Kasaye sits on his bed in the intensive care unit of the Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) health centers in Abdurafi, Ethiopia, a bottle of soda and some cookies in his hands. He looks incredibly frail and the simple acts of drinking and eating require immense effort.

“This is the thirteenth time that I have come to MSF for kala azar treatment,” he says.

Deadly disease

Kala azar (also known as visceral leishmaniasis) is the second largest parasitic killer after malaria, which makes it one of the most dangerous neglected tropical diseases in the world. Every year, it infects between 200,000 and 400,000 people, mostly in Asia, East Africa, and South America, and around 50,000 die from it. It usually spreads through the bite of an infected female sand fly. Initially kala azar causes skin sores or ulcers at the site of the bite. Generalized symptoms include prolonged fever and weakness, as the disease eventually attacks the immune system.

“I was first diagnosed with the disease in 2002,” Kasaye continues. “I received treatment and the symptoms disappeared. I thought I was cured.”

Disastrous co-infection

Once treated, patients usually become immune to the parasite. However, this was not the case for Kasaye who, one year later, was diagnosed with HIV. HIV can prevent patients from being fully cured of kala azar, exposing them to the risk of relapse.

To make things more complicated, kala azar and HIV co-infection is disastrous because both conditions weaken the immune system and reinforce each other, leaving a person vulnerable to other opportunistic diseases like tuberculosis, malaria, and dysentery. Ethiopia has a very high number of co-infected patients, with 20 to 40 percent of kala azar cases occurring in HIV positive people.

A vicious cycle of poor living conditions

“During the years, I suffered from 12 other kala azar infections and the time between relapses is becoming shorter,” says Kasaye. “I came to Amhara from Tigray as a migrant farm worker but kala azar has made me weak and I can’t work in the fields anymore. Now I live in the streets and I have no choice but to beg for money.”

Economic status seems to be a determining factor when it comes to kala azar relapse in HIV co-infected patients, as people in poor living conditions are more exposed to sand flies—the carrier of the parasite—and are further debilitated by the lack of food.

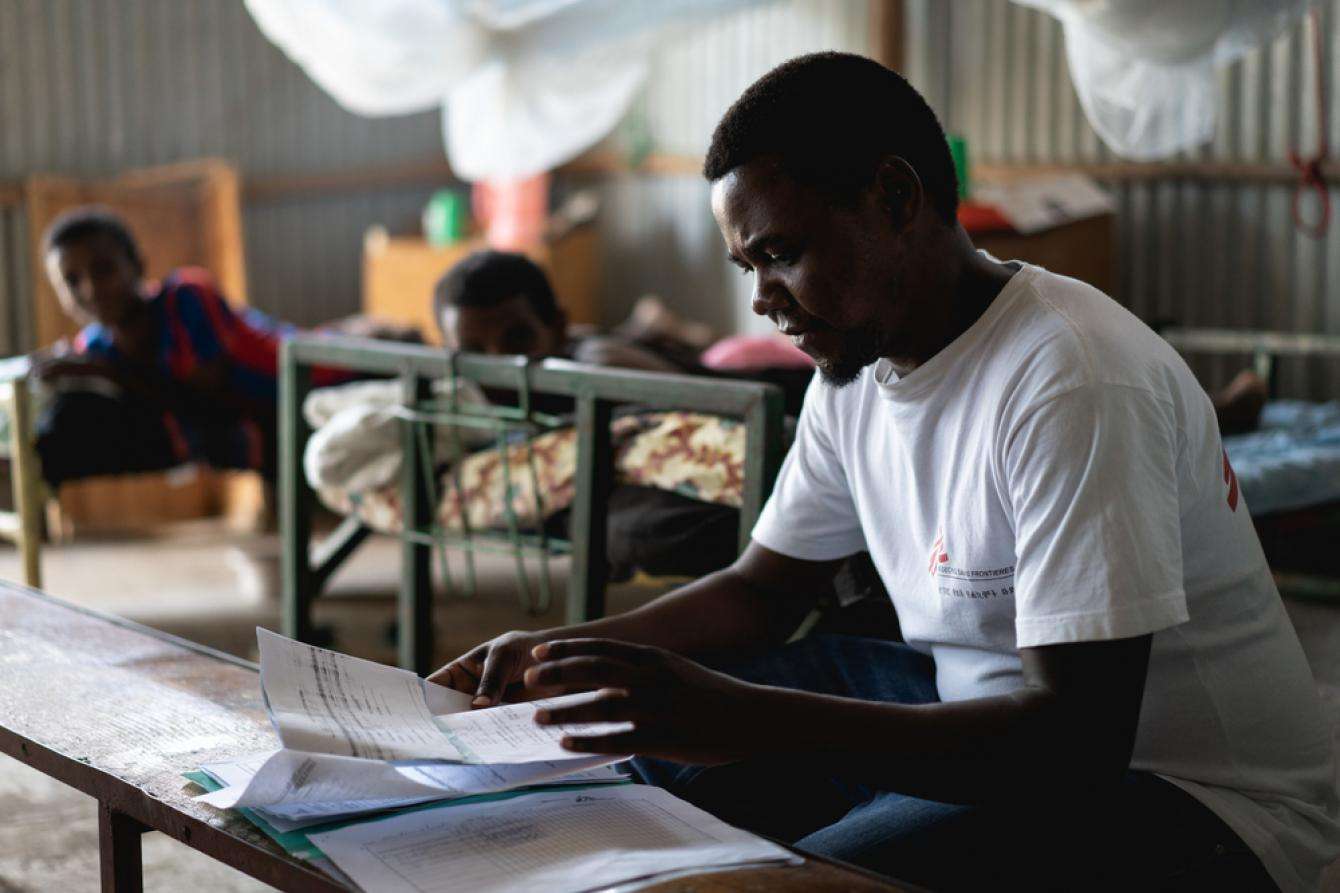

“Kala azar is endemic in the Abdurafi area and that’s why MSF decided to set up its intervention here,” says Dr. Ernest Nshimiyimana, medical team leader for the Abdurafi project. “In addition to providing treatment for kala azar and HIV, we also run a state-of-the-art laboratory for the diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis.”

Difficult diagnosis

Diagnosing kala azar is a complicated matter. Rapid diagnostic tests are available in most health facilities, but they are reliable only with patients infected for the first time (a condition called primary kala azar).

“The MSF clinic in Abdurafi is one of the few places in Ethiopia where the presence of active kala azar parasites in a patient’s body can be accurately diagnosed,” continues Dr. Ernest. “To determine whether a patient is cured or not, or to diagnose kala azar in suspected relapse cases, a spleen or bone marrow biopsy is required. To analyze these samples, you need a specialized lab and here we have all the equipment we need.”

The services available at this lab are essential. Mortality rates are 14 times higher in HIV co-infected and relapse patients. Therefore, a timely diagnosis is instrumental in saving lives.

“The majority of health facilities in Ethiopia do not have the tools or the expertise to carry out many of the tests that we perform here,” says Mercy Oluya, MSF lab manager. “Some of the tests can also be very expensive, but MSF in Abdurafi offers all free of charge We brought in experienced lab technicians and all the necessary equipment. We are also training the Bureau of Health staff that share the lab with us and perform all the other routine tests for our patients.”

Fostering understanding and prevention

The lab is also used to study the prevalence and incidence of kala azar in HIV patients in partnership with the Institute of Tropical Medicine Antwerp (ITM), the University of Gondar, and the Ethiopian Regional Health Bureau in Amhara. Research began in October 2017 and will run for four years.

“We are especially looking for HIV positive patients who develop the kala azar disease even if they are on antiretroviral therapy. Here in Ethiopia we have quite a few cases,” says Aderaju Kibret, MSF’s medical research manager.“We monitor patients for a minimum of three months and up to two years. The aim of the study is to improve our understanding of the disease and develop better prevention methods.”

Only a few institutes or pharmaceutical companies are investing time and money into kala azar research, with the consequence that very few new drug treatments are being developed. Kala azar primarily affects people who cannot afford to pay for the drugs, thus representing an unattractive market for drug companies.

“I know many people who have kala azar and I have firsthand experience of how it can affect a person’s life,” says Kasaye. “I want to contribute to the elimination of the disease in Ethiopia.”

MSF has been providing up-to-date screening and treatment for complicated kala azar co-infected patients with HIV/AIDS and/or tuberculosis in the Amhara Region of Ethiopia since 1997. The Abdurafi project also offers treatment for snakebites—another neglected tropical disease—and provides support for emergency referrals.

|

ABOUT THE STUDY PreLeisH (Predicting Visceral Leishmaniasis in HIV-Infected Patients) is an observational prospective cohort study launched on October 11, 2017, in Abdurafi. The study investigates the asymptomatic period preceding the onset of active visceral leishmaniasis (VL) in over 1,000 HIV‐infected patients over a period of four years, as an avenue to develop an evidence‐based screen and treat strategy to prevent progression to active VL. PreLeisH is implemented in a collaboration between MSF, (ITM), the University of Gondar, and the Ethiopian Regional Health Bureau in Amhara. The unique context in the northwestern Ethiopian lowlands of a very high HIV/VLco-infection rate provides unique opportunities for research on management of HIV/VL. MSF is the only organization in the region with access to patients as well as capacity to do clinical research. Abdurafi has developed into a unique center of excellence for HIV/VL treatment and, over the last few years, MSF has established effective research collaborations with ITM, DNDi, and the University of Gondar. Over the past 17 years, MSF has carried out ten kala azar studies in the Amhara Region of Ethiopia, mainly focusing on HIV/VL co-infection. The impact of these studies has been substantial. They have resulted in policy changes at the national and international level and have driven WHO recommendations and international research agendas. |