Amro, Mohamad, and Mahmoud are among the 36,000 people who were injured during the “Great March of Return” protests. These demonstrations were held near the security fence between Gaza and Israel every Friday between March 30, 2018 and December 2019, to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the 1948 Palestinian exodus, an event known to Palestinians as the “Naqba.” Muawiyah was injured during the 2021 bombing of the Gaza Strip by Israeli forces. Like 152 fellow Palestinians, all of them underwent amputations to prevent the risk of infection in their wounds.

They were photographed by Giles Duley, who lost two legs and an arm after stepping on a mine in Afghanistan in 2011. “I'm a photographer, a chef and a writer, but I'm an amputee myself. Their stories resonate in a very personal way.”

During the 2018–2019 protests, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) tripled its medical capacity to care for the injured, offering plastic and orthopedic surgery, as well as treatment for bone infections resulting from the wounds. We also provided post-operative follow-up, including dressing changes, physiotherapy, pain management, and psychosocial support. From the first demonstration on March 30, 2018, to November 30, 2019, MSF hospitalized more than 4,830 people in its trauma units.

Four years after the protests began, many patients are still dealing with the devastating consequences of their injuries, which have taken an increasingly heavy toll on their lives and those of their loved ones. For many, the severity of the injury makes amputation inevitable.

“If you don't get an amputation when you should, your body ends up fighting a chronic infection like cancer,” said Herwig Drobetz, an MSF surgeon in the limb reconstruction unit at Al-Awda Hospital These patients look really sick. They are usually tired and malnourished. Once they are amputated, they are different people. They feel better, it's amazing how quickly they get better.”

But patients and their communities often view amputations as “failures.” Some people, especially young men, refuse the procedure and endure years of chronic pain, repeated operations, and reduced mobility in order to keep the impacted limb.

Duley understands this from personal experience. “As an amputee myself, I have had many conversations with people who are dealing with the idea of losing a limb and the psychological challenges that precede the surgery,” he said. “For young men, there are several reasons for this hesitation. Fear of not being able to work and provide for their families; stigma and perceived shame at this new body image. Patients have told me that they feel they are no longer ‘real men’ or that no one will like them. I understand these concerns. But if you put prejudice aside with the support of those around you, a normal life is entirely possible. We need to make these positive stories visible and fight the stigma.”

Amro Ayman Alhadad, 23, was injured by an Israeli army bullet on May 14, 2018, during the “Great March of Return.” Along with some of his classmates, he had joined the demonstration prompted by then-US President Trump’s decision to move the US Embassy to Jerusalem.

His bus arrived at the demonstration site at 11:15 a.m. Fifteen minutes later, he was shot in his leg and lost consciousness.

That day, according to health authorities in Gaza, 52 Palestinians were killed and 2,400 injured. In the chaos, Amro was initially presumed dead. It was pure chance that a neighbor who works as an ambulance driver saw him among the bodies and realized he was still alive.

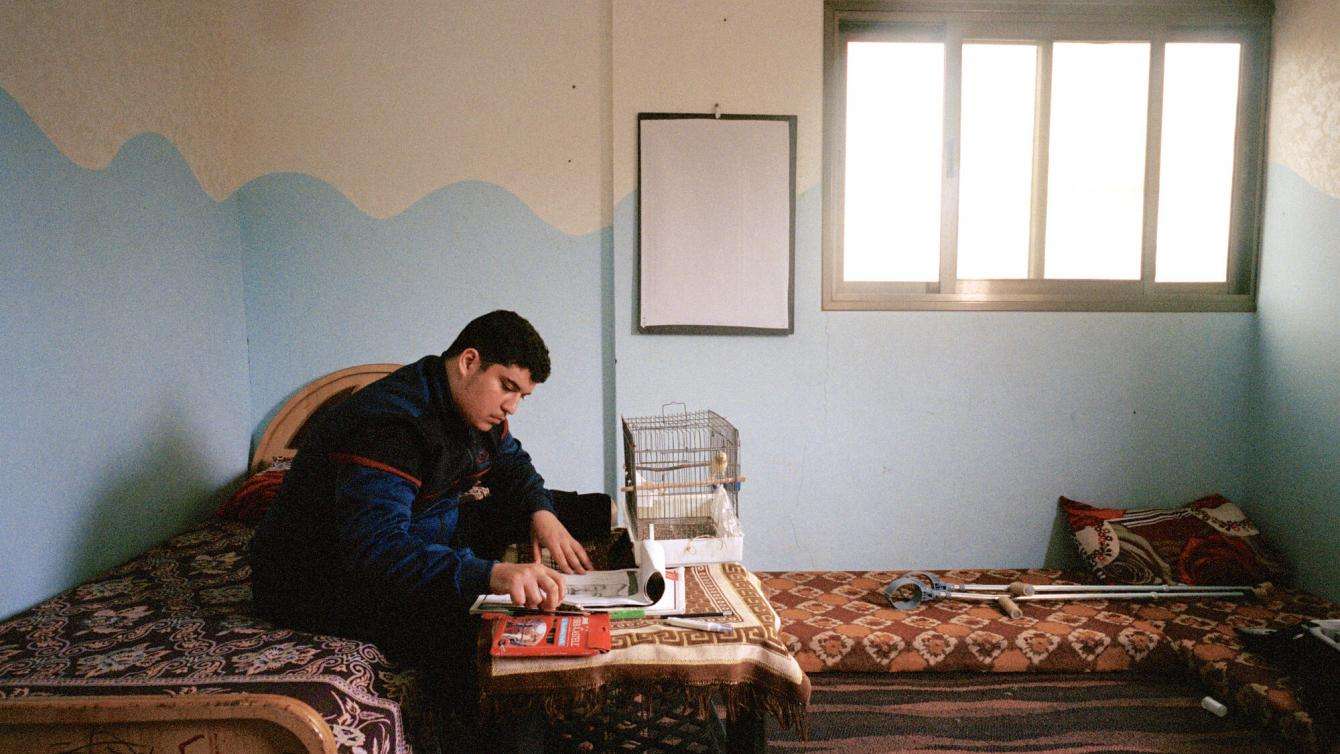

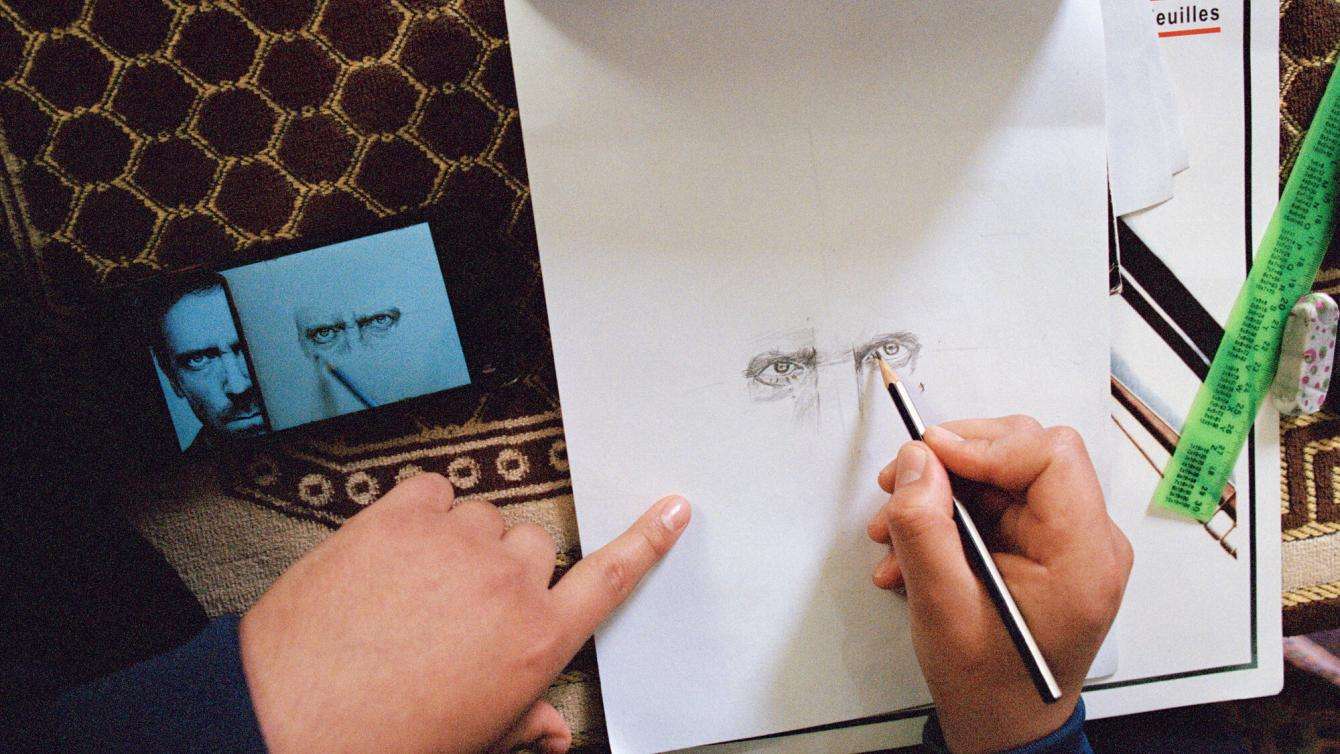

After receiving emergency treatment in Gaza, Amro was taken to Turkey for more surgery, where his leg was amputated. Upon his return, Amro locked himself in his family's apartment in Gaza City.

“I found escape in drawing, I watched videos online and taught myself to be an artist,” he said. He spent his days indoors, drawing and taking care of his bird, which never leaves him. After losing his leg, Amro feared crowds and how he would be viewed by people.

Mohamad Saad was injured in September 2018 after rushing to the border fence upon learning that his fifteen-year-old son had been injured. Moments after finding his son, Mohamad was also shot in the leg by Israeli forces. When he regained consciousness, he was told that he might lose his leg due to a blood clot.

Over the next few years, he underwent ten operations to stabilize the condition of his leg, but he was unable to walk. He was in pain 24 hours a day and became increasingly frustrated about being unable to work.

In 2021, Mohamad had his first consultation with the MSF team, who recommended amputation. He quickly accepted, determined to move forward. “Fortunately, I have not felt any stigma,” he said. “My wife and family have shown me love and encouragement throughout. My wife is definitely the main reason I accepted the amputation and the challenges that come with it.”

Mohamad openly discusses his experience as an amputee. “If doctors advocate amputation, I would recommend doing it. Before I did, I couldn't go outside or play with my children. Now I can do everything. After three years of pain, I can finally get on with my life.”

On May 12, 2021 Muawiyah Al-Wahidi, 42, was opening his barber shop in Gaza City when a rocket hit a car in the street. He was not hurt, but the tailor working across the street ran towards him, shouting that he had been hit in the chest. Halfway to Muawiyah, he collapsed, blood pouring from his mouth.

Muawiyah was crouching next to him reciting prayers when the next rocket hit. When he woke up in the hospital, his right leg had been amputated and his left ankle was broken.

In the weeks that followed, he refused to eat and suffered from depression. “I would look at myself and then look at others and said to myself, I don't want to be different,” he said. When he returned home from hospital his depression got worse. “At first I refused the food my wife cooked, it was hard for her. I was angry at her, at my brother, at the kids. It was hard. But fortunately, we got through it.”

Community support played an important role in his journey. So did the guidance of Marwah, an MSF psychologist, who taught him and his wife Yassmin how to deal with anger and depression.

Mahmoud Khaled Ibrahim Khader, 27, had his leg amputated after he was shot in the thigh in May 2018.

He was initially transferred to a hospital in Jordan where surgeons attempted to save his leg. After 38 days, with no signs of the bone healing, the decision was made to amputate. Further surgery followed, but a prosthesis could not be used because the wound remained infected.

In July 2020, two years after losing his leg, he met an MSF medical team, who suggested a new amputation. The team believed that removing an additional five centimeters of bone could reduce the infection and create a more stable stump that would be better suited to a prosthesis. Almost immediately after the surgery, Mahmoud could feel the difference. Soon enough, he could wear a prosthesis and was able to return to work.

Nevertheless, he is still worried about stigma, such as the idea that amputees are more likely to become drug addicts. “My girlfriend's parents refused to let me marry their daughter,” he said. “They said, 'You're on tramadol, we don't want our daughter to marry a drug addict.’ That was hard to hear, even my best friend thought that.”

It was a chance encounter with a group of amputee cyclists that helped Mahmoud finally find peace. He can now both release his energy and spend time talking with people who share a similar experience. “Cycling became my escape, and through this activity people could see that I was athletic and not on drugs.”

A week before meeting Giles, Mahmoud got married. Today, he dreams of starting a family. “But,” he said, “cycling will always be a part of my life. This group is also my family.”