Note: Since Marie-Aure wrote this testimony, MSF has evacuated staff from Al-Aqsa Hospital upon receiving evacuation orders.

Each day, dozens of patients are rushed into the emergency department of Al-Aqsa Hospital in central Gaza. No triaging is possible at the bomb sites, so it’s a race for ambulance crews to save the people that can still be saved.

The emergency department is in chaos—critically injured patients lying on cardboard boxes because the beds are full, and journalists attempting to tell the story of what’s happening to people who seem determined not to listen. As the journalists step back to record the scene, they sometimes tread, accidentally, on the bodies lying on the floor. Some days, the hospital receives more dead than injured.

We first visited Al-Aqsa on November 23, the day before the “humanitarian pause” was announced. That day, the hospital received 314 wounded people and 121 who were dead on arrival or died shortly after. My Palestinian colleagues reminded us that this is not a new conflict: “It’s always like this before a truce.”

After that first visit, our team began working alongside the staff at Al-Aqsa. The hospital had capacity for 200 inpatients before the war. At the end of December, they had more than triple that number.

Babies who never learned to walk, and never will

One day we were alerted that an MSF staff member and his family had arrived at the emergency department, badly injured. Colleagues rushed to find them in the chaos.

Later, Dr. Samir* told me, “I had to make a choice—I saw Ghassan* and his son, they needed me, but next to them I saw a woman critically injured, who also needed me. What was I supposed to do?”

Health care workers are forced into decisions like this every day in Gaza.

Ghassan’s son had been hit by shrapnel. He underwent multiple surgeries that day, including injuries to his throat that affected his ability to speak. His mother lost an eye. That day, when Dr. Samir came out of the operating theatre at 1 a.m., his MSF jacket was covered in blood.

By the end of December, the team in our wound dressing unit was seeing an average of 150 patients per day, almost all with burns or blast injuries. Many were children. One of MSF’s surgeons told me about dressing the wounds of babies who had lost their legs. It stayed with him. Babies who had never learned to walk, and never will.

Some of those children have a new acronym written on their file: “WCNSF,” which stands for “wounded child, no surviving family.”

Nine-year-old Salma* is one of thousands of WCNSFs. She suffered a fractured skull when the house her family was in was shelled. One of her legs was broken; the other had been amputated. We met her in the intensive care unit. She still didn’t know that she was the only one who made it out of the rubble alive. The exhausted staff wanted to let her recover physically first.

One of the biggest challenges facing hospitals in southern and central Gaza is bed capacity. The beds are needed to treat patients in critical condition, but those who have been stabilized have nowhere to go. Where should we send a patient like Salma? What do we say to her?

Health care is under attack, and needs are growing

Like the few other hospitals still partially functioning in Gaza, Al-Aqsa can only provide trauma care. Health facilities have faced attacks and evacuation orders, and have been starved of medical supplies, clean water, and electricity. I can barely describe the destruction of health care I have witnessed. Many hospitals and primary health centers have been forced to close; services like maternity care or treatment for chronic conditions essentially no longer exist.

So are the people of Gaza no longer sick? Is there no more appendicitis? No asthma or gastroenteritis? The truth is that in overcrowded shelters without food, water, and the most basic hygiene conditions, people are sicker than before. But they no longer have access to health care.

In mid-November, MSF started supporting the Shohada Health Center, the biggest provider of primary health care in Khan Younis. The needs were huge. After just one week, we had already provided outpatient consultations for more than 600 people, half of them under the age of five. They had respiratory infections, skin diseases, or diarrhea, all of which can cause severe complications, especially in young children. All are a direct consequence of their dire living conditions.

Women were rushed in, so dehydrated they had collapsed. Mothers begged for baby formula— with nothing to eat, they could no longer breastfeed and their babies were hungry.

On December 1, as the “pause” ended, the neighborhood where the health center is located was ordered to evacuate. Our team was forced to leave and the health center ceased to function.

One of the thousands of patients who lost their access to health care that day was a five-year-old boy being treated by our psychologist. He had told her in a session that he wanted to die.

At Al-Aqsa Hospital, MSF’s mental health team held art sessions with children. Some drew their families, killed during bombings. They drew the legs and arms of their mothers on the ground beside their bodies. When they told me about this, I thought not only about children, but also about the psychologists holding this trauma while going through the same experiences themselves.

Heroes still need support

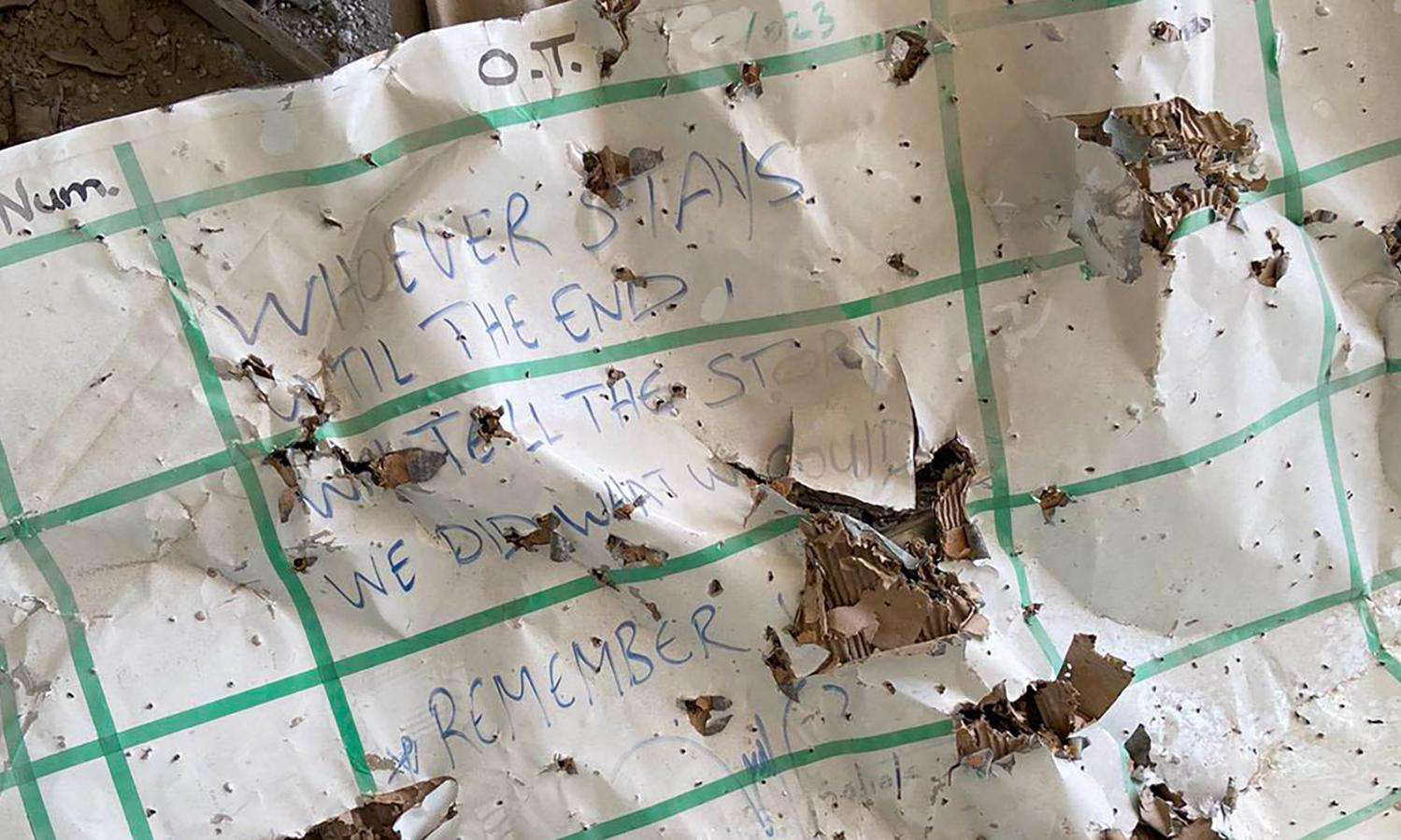

Our team members in Gaza have lost family members, homes, colleagues. One colleague learned on social media that her sister had been killed. She came to work anyway, [trying] to forget, because there was nothing else [she could] do.

An attack on Al-Awda Hospital killed two of our doctors, Dr. Mahmoud Abu Nujaila and Dr. Ahmad Al Sahar. The third member of their team wasn’t there that day—he had come to work with us at Al-Aqsa Hospital. Later, when two survivors of that same attack arrived at Al-Aqsa, this doctor was the one who dressed their wounds.

Health care workers in Gaza are called heroes. But calling them heroes suggests that they can magically alleviate this unbearable suffering on their own. It suggests they don’t need support.

The Dr. Samir was injured, his daughter saw him bleeding. She told him, “Doctors aren’t supposed to bleed.” They do though.

The illusion of humanitarian action

Foreign journalists often ask me how Gaza compares to other crises I have worked in. I say that in Gaza there is a humanitarian crisis, but no humanitarian response.

Israeli officials make claims about the number of trucks being allowed through Rafah daily, as if there is an acceptable ratio between the number of trucks and the number of people killed. But humanitarian aid is not about trucks, and the supplies being allowed in no way match the scale of the needs. A humanitarian response is one in which we can assess, plan, and work according to the needs of the civilian population. Instead, MSF and a few other international organizations are delivering very limited medical care under wildly abnormal conditions.

Health care workers in Gaza are holding the values of humanity in a time of great darkness. Meanwhile, the people who have the power to stop this humanitarian catastrophe do not take action. While they hesitate, doctors, nurses, and other Palestinians are being massacred.

When I left Gaza, I was asked by my colleagues to bear witness to their stories. I saw just the tip of the iceberg. And that tip was unbearable to see.

*Names changed to protect privacy