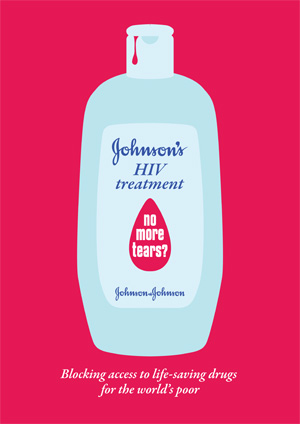

Pharma Giant?s Refusal to Participate in Patent Pool Undermines Access to Key AIDS Drugs

New York, NY, April 25, 2011—Pharmaceutical giant Johnson & Johnson is putting the lives of people living with HIV at stake by refusing to participate in the Medicines Patent Pool, a mechanism designed to lower prices of HIV medicines and increase access to them for people in the developing world, said the international medical humanitarian organization Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) today.

Johnson & Johnson, which holds patents on three key new HIV drugs desperately needed throughout the developing world, has so far refused to license these patents to the Medicines Patent Pool. The Pool has been set up to increase access to more affordable versions of HIV drugs, including fixed-dose combinations that include multiple medicines in one pill, and to develop much-needed pediatric HIV drugs.The Pool would license patents on HIV drugs to other manufacturers and the resulting competition would dramatically reduce prices, making them much more affordable in the developing world. However, since the Pool is voluntary it will only work if patent holders like Johnson & Johnson choose to participate.

“High prices mean patients in poor countries continue to be relegated to second-class care, with no choice but to take older, more toxic drugs we would no longer use in the U.S., and with almost no treatment options when the virus becomes resistant to the limited number of drugs available,” said Sophie Delaunay, executive director of MSF-USA. “By putting its HIV drug patents in the pool, Johnson & Johnson has a unique opportunity to transform this situation and save lives worldwide. Instead, it has chosen to turn its back on these patients.”

Johnson & Johnson holds patents on HIV medicines rilpivirine, darunavir, and etravirine. Rilpivirine is a promising antiretroviral (ARV) under development for use in first-line treatment regimens. Darunavir and etravirine are important for patients who have developed resistance to their existing treatment.

Even at Johnson & Johnson’s so-called reduced “access” pricing, the cost of these drugs is prohibitive; darunavir is priced at $1,095 per patient per year, and etravirine at $913 per patient per year in the world’s least-developed countries, most of which are in sub-Saharan Africa. Many developing countries have to pay even higher prices.

In December 2010, the National Institutes of Health, which holds the intellectual property rights for a manufacturing process for darunavir, put its patent for the AIDS drug in the patent pool. Johnson & Johnson holds the drug’s remaining patents, and is effectively blocking other companies from manufacturing and making darunavir available at prices affordable for patients in the developing world.

There are now more than six million people receiving lifesaving ARV treatment worldwide. This would have been impossible without competition from generic companies that helped bring prices down from $10,000 per patient per year for the most commonly used first line regimen, to less than $100 per patient per year. Today, mechanisms in international law and additional voluntary initiatives such as the Medicines Patent Pool will be crucial to ensuring that patients have access to newer, less toxic medicines to keep them alive. Several drug companies have already begun negotiating with the pool.

MSF now provides treatment to more than 170,000 people living with HIV worldwide, and is beginning to witness the inevitable, natural phenomenon of treatment failure, in which patients everywhere develop resistance to treatment and need to graduate to newer regimens. This is happening now in MSF’s longest running HIV projects, in South Africa, Mozambique, Kenya, and Cameroon.

“We have patients who have no other treatment options other than Johnson & Johnson’s darunavir, which is so expensive that the South African government cannot afford it,” said Dr. Gilles van Cutsem, medical coordinator for MSF programs in South Africa and Lesotho. “MSF is now paying for these drugs, but this is just the beginning of the problem. Ten years after we put the first patients on antiretroviral treatment, we now have patients in our clinics who have become resistant to drugs available at affordable prices. We’ll soon be back in a situation where we’ll have to say there are drugs in the private sector, or in rich countries, that could treat you, but we cannot afford them.”