Reaching the hard-to-reach

One of the biggest challenges MSF faces is getting malaria care to those who need it the most: people living in remote, insecure areas with little or no health care access. Whether because of seasonal rains that flood roads or active armed conflict that forces people to leave their homes, finding better ways to effectively reach and treat our patients where they are is a challenge MSF is always trying to overcome.

One strategy is to use mobile clinics that travel to remote villages without health clinics nearby. For example, in the Central African Republic, many regions are isolated because of armed conflict, which has disrupted the already weak government health services. There is no public transportation for people to travel to larger towns. MSF mobile clinics drive two to three hours to visit remote villages to test for and treat malaria, transferring those already severely sick to hospitals.

Another strategy is to train and equip community health workers with supplies for providing care in areas MSF teams can’t reach consistently reach. In South Sudan, MSF has de-centralized simple malaria care by training community health workers who can test for and treat malaria in clinic teams. When people are forced to leave their homes because of fighting nearby, these health worker teams move with them since they are part of the community, and continue providing health care. The teams run clinics wherever they are six days a week, caring for thousands of people displaced by the conflict while on the move. MSF re-supplies them with tests and drugs when security allows.

Community health workers in all projects also pass on vital educational messages about the importance of using mosquito nets wherever possible and seeking treatment for children when they have fever.

Prevention activities

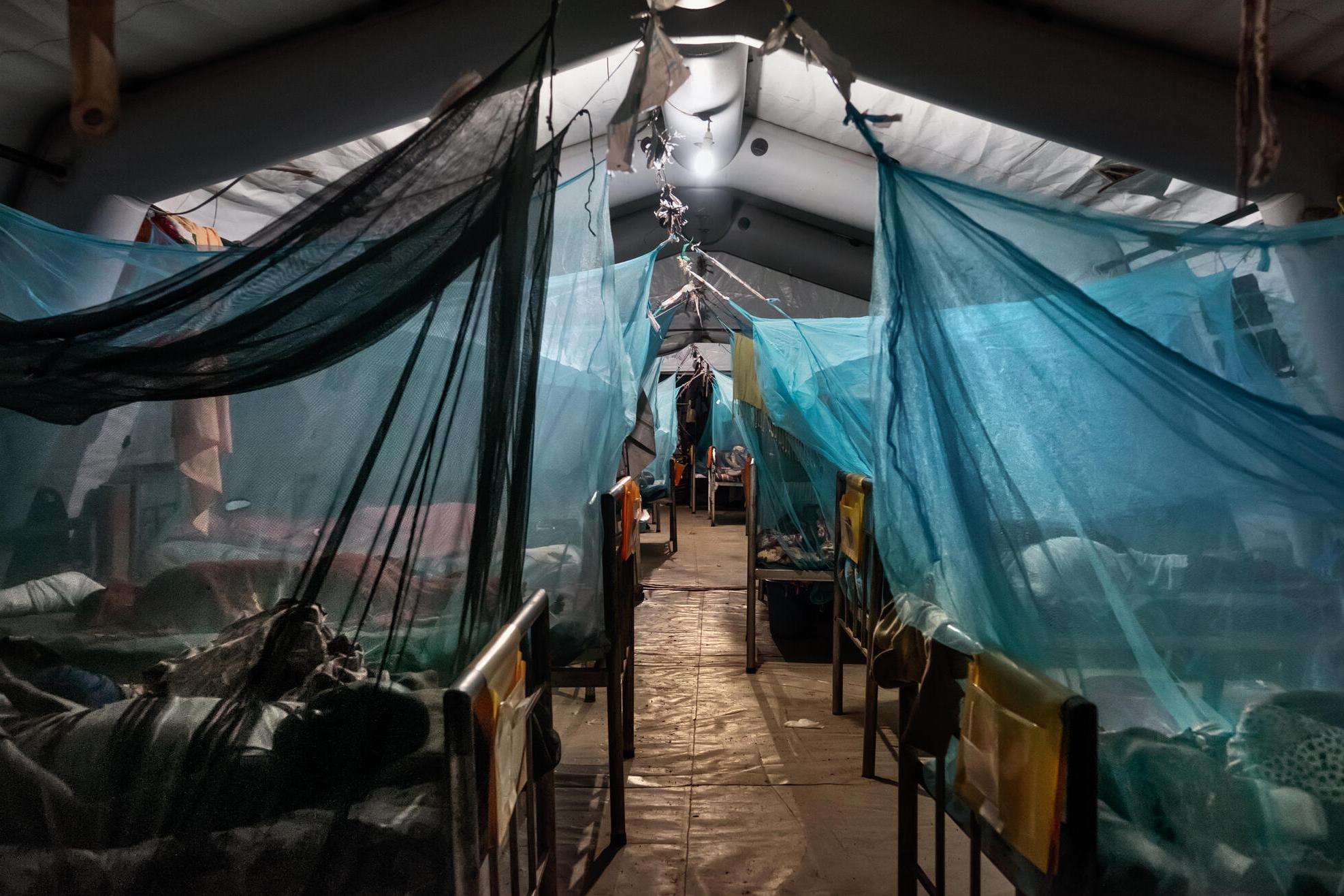

Our programs incorporate various prevention approaches, depending on context—from distribution of mosquito nets to spraying larvicide to prevent the breeding of mosquitoes. In some affected regions malaria is highly seasonal, with the number of infections increasing exponentially during the few months of the rainy season.

Innovating against resistance

In Southeast Asia, a key epicenter of resistance to anti-malarial drugs globally, our projects are actively researching the emergence of artemisinin-resistant malaria and piloting strategies to combat it. We’re also working to find and treat patients with artemisinin-resistant (ACT) strains of malaria, and along the way adapting strategies and tools to better meet the challenges of resistance and malaria elimination.

Advocacy

Malaria spikes are too often treated as an unpredicted emergency despite the fact that we now have tools—from weather monitoring to close surveillance of new cases—to anticipate the onset of malaria peaks. Countries need to use these tools better to prepare for seasonal outbreaks by pre-positioning preventive antimalarials and mosquito nets that can be distributed once the rainy season begins and by investing more in community-based care.