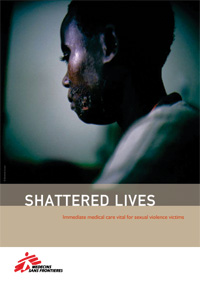

Coming Out of the Dark with Seruka

Burundi 2008 © Benedicte Kurzen/VII Mentor

“I came back from school, I had lunch and was getting ready to go out again. My father offered me 150 francs to come to the bedroom with him. I said I didn’t want to go. But then he took me to the bedroom by force and did bad things to me. It was the second time he did it. The first time I didn’t tell anybody. I was afraid. This time I decided to tell my mum because it hurt really, really badly”.

Read the full report:

Shattered Lives

In a country where the language does not have a word for rape, MSF is helping victims of sexual violence come forward for care. Seruka – which means ‘coming out of the dark’ in Kirundi, the national language of Burundi – is the name of the MSF clinic for rape victims in Bujumbura, the capital. MSF opened Seruka in 2003, after medical teams working in its centre for war-wounded people observed an increasing number of rape victims amongst patients. An assessment showed that although sexual violence was a common phenomenon, medical care for rape victims was not available. To date, the MSF team working in Seruka has seen almost 7,000 victims of sexual violence. By mid-2009, the center will be taken over by ISV (Initiative Seruka pour les Victimes de Viol), a Burundian association formed by staff working in the center.

Despite the peace agreements that marked the end of the conflict in Burundi in 2005, sexual violence persisted. The return of refugees and the displaced, the presence of high numbers of demobilized soldiers, lack of economic opportunity, degradation of social norms and the predominance of female-headed households are all thought to have contributed to the high levels of sexual violence.11

Official data about rape in the country are non-existent. talking about sexual violence in Burundi is taboo and silence often prevails. Rape brings shame and humiliation to the whole family and their attempts to redress it are unlikely to bring relief to the victim. as a consequence, few people seek medical care after a rape and even fewer press charges against their perpetrators. “It is very difficult for women to reveal they have been raped. Society often does not recognize the victims as a victim. victims are accused more often than the perpetrators”, said Luk van Baelen, MSF project coordinator in Seruka.

In some cases, practices that would be considered rape in western societies are traditionally accepted by Burundian customs and fostered by cultural myths. Some physically or mentally disabled women are raped because some men believe that this will generate wealth, for example. A traditional healer may direct a man to rape a child, telling him that doing so will solve a problem the man faces.

The judicial system is largely indifferent to sexual violence. Courts often refuse to hear rape cases without a witness, which forces most victims to give up on pressing charges. Sometimes, medical-legal certificates, which can be used as evidence in court, are rejected unless they are signed by a government doctor. to obtain a signature, a victim must pay up to 15,000 francs (15 USD), which is unaffordable for many Burundians. “The justice system is very difficult. It takes too long. It may be two or three years, if you are lucky, before the aggressor is brought to court. and it doesn’t repair the damage that rape has caused. Many victims simply choose not to seek justice”, said Joseph Mugigi, a staff member of a Burundian human rights organization that offers legal support to rape victims, called Ligue Iteka. As a result, rape in Burundi often remains secret, untreated and unpunished.

The law in Burundi is changing. It will include a more precise definition of sexual violence and require tougher punishment for aggressors. “But without a special court for sexual violence and the support of forensic evidence to persecute aggressors, applying the law will be difficult”, said Mugigi.

A Specialized Clinic for Victims of Sexual Violence

Seruka Center is open 24 hours a day, seven days a week, to provide emergency and follow-up care for victims of sexual violence. Although most patients come from the capital Bujumbura, Seruka attracts rape victims from all over the country.

Patients are first seen by a nurse at the triage area, where little is asked about the rape. “There is not enough privacy in this area. And we don’t want to make the patients tell their story lots of times”, said Gloriose Nyakuza, an MSF nurse. “Here we just try to identify whether they are coming for a different reason, unrelated to sexual violence. in these cases we refer them to another health facility”. at the triage, patients receive the first dose of antiretrovirals to prevent hiv, part of their post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) treatment. “HIV is the biggest concern for most of our patients”, Nyakuza said. “There is no time to be wasted, the sooner they receive PEP, the better. They also feel relieved after they’ve taken the tablets and more at ease for the consultations. Later, if the doctor decides that there was not a risk of contamination, then they will not take the full course of PEP”.

A team of psychologists helps patients deal with the trauma of rape and prevent psychological disorders that commonly arise from it. “ Apart from fear of HIV, they are normally terrified about becoming pregnant”, said MSF psychologist, Joel Montanez. “They also have a very strong feeling of dirtiness and they wonder if they should tell anybody about the rape. They have flashbacks, difficulties sleeping and are afraid of being ostracized in their communities”.

Seruka also offers follow-up care, though ensuring that patients take advantage of this option is a challenge, as is the case in other MSF projects. Less than half of the patients attend the one-month follow-up visit, and one in 10 return one year later. Distance and cost of transport make attending follow-up appointments difficult, as 40% of victims live outside Bujumbura. Seruka will contribute towards the cost of transportation as needed so the patient can attend consultations. Lack of awareness of the importance of follow-up care can also prevent patients from returning. “Once they receive their antiretrovirals and the morning after pill, and receive medical care in the case of physical injuries, they do not see the need to come back”, said Dr. Rose Kamariza, an MSF doctor at the clinic.

Emergency shelter is available for those who need a place to stay. “Sometimes, by the time they finish the consultations in the center, it is too late to go home. Or maybe they feel too scared or shocked to go back immediately”, said Nyakuza, the MSF nurse. When patients need longer term shelter, MSF liaises with other organizations that are able to provide it.

If a victim wants to press charges against a perpetrator, a medical-legal certificate is issued in the centre, free of charge. In Burundi, medical-legal certificates are only valid if given after the patient has been to the police. As all the relevant details from the medical consultation are recorded in the patients’ files, if a rape victim goes to the police and decides to press charges at a later stage, the doctor is able to issue the certificate based on the consultation record. In the first semester of 2008, 212 medical-legal certificates were requested by rape victims at Seruka: 26% of the total number of victims coming for care. Medical-legal certificates issued by MSF doctors are not always accepted in Burundian courts, however. “Sometimes they request certificates signed by a government doctor, but there is nothing in the law that requires that”, explains Joseph Mugigi, of Ligue Iteka, the Burundian human rights organization. If the victim wants to pursue legal action, they are referred to local organizations such as Ligue Iteka or Aprodh, or international nongovernmental organizations such as Avocats Sans Frontières, which provide legal follow-up.

The MSF team in Seruka treated 6,800 victims of sexual violence between 2003 and 2008. Every month, about 130 new victims of sexual violence seek care at the center; 81% arrive within 72 hours of the rape. “For the past four years, we have been communicating strongly about the need to seek medical care and to do it within three days”, said van Baelen. A recent survey by MSF in Bujumbura showed that 80% of the people interviewed were aware of the importance of seeking health care within 72 hours of the attack.

Behind the success of raising awareness about care for victims of sexual violence is a team of health promoters who work in the clinic and in the streets of Bujumbura. They have formed networks of women who were victims of sexual violence in different communities who help raise awareness of rape by giving testimonies, visiting women in the community and working as focal points for support. Every week, the health promotion team organizes activities in different communities. They hold morning sessions in the clinic for patients to tell them about the care they are about to receive. Information about Seruka and rape is also broadcast on the radio and highlighted during “16 Days of activism”, a series of events that takes place every December to highlight and address the issue of violence against women.

The expertise acquired by the Seruka team is shared within Burundi and also with MSF staff treating victims of sexual violence in other countries. A training program has been developed by the team and is offered to staff from other health centers in the country interested in providing care for victims of sexual violence.

Helping Children Who Survive Rape

“It was S. who did it to me. I was out in the fields looking after the goats with the other children. He arrived, grabbed me by my arms, took my clothes off, laid me down on the grass and raped me, in front of everybody. Then he ran away. He didn’t rape any other child, just me. I don’t know why he chose me. Today I just stay at home. I don’t want to go to the field anymore because I am afraid somebody will do this to me again. It hurts”.

Girl, 9 years old, raped by a friend of the family

The Seruka team has seen an increasing number of young patients visiting the centre. today, 60% of the victims have not yet turned 19 years old; half of these are under 12 years old. Babies and toddlers are not spared : 13% of all the victims are younger than five years old. “We didn’t open Seruka as a centre for children victims of sexual violence. But due to an increasing number of children, we are having to adapt the services to their needs”, said MSF psychologist Montanez.

A social worker helps support young patients as they go through their medical examination and psychological consultation. She explains to the children and their parents what is going to happen at the center and deals with any questions or concerns. While children are waiting to be called in for a consultation, she encourages them to play. “Often, children do not speak. if we take time to play before they go in for their consultation, they relax and feel more at ease. When they are called to see the doctor and the psychologist, they express themselves more easily”, said Maman Rose, an MSF social worker working with children.

Children and adolescents are not spared the stigma that often falls upon adults who survive rape. “What happens to school girls is so cruel, it is heartbreaking. They are ostracized by all their classmates. If they become pregnant, they can be expelled from school”, Montanez said.

Seruka Continued: Handing Over to the Staff

By mid-2009, Seruka will no longer be an MSF project, but the services provided to rape victims in Burundi will remain. the new association formed in July 2008 by Seruka staff members, ISV (Initiative Seruka pour les Victimes de Viol), will continue the work. By the end of 2008, ISV had 40 members and an elected board in charge of the main decisions about the future of Seruka. The staff currently working in Seruka will be employed by ISV. Contracts with donors are being finalized to ensure that Seruka has the funds it needs to continue the work.

To support the handover, MSF is providing on the job training for staff and will give technical support throughout 2009. “Seruka has a very strong foundation and is visible and well known by the public, and the quality of the services is widely recognized”, said Josiane Karirengera, a former health promoter who has been appointed as the new coordinator of the center. “This will allow us to overcome many barriers. But now that it is becoming a local organization, we will have to show the donors our expertise. Now it is important to communicate that the center is not closing. That MSF is leaving but we will still be here”.

To support this effort and to garner community support for ISV, MSF staff working in Seruka initiated a campaign against sexual violence in Burundi: OYA !, which means ‘no !’ in Kirundi. By the end of 2008, OYA ! had gathered 1,300 members committed to fighting sexual violence. Besides raising awareness of rape and showing the community that Seruka is not closing, OYA ! encourages activism against sexual violence.

“When we opened the project, there was very little awareness of rape in Burundi and no care available for victims. We wanted to set up a structure to provide care, but also to open a discussion about rape in society”, said van Baelen, the MSF project coordinator in Seruka. Despite growing awareness of rape in Burundian society, the availability of care for victims is still limited. “There are organizations focusing on sensitization, there is a lot of good will, but few actually providing medical care for victims”, said van Baelen.

Change in Profile, Change in Care

Since Seruka was launched in 2003, MSF teams have witnessed a marked change in the circumstances of rape and the profile of the aggressors in Burundi. Since the end of the war and through the post-war transition period, the number of assaults committed by non-civilians has decreased significantly. Today, an average of 90% of those seeking care at Seruka have been raped by a civilian. Of these, two-thirds of the rapes are perpetrated by somebody known to the family. Threats of violence with weapons and gang rapes, characteristic of the military conflict, have also decreased. The profile of the victim has shifted. At the beginning of 2004, most victims were adult women. Today, more than half of the victims have not yet turned 19 years old.

As the profile of aggressors and the circumstances of rape change, so does the response required. In 2004, medical staff at Seruka more often treated physical wounds and lesions, whereas now there are often less visible signs of the rape. As most aggressors are known to the victims, often neighbors, domestic staff or family members, returning home after being raped poses a new threat to the victims. Women therefore need protective measures such as safe shelter. The nature of psychological counseling is also affected by the circumstances of rape. Initially, the work of psychologists focused on external factors which were out of the victim’s control, such as the conflict and pervasive military presence. Today, the situation requires an examination of factors in or around the victim’s environment. As most assailants are never convicted and will often continue to live near the victims, this work is crucial to enable the victims to overcome the trauma caused by rape.

Read the full report: Shattered Lives