In early November, tensions between the national government in Addis Ababa and the northern region of Tigray escalated into violence. At the onset of the fighting in Tigray Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) was operating projects in Amhara and other parts of Ethiopia. The Amhara region is close to Humera, a strategic city in the western part of Tigray heavily affected by the fighting. After more than a month of fighting, the humanitarian situation continues to critically deteriorate.

On November 5, our team began supporting a ministry of health-run center in Midre Genet, a remote town that received an influx of people injured in the fighting in border areas. In just a few hours, the team switched from everyday medical activities to emergency assistance. In one week alone, MSF and ministry staff treated 265 casualties, many of them with severe injuries.

“We heard the launching, the heavy artillery, and it went on all morning,” remembers Sara*, a former MSF laboratory technician in Midre Genet. “The same day, we received the first wounded. They kept arriving in waves. On the first two days, we received soldiers—all very young. Then the first civilians came in by the truckload, packed into the back of vehicles.”

The fighting shifted to other parts of the Tigray region and the MSF team focused on supporting internally displaced people. Sara left Midre Genet soon after the acute fighting, as the influx of wounded reduced.

“When I left the project, there was still a sense of sadness and despair among the MSF team,” she says.

What the team experienced during these first days of clashes had a huge psychological impact on their mental health.

“They saw soldiers and civilians coming in, wounded or dead,” says Kaz de Jong, MSF staff health coordinator. “They had to do triage and make very difficult decisions. It was also hard for the nursing staff, who had to care for the people who had the best chances of survival and leave the others. That is so counterintuitive for their profession. And the sight of blood, suffering, and wounds can often leave stressful images.”

The situation is particularly difficult for our Ethiopian colleagues, with uncertain futures. Staff with relatives and loved ones who remained in Tigray, where there is a complete communication blackout, have yet to receive any news. Many have not heard from a number of their colleagues either.

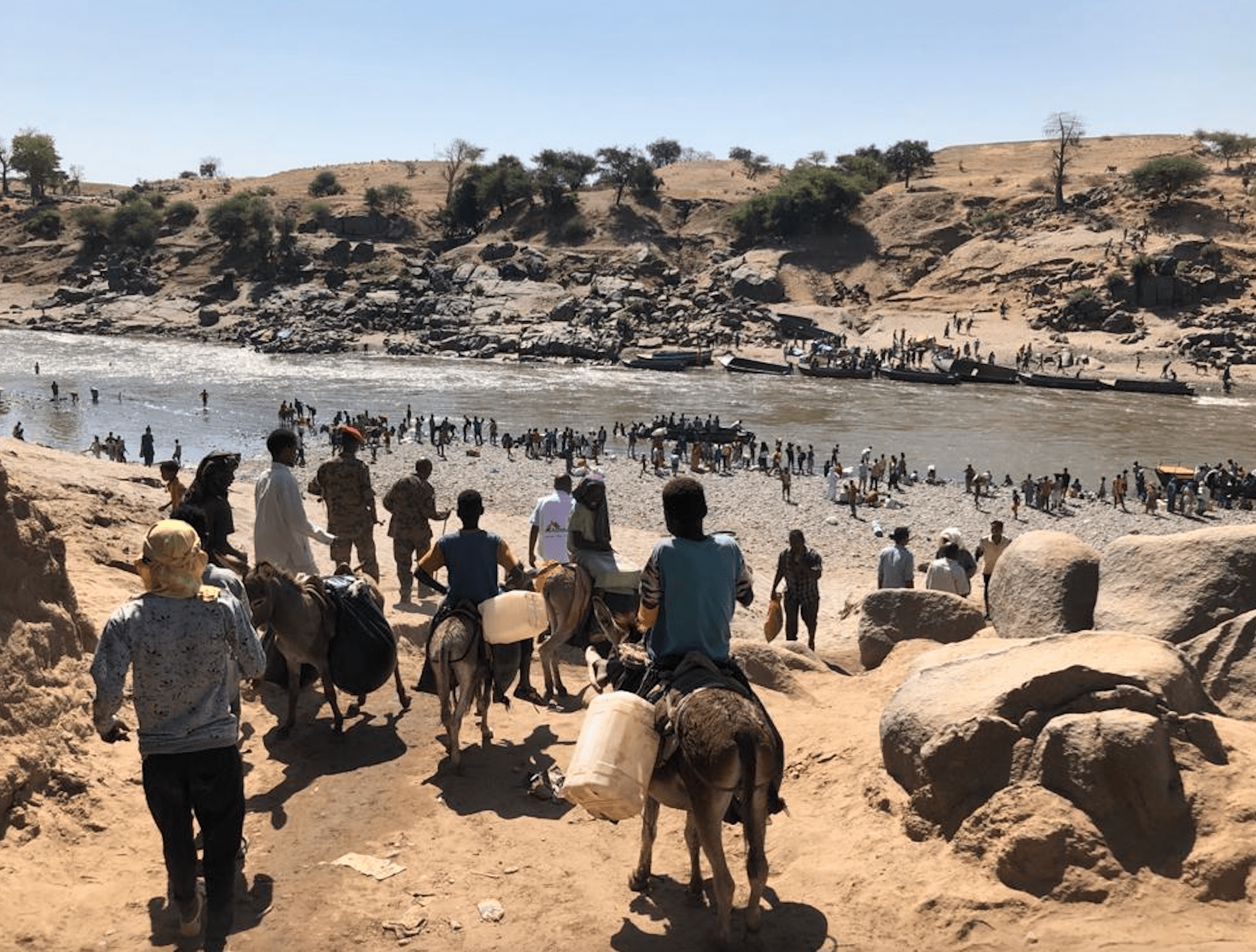

“Some of them were companions for years, and from one day to the next, they just disappeared, fled to other towns or neighboring countries without any notice,” says Kaz. “Every day, our Ethiopian colleagues see all these people who have been displaced because of the fighting and who are now living in small settlements around them, huddled together in very bad conditions. And, of course, before the fighting started, COVID-19 had already complicated their lives, preventing most children from going to school and increasing the number of unemployed people that they and their families have to support financially.”

“I cannot be happy, but I can be a bit happier”

In response to the crisis, MSF is providing mental health support to help health workers cope with the trauma they have experienced. The assistance ranges from phone calls to physical and psychological activities. In Ethiopia, as in any context of fighting and violence, our teams have benefited from group and individual sessions to aid them in better managing their daily stress.

The group workshops on stress management usually take place in five steps. First, participants are asked to make an inventory of all the things that cause them stress. They can be personal concerns, such as family issues, or broader ones, like the ongoing violence. Then the group chooses the most important stress factor they want to discuss. It can be overwhelming to think about multiple problems at the same time, so we ask them to focus in on one to develop specific coping strategies for it. The third step is to think about what is still functioning well.

“Our intention is not to push the problems aside, but rather to tell the whole story,” says Kaz. “Of course, this does not undo all the dramatic incidents, but looking at the whole story, including all the things that are still functioning well, allows them to be more inclined to look at their problems from a solution-oriented perspective. It takes time, effort and courage but people usually manage to switch, as they do not want to be stuck in unhappiness. At the end of the day, they end up thinking ‘I cannot be happy, but I can be a bit happier’”.

The last two steps involve thinking about how to improve the situation and make an action plan. These elements are essential to mitigating the jarring impact of the continuous and destabilizing violence. Reaching out to friends and colleagues, not only to talk about problems but also to share very simple things in their everyday lives, greatly reduces their stress and strengthens their sense of community.

The workshops also reinforce positive connections among the staff. In the Amhara region, our team is made up of Ethiopians from different backgrounds. They never mentioned this during the sessions. Instead, they focused on the fact that they had saved lives together, as a team. The guards who helped with patient traffic, the physicians who treated the wounds, the nurses who provided first aid, the lab technicians who carried out the blood tests.

“Everyone had his or her role and they worked together like a smooth machine,” says Kaz. “I must say that I have been in many situations, and the way the team rapidly switched from their previous activities—kala azar, TB treatment, snakebites and clinical trials—to go into a very efficient emergency mode was remarkable. Caring for and treating large numbers of people would not have been possible if they had not been able to do this. The staff are proud of this achievement and they have every right to be proud of it.”

* MSF staff member’s name was changed. The person requested to remain anonymous.

MSF has been working in Ethiopia since 1984. For more than 30 years, our teams have responded to emergencies countrywide, including malnutrition, malaria, acute watery diarrhea, the health needs of refugees and basic access to health care. In the Addis Ababa, Amhara, Gambella and Somali regions, we run regular projects in collaboration with government health institutions to provide host, refugee, and displaced people general and specialist health care, treatments for neglected tropical diseases, as well as medical and mental health support to Ethiopian migrants, most of them deported or repatriated from Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Lebanon. Our teams have also developed contingency plans to ensure the continuity of our current activities in the country during the COVID-19 pandemic.