This article is part of the Fall 2018 issue of Alert that highlights the urgent medical aid our teams provide to people on the move through Central America and Mexico.

Mexico City

Those who make their way through Guatemala and into Mexico do not find any guarantee of safety.

As the number of people fleeing violence and poverty in the Northern Triangle grows, the Mexican government has clamped down on the country’s southern border, with support from the US. Police and military surveillance and law enforcement, coupled with widespread corruption and suspicion of collusion with cartels and maras operating in the southern Mexican states of Oaxaca, Veracruz, and Tabasco, have resulted in an atmosphere of lethal violence and lawlessness.

MSF teams provide primary health care and psychosocial services along the migration route through Mexico, treating patients at the La 72 migrant shelter in Tenosique, at the FM4 shelter in Guadalajara, and, via mobile clinics, at the Casa del Migrante shelter in Coatzacoalcos. These sites serve as oases of sorts for people making the dangerous journey north. But as violence near the border with Guatemala and along the migration route has escalated, it’s become clear that some patients have greater medical needs. People who have been exposed to extreme violence—torture, kidnapping, rape, psychological abuse—require comprehensive, specialized, and integrated care.

MSF in Mexico in 2017

In Mexico City, far less affected by the violent crime plaguing other parts of the country, MSF is trying a new approach. In the Colonia Guerrero neighborhood, northwest of the city’s historic center, MSF opened the Center for Integral Action, known by its Spanish acronym, El CAI, in July 2017.

El CAI lies behind a nondescript gray metal sliding door on a residential street, without any identification that might attract unwanted attention. Through the door, past a volleyball net strung up across a concrete courtyard, is a lot surrounded by dormitories painted a pale, soothing yellow. Once inside, the sounds of the city fade, giving way to an atmosphere of hushed peace.

The calm belies the severity of the wounds, both physical and mental, that are being treated here. Referred to the center from other MSF projects in Mexico, the UN Refugee Agency, and Mexican nongovernmental organizations, the patients at El CAI have been through horrific journeys.

“We see similar situations here for people on the move as we do in war situations like Syria or Yemen,” explains MSF psychologist Diego Falcón Manzano. Criminals along the migration route often use psychological torture when seeking to kidnap or extort victims or forcibly recruit new gang members. “Before, on the journey, you were either beaten or raped. But now … they don’t just beat you, they make you see how it’s done to other people. Or they make you kill someone or handle human body parts.”

Physical wounds can be mended, but mental injuries can take a long time—and hard work—to heal. In addition to a gymnasium, meals, and 24-hour medical monitoring, patients living at El CAI receive psychotherapy and social services to help them rebuild their lives. “We teach patients to strengthen their capacity to decide how they’re going to live their lives,” says Manzano. “To save money or find a job. We help them to make a plan for life after leaving El CAI in both the medium- and long-term.”

“We care for people without a timetable,” says Manzano. “They are here for as much time as they require.” Residents at El CAI, which has a 28-bed capacity, have stayed for as little as three weeks and as long as a year. In the roughly one year that the facility has been open, staff say the treatment success rate has been around 80 percent. Patients who leave receive follow-up care and can continue to access the facility’s services on an outpatient basis. Some remain in Mexico to work, attend school, or wait on asylum claims. Others resume their journey north.

Reynosa

On the banks of the Rio Grande, in the Mexican state of Tamaulipas, lies the border city of Reynosa. Home to more than 600,000 people, Reynosa is a common way station for many Central American migrants hoping to gain entry to the US. It’s also one of the most violent cities in Mexico, convulsed by conflict between criminal cartels vying for territory.The presence of Mexican military police in the streets does little to ease the tension, which takes a heavy psychological toll on both permanent residents and migrants passing through.

“If you scratch the surface a bit, everyone here in the city has been a victim of violence, either directly or indirectly,” says MSF psychologist Violeta Elizabeth Perez Quintero. Here, MSF teams provide medical and psychological care, along with social services, to both local and migrant communities. A team comprising a doctor, nurse, social worker, and psychologist work at a fixed clinic, while mobile teams visit two migrant shelters, Casa del Migrante Guadalupe and Senda de Vida, in addition to a shelter for minors, Centro de Atención al Menor Fronterizo (CAMEF).

It’s nearing 100 degrees Fahrenheit under a cloudless mid-July sky when the MSF mobile clinic team arrives at the Senda de Vida migrant shelter on the bank of the Rio Grande. Founded in 2000, this Christian shelter has grown from a single house to a modest compound, and more housing is under construction. With little national funding available to aid people on the move, and absent an international response commensurate with the scale of the displacement crisis in Central America, Christian groups and small, local nonprofits have stepped in to fill the wide gaps in services. MSF teams have been providing mental, social, and physical health consultations to the migrants sheltering here for around a year and a half.

Thirty-two-year-old Piedad waits in the blistering heat in the complex’s concrete courtyard with her three-year-old daughter, Dayli. The girl has been suffering from an ear infection, so Piedad has brought her to see one of the MSF doctors. Her three sons—15-year-old Josue, eight-year-old Eddy, and seven-year-old Jairo—kick a soccer ball back and forth in the shade of one of the shelter buildings.

“I used to run a bakery in Triunfo de la Cruz, Honduras,” says Piedad. “But we were told by the maras that we had to pay the ‘war tax.’ We couldn’t afford to pay anymore—we only sold bread. My son, Josue, was threatened. We were told that if we couldn’t pay we would be killed.” Piedad, her husband, and their children felt they had no choice but to flee their home, which they did on April 15. They set off on foot for the Guatemalan border in hopes of reaching safety in the US.

Eventually they caught a bus to Tenosique, Mexico, where they were assaulted and robbed of their identification documents. They found shelter at La 72. “We saw MSF in the migrant shelter in Tenosique,” says Piedad. “They gave us counseling and medicine for my children, and medical care and advice.” From there they continued on the path north, walking and catching buses where they could. “In some cities we had to beg for money to buy bus tickets or food,” she says. “We slept in the hills or on the outskirts of towns. There were days when we didn’t eat or drink any water.” They stopped in Coatzacoalcos, where they again received care from an MSF team.

Finally, they reached Reynosa, where they sought out Senda de Vida, which they had learned about on their journey. They had also heard that they might have better luck crossing the border if they traveled separately, with Piedad accompanying her sons and her husband accompanying Dayli. So Piedad set off with the boys, heading for the bridge over the river while her husband and daughter remained at Senda de Vida.

“It was a terrible experience,” she remembers. “We first met with US immigration and asked for refugee status. But we were denied, and they told us to wait. We stood in the sun for four hours. Finally, Mexican immigration agents came and asked if they could take us. The Americans said yes.” Without the papers that had been stolen in Tenosique, Piedad could not prove who she was or where she’d come from. She and her two younger sons were brought back to Reynosa and held in a jail cell. Josue, her eldest son, was held separately in a detention center for minors. She had no idea where he had been taken, or what had become of him, for seven days.

Finally, on the eighth day, Mexican immigration officials reviewed Piedad’s one remaining document, a paper from the consulate that proved the family had planned to apply for a humanitarian visa in Mexico. She was released and reunited with her family at Senda de Vida. They have now been living at the shelter for two months, essentially stuck in limbo. Returning to Honduras is impossible, but the prospects of making it to the US grow dimmer by the day.

“I know we can’t be here forever,” Piedad says. “I’m the cook here now. And my husband has day jobs, but he only makes 150 pesos a day [about $8]. That’s nothing. We can’t find a place to live, we can’t send our kids to school. I just want a better future for them.” The family has been working with a legal counselor here at the shelter, but there aren’t many options available for people in their position. A Mexican humanitarian visa would allow them to stay in the country but would complicate finding work there. “Right now I don’t know what we’ll do next,” she says, shaking her head. “But my idea is still to cross to the US.”

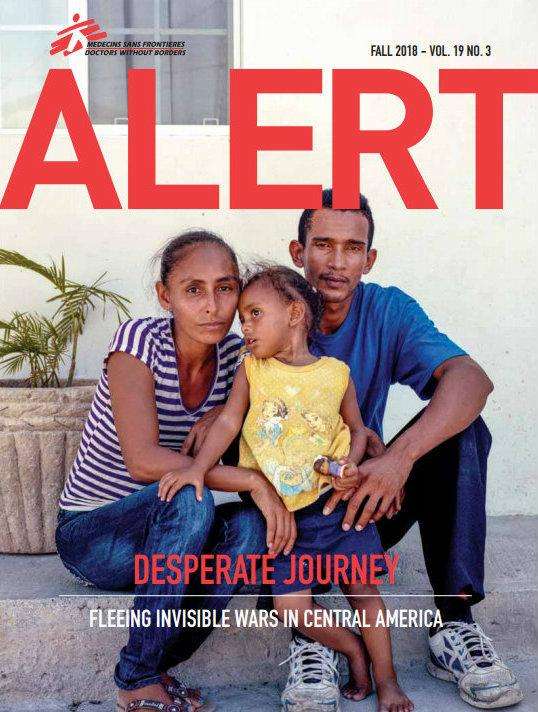

On the opposite end of the compound, another family sits on the concrete steps of Senda de Vida’s administrative building, where MSF has installed a small clinic the mobile team uses for consultations. Ruth, Carlos, and their two young daughters arrived eight days ago from Catacamas, in Honduras’s Olancho department. They too find themselves trapped here in Reynosa after being denied asylum at the US border.

“I was kidnapped in Honduras,” says Carlos. “Thank God, I escaped, but they wanted to kidnap my daughters and wife as well.” He says they did not even need to think about the decision to leave: “We were in danger.” They were aware there could be further risks along the way. “We came to Mexico by bus,” says Carlos. “We went through Guatemala, but it’s difficult to go through there, too. Getting into Mexico is even worse. There are kidnappings, rapes . . .”

“We’ve suffered so much in Mexico,” says Ruth, stroking her daughter’s hair. “We stayed in the bus station, sleeping with our kids. There were times when we didn’t have anything to eat.” Ruth and Carlos don’t know where they will go from here, but they know it won’t be back to their home country, where the rest of their extended family still lives. “We can’t live in Honduras,” Carlos says flatly. “I’d like us to have a home of our own, but it was necessary to leave there. They threatened my children.”

The family has a temporary permit to stay in Mexico and can be referred to legal aid through MSF’s psychosocial care program. But their future here, stuck between a home they can’t return to and a haven closed off to them, remains desperate. “I think the United States needs to listen to what people are going through,” says Carlos. “Narcotrafficking, kidnapping, gangs—people are dying in Honduras.” He knows that some people may be crossing the border to find work or, as he says, “just to check it out.” But for Carlos and his family, the painful decision to leave was forced on them. “Only we know how we feel. Only we know what we’ve been through.”