unknown how emergency or specialty medical needs will be handled.

Others have made the difficult decision to return to Myanmar, “a country they fled at gunpoint that is in an even less stable situation now,” according to Wiseman. Myanmar plummeted further into crisis after a military coup in February 2021. Public health services remain severely disrupted and doctors and nurses continue to be the targets of violence, leaving people struggling to access care. In Rakhine state—an area where many people rely on humanitarian aid—health organizations are scaling back activities as they struggle to access cash and get supplies into the camps. MSF teams are seeing a spike in people seeking treatment for health problems related to poor hygiene conditions.

A mental health crisis

The increase in violence, compounded by deteriorating living conditions and an uncertain future, has created a mental health crisis among the Rohingya people in Cox’s Bazar.

“When a group’s future is uncertain and when a population is not integrated into a society, this creates a feeling of a lack of safety,” said Kathy Lostos, MSF mental health activity manager. “Feeling that your life is under threat can lead to helplessness, believing that ‘nothing that I do will matter,’ and this can have a huge impact on people’s mental well-being.”

From January to December 2020, MSF teams provided 36,027 group and 32,336 individual mental health consultations in the camps—a 61 percent increase compared to the previous year.

“We lost our belongings, our hopes, and our future,” said Solim. “But we are also human—we have [a] right to live well.”