In August 2017, the Myanmar military launched a violent campaign against the Rohingya community that resulted in a mass exodus to Bangladesh, where Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontiéres (MSF) ramped up activities to meet the increasing health needs. Today there are nearly one million Rohingya refugees living in overcrowded camps in Cox’s Bazar—now the largest refugee settlement in the world.

In the chaos of displacement, some Rohingya managed to take a few mementos with them—family photos, documents, cherished relics of their former lives. This is the story of four Rohingya refugees living in Cox's Bazar, and the precious remnants of home they still carry with them, six years later.

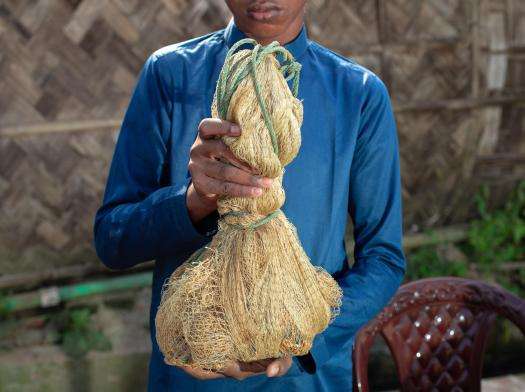

In Myanmar, Abdulshakour made his living as a fisherman, selling his catch at local markets. When violence erupted near his village, panic and chaos ensued.

"Everyone was scrambling to escape," he recalled. In the disarray, he was separated from his family for a harrowing 25 days. Their reunion came on their way to Bangladesh, a journey they took by boat.

During the escape, people were advised to carry only one essential item. For Abdulshakour, the choice was obvious—his fishing net. "I believed it would be useful here," he said. Now, however, he has a physical condition that prevents him from fishing.

Abdulshakour used this fishing net to make a living in Myanmar; today, he holds onto his old house number in hopes of returning one day. Bangladesh 2023 © Mohammad Hijazi/MSF

As the camps grow more crowded, so do the challenges of life in Cox's Bazar. Some families are resorting to selling their vegetable rations to supplement their meals. "We can't always get fish," said Abdulshakour, emphasizing the need for varied nutrition. The birth of another child amplifies the difficulties of their new reality.

Abdulshakour remains in touch with relatives who still live in Myanmar, and he continues to hear about ongoing restrictions that limit their movement and safety. Still, his heart remains tethered to his homeland.

"I deeply miss my land and my family," he said, echoing a common sentiment. Among his belongings is his old house number—a tangible link to the existence he once knew. "I hold onto the hope of returning."

When tensions in Myanmar escalated, Melua's family made the difficult decision to leave their home. They eventually arrived at the refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar on the Islamic holiday of Eid Al Adha.

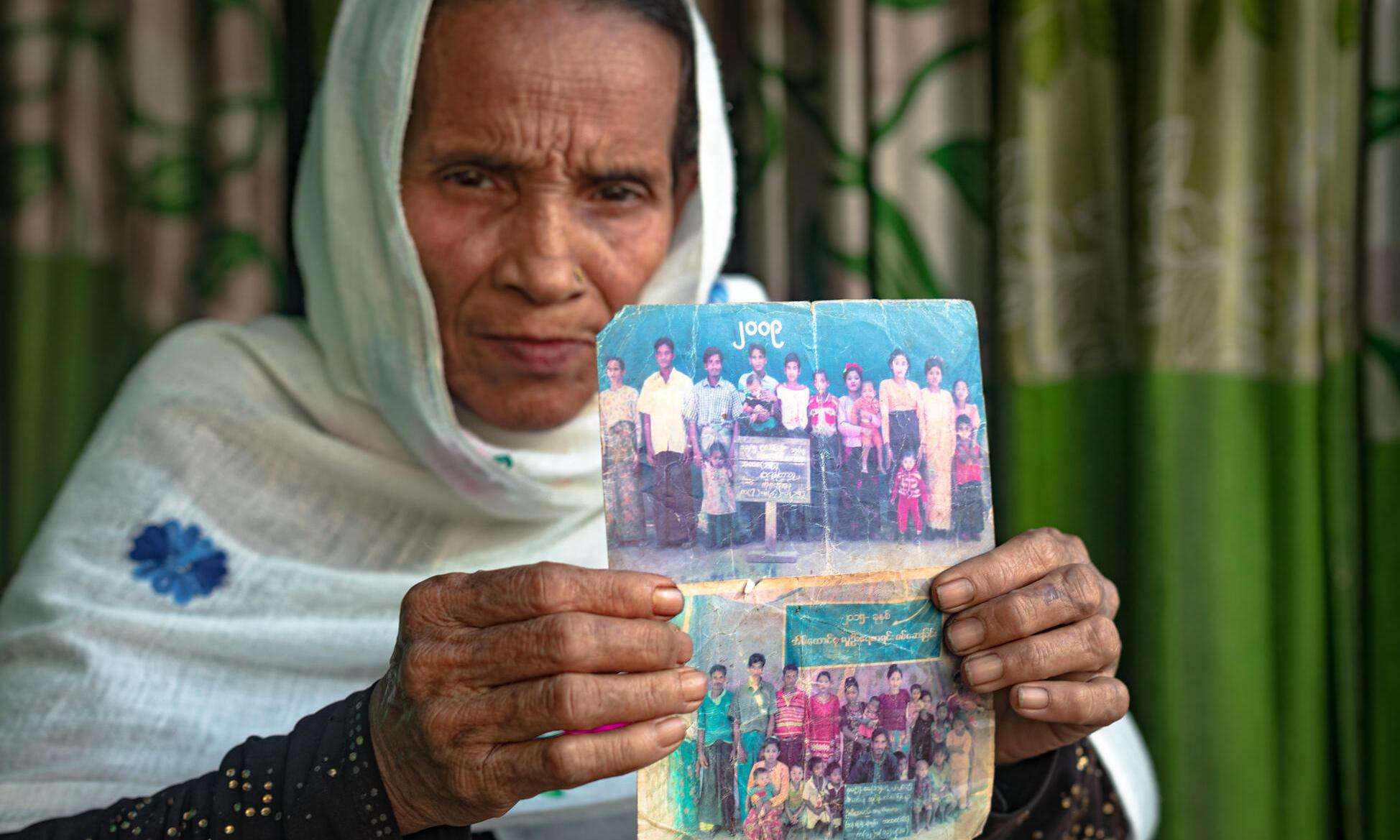

"In the urgency of it all, I grabbed my daughter's birth certificate and a family photo," she said. "I even left behind clothes that I had freshly washed."

Melua's chosen mementos are pragmatic. The items are not only a part of her family's history but important documents that could potentially determine their fate as refugees forced from home.

When Melua fled Myanmar, she took a few family photos and a household registration card used to confirm nationality. Bangladesh 2023 © Mohammad Hijazi/MSF

She remembers life in Myanmar with vivid clarity: the pillars of her home, the stretch of land she owned and the fence around it, the chickens and her favorite spot for meals. Any mention of her homeland stirs up emotions.

"It's hard to talk about it without shedding tears.”

Despite her nostalgia, Melua said she wouldn’t return without certain conditions being met.

"For us to consider going back, there has to be an assurance of safety, non-discrimination, citizenship rights, and opportunities for the next generation—especially access to education," she explained. It's this hope for a brighter future for her children that drives Melua's spirit forward.

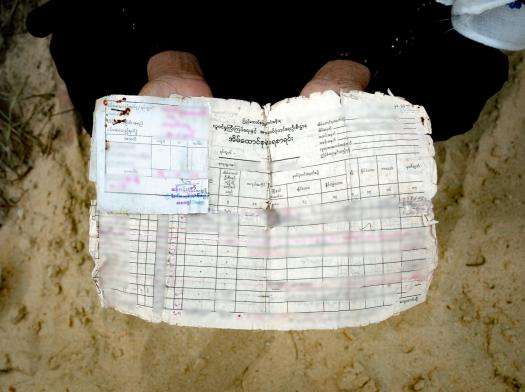

Two months before the violence in Myanmar escalated in 2017, the threat of widespread arrests forced Salamatullah to make the difficult decision to flee. He left many of his belongings behind, but managed to take a few family pictures, a court document, a blanket, a tiffin food container, and a basket to carry what was left of his former home.

"These items were all I could gather in time," he said. "The pictures, especially, gave me a source of strength during those two days [fleeing]."

Salamatullah's basket held a blanket, a food container, and his official documents, including documentation of his release from prison in Myanmar. Bangladesh 2023 © Mohammad Hijazi/MSF

The court document tells a story of its own. "I had to pay a fine to secure my release from prison," he explained, referring to an arbitrary sentence he faced in Myanmar. "It's a testament I carry, highlighting the challenges we sometimes endure without just cause."

While Salamatullah made his journey alone, his wife, Subitara, undertook a separate journey with their three children. They reunited at the refugee camp in Cox's Bazar.

"With each day, I'm getting older, and everything remains so uncertain," said Salamatullah. "What keeps me up at night is thinking about my children's future in these conditions. More than anything, I want them to have a chance at a good education and their rightful freedoms."

A father of two daughters and four sons, Habibullah worked as a driver back in Myanmar, ferrying passengers from street to street. Life was stable until 2017 upended normalcy as he knew it.

When violence surged, it was ordinary civilians like Habibullah who found themselves caught in the turmoil. "Our villages became targets," he said, heavy-hearted. "Staying there was no longer safe. We were left with little choice but to flee or risk our lives."

With only a few days to make a life-altering decision, Habibullah and many of his neighbors sought temporary safety in the mountains as the intense fighting encroached on their homes.

"The journey took us to the river on the border with Bangladesh, nearly 50 miles away," said Habibullah. "As we hid, trying to stay safe, the haunting sound of distant gunshots was a reminder of the dangers around us." The chaos separated many families, but they were later united at the refugee camp.

Habibullah managed to hold onto valuable documents and his driver's license from Myanmar. "In these testing times, this is my proof of identity," he said, knowing the documents would be crucial in establishing roots and security in unfamiliar surroundings.

"If the situation improves in Myanmar, I will definitely return," he said. "Who wishes to leave their country? Who desires to be stateless, without any recognition? I miss everything about Myanmar—my family, my yard, my cattle, my home, and the graves of my parents."

MSF's response to the Rohingya refugee crisis

Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has been working in Bangladesh since 1985 and in Cox’s Bazar since 2009, and established the Kutupalong field hospital to serve refugees and the local community. As mass numbers of Rohingya refugees arrived in Bangladesh following the events of August 2017, MSF scaled up operations in response. The focus has since shifted to long-term health care, addressing chronic illnesses like high blood pressure and diabetes.