A resurgence of violence between armed groups in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has displaced more than 1.6 million people over the last two years, in a region already devastated by 30 years of conflict.

For two years, the armed group M23 (March 23 Movement) has been fighting the Congolese army and its allies in North Kivu province, and the violence began to intensify in late January. Now, the fighting has reached the border with South Kivu province.

This new escalation of the conflict has once again caused entire communities to flee. In just the first week of February, armed clashes forced over 70,000 people to flee to South Kivu and 200,000 people to Goma, where more than half a million displaced people had already settled over the past two years. New informal sites have sprung up, while existing sites have grown more crowded, with living conditions that fall far short of humanitarian standards.

The current situation has raised major health concerns. First, the influx of newly displaced people arriving in Goma is exacerbating the critical health situation and urgent needs in camps and increases the risk of epidemics, especially cholera. In addition, the proximity of the fighting is increasing the physical risks people face. Finally, the fighting around Goma makes it difficult to provide vital humanitarian support to remote areas of North and South Kivu, where the needs are also massive.

Abdou Musengetsi, deputy medical coordinator with Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), breaks down what’s happening in eastern DRC and what it means for people impacted by the violence.

How is this new outbreak of violence impacting people in the region?

In recent weeks, violent clashes in Masisi territory of North Kivu have led to a new exodus around Sake and towards Goma, the provincial capital. In just 10 days, nearly 250,000 people fled the fighting. They are now sheltering with host families and in pre-existing, unofficial displacement sites—as well as new ones—mostly to the west of Goma.

In these sites, families are crowded into makeshift shelters that offer little to no protection from the rain. Every day, people tell us it is a struggle to get enough food and clean drinking water—often going without. Hundreds of people are forced to share just one toilet and they have nowhere to wash. One woman who recently fled to Goma told us how she left with nothing but her children and the clothes on her back. She was forced to flee several times as the conflict spread, and now she lives in the camp, suffering every day, but has no option to return home as it is too unsafe.

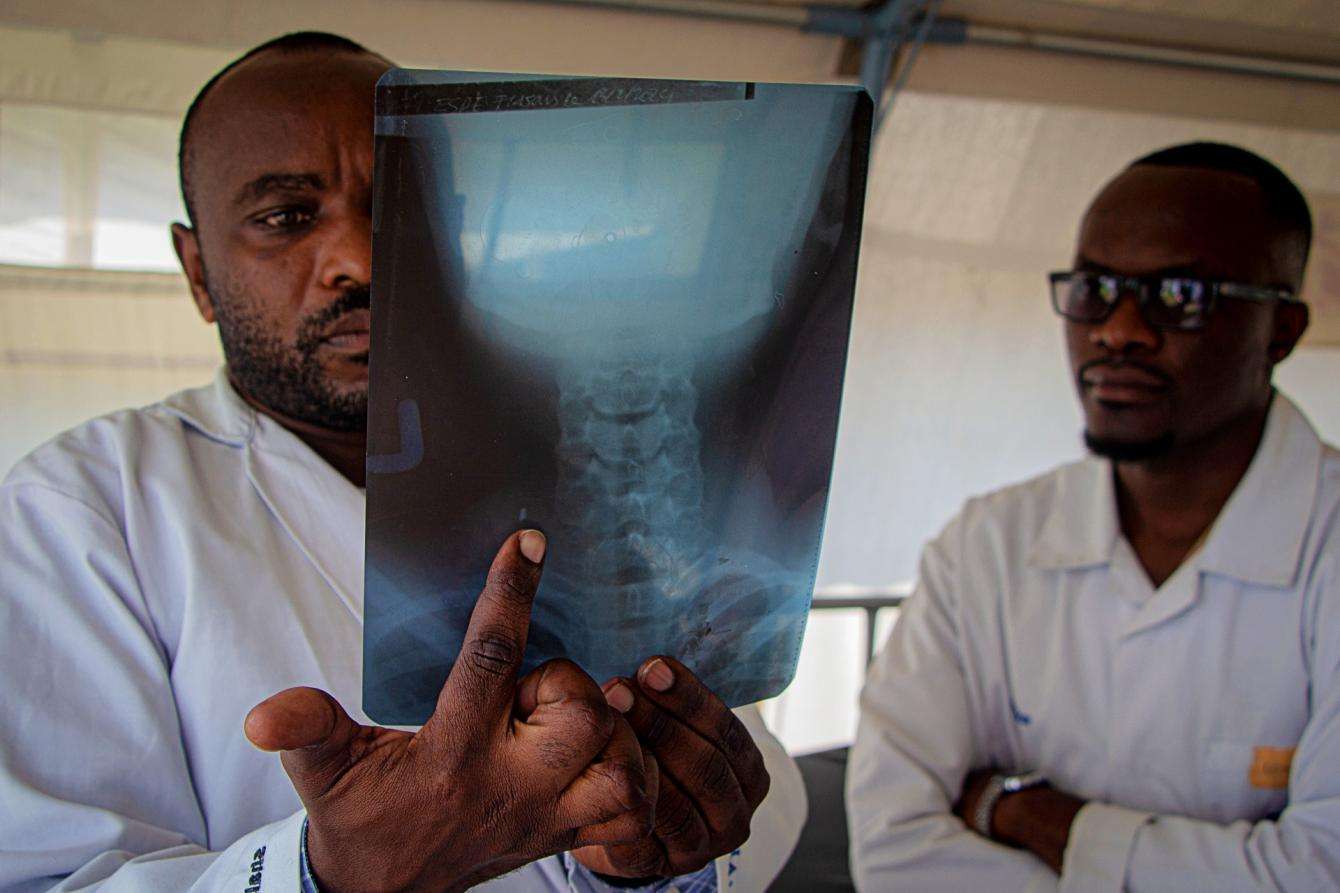

Meanwhile, the two MSF-supported hospitals and several MSF-supported health centers in Masisi territory have received influxes of war-wounded patients. Over the past two months, MSF teams in the Ministry of Health-run hospital in Mweso have treated around 146 war-wounded people, mostly for gunshot wounds and injuries from explosions. But the main access roads to the north, west, and south of Goma are inaccessible due to the insecurity and fighting, so it is extremely challenging to get supplies to these facilities. This has also severely hindered humanitarian and medical access to hundreds of thousands of people in the Masisi territory.

In parallel, fighting on the border between North and South Kivu has caused tens of thousands of people to flee mainly southward, toward the city of Minova, which was already hosting many displaced people. People are sheltering wherever they can, in schools and dozens of different sites.

Some of the health structures we support in the region have been overwhelmed with an increased number of patients suffering from illnesses related to the deterioration of their living conditions. We are also seeing more cases of sexual violence and war-wounded [people]. The hospital in Minova has received over 167 injured patients since February 2, including several women and children.

In one single day, on March 7, the health staff received 40 injured people, and seven others were dead on arrival. Patients are forced to share beds and staff work around the clock with limited resources as bullets fly very close—the frontline is just five kilometers [about 3 miles] away.

What are the main health concerns?

At the health level, we fear a flare-up of diseases again—in particular, cholera, as fighting has forcing thousands to settle in overcrowded and unsanitary sites.

Combined with the lack of access to clean water, this is creating the perfect conditions for the spread of cholera. We have already been dealing with cholera in some of the camps for months, so with the new influx of people arriving it is likely to exacerbate the existing outbreak.

Before the resurgence of this conflict, the health situation in these two provinces was already dire due to low vaccination coverage among children under five years of age. Coverage is the lowest in around 30 years, according to the World Health Organization. Poorly functioning health structures—notably due to shortages of medications and a lack of trained health professionals—also contribute.

MSF teams have supported the local authorities in responding to recurring epidemics of measles and cholera, which spiked last year after peaks of mass displacement. We also provide support to help increase access to general and specialized health care, particularly in more remote health zones such as Masisi, Mweso, or the Hauts Plateaux of the Minova health zone.

How is the instability increasing health risks like cholera?

Cholera is not a new disease in eastern DRC. It is endemic, and sporadic cases are regularly reported and treated. However, the situation is now extremely concerning due to the high number of people living in overcrowded displacement sites for the last 18 months, where the level of hygiene and sanitation, as well as safe drinking water, was clearly inadequate even before the recent arrival of hundreds of thousands of newly displaced people.

The increase in cholera cases is directly linked to the lack of hygiene and a lack of access to safe drinking water and sanitary facilities such as clean latrines and showers. This disease can be fatal if not treated in time. Children are the most vulnerable and can die from cholera in just a few days. Depending on the severity of their illness, most patients need rapid oral or intravenous rehydration, but some people can be treated in the community by setting up oral rehydration points.

In recent months, MSF teams have treated thousands of patients for cholera in displacement sites in and near Goma. In the first two months of this year, 75 percent of the over 1,000 patients MSF treated at our health center in Bulengo displacement site and Sake health center had just arrived and had no access to clean water, latrines, or hygiene products such as soap, while living in close proximity to other people. In the space of a few days, the population [of Bulengo] increased by 50 percent. These factors clearly contribute to the rapid spread of this highly contagious disease.

What is MSF doing to prevent a cholera outbreak?

In response to the complete lack of potable water, last year MSF built a water pumping and chlorination station on the shores of Lake Kivu that pumps and disinfects up to two million liters of potable water every day. We also distributed hundreds of thousands of gallons of potable water per day to the displacement sites, as well as constructed latrines and showers. Yet this is an emergency response and it is not enough to meet the needs, even more so with the new arrivals. It is urgent that other humanitarian organizations and Congolese authorities urgently respond with additional water trucking [distribution] and building more emergency latrines.

While we continue to vaccinate and treat patients for cholera—over 20,000 patients were treated in North and South Kivu in 2023 alone—if hygiene conditions do not improve, then our medical response will have little impact. Given the scale of the needs today, and the number of people living together in precarious conditions, we fear that cholera will spread very quickly, and that MSF alone will not be able to treat all the patients who become ill. Other humanitarian organizations need to step in urgently to avoid a health catastrophe.