Emad: "Life will not be this way forever"

Emad, 27, fled war in Yemen to seek asylum in Europe. He lived in an overcrowded refugee camp on the Greek island of Samos for two years and five months before receiving his national identity card. Only then could he finally leave the island and begin his new life. He now works with MSF on the nearby island of Lesbos, where we provide medical and mental health care to the thousands of refugees stranded in inhumane living conditions. Here, Emad talks about his work as a health promotor with MSF and the people he has met in the camps.

This month in June it will be three years for me in Greece. I came from Yemen. I started working with MSF in Samos in May 2020 when I was still living in the refugee camp. For seven months, I worked as a health promotor in the camp and in the safe space MSF opened for high-risk people when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. After that, I worked as a receptionist for MSF for two months. For the last three months, I have been living and working with MSF in Lesbos. I really like the job. You come and [tell] people what you know, what you experienced. You tell them everything to give them awareness.

Maybe they’re a doctor, maybe they’re an engineer, maybe they’re someone that has knowledge—but the conditions [in the camps] kill all of that. The mind is tough, the body is tough, but you cannot think there. As a health promoter, you’re the one who is helping all of that. [This job] shows me how I am helpful in the community. I love it. I have that spirit and I have that energy to make someone happy.

It’s very important to have a former refugee, someone from the community, [in this position], because you know the culture, you know the traditions. You know what is good for this community, how to avoid what they don’t like, the best way to communicate a message. Your experience also teaches people that life will not be this way forever. People always say “we will die here,” because the conditions are so heavy on them—mentally, physically. But I know how to enter their heart and their minds, because yesterday they saw me sleeping next to them and today [I am here].

I don’t know what I’m going to do in the future, but at the moment I’m really happy. I’m working at a [job] that I really like. [Maybe] I’d like to one day work as a health promoter in another country with MSF or another organization. I’d like to learn more, study more. As a refugee, there is a limit to what you can dream for, but you have to do your best—I am doing my best.

I’m learning from my colleagues. Everyone is from different countries and everyone is [learning from each other]. Sometimes to study from a book is not enough—you have to learn from life. Everyone has experience, everyone has ideas, everyone has opinions. Give your time and give your mind to someone. When you stand next to that person, when you talk to them, they will feel happy. They will feel that love and think, “Oh, there is someone who wants to talk to me. I am again a human.”

I want to tell the people who read this: Don’t hesitate to help someone. Whatever it is—smiling, laughing, listening, shaking hands, hugging, sharing—never hesitate to do something for people that need help. Because tomorrow, who knows? You might also be in need.

Hassan: "We live as if we are in a prison"

Hassan, 47, and his family have been internally displaced multiple times since war broke out in Syria 10 years ago. He currently works with MSF in Idlib governorate, where we provide medical care, distribute hygiene items, and build latrines in camps for displaced people. Here, Hassan shares about loved ones he’s lost along the way and the challenges facing hundreds of thousands of people living in northwestern Syria today.

In 2012, I had to flee my home for the first time. [That same year] my mother passed away. But I couldn’t be there at her funeral because the Syrian army was bombing the area. I was 17 kilometers [about 10 miles] away from my village and couldn’t lay my eyes on her for the last time and say goodbye.

In 2015, I went to Iraq for work, where I was arrested and locked up for 18 days. While I was in Iraq, my family— who stayed in Syria—had to flee for a second time. So I never returned to that home.

The third time, we took refuge in a house on a farm. We ate together with insects—the locusts were sharing our food. We remained there for one and a half months. During the month of Ramadan, the village was bombed and the houses where my brother and I lived were hit, so we moved to Idlib city.

I had to travel to Turkey for work towards the end of 2015, when Idlib came under heavy bombing. My children were at school and were traumatized because they couldn’t find each other. I was extremely frightened until they made it home. My brother lost his two children in bombings within 35 days of each other. My daughter, who witnessed that, developed nervous episodes and she started fainting constantly. Life became meaningless. This has impacted me the most.

In 2016, my son, who was still very young, couldn’t sleep and used to say, “The plane is here!” He lived in horror and fear and had psychological problems due to the bombing.

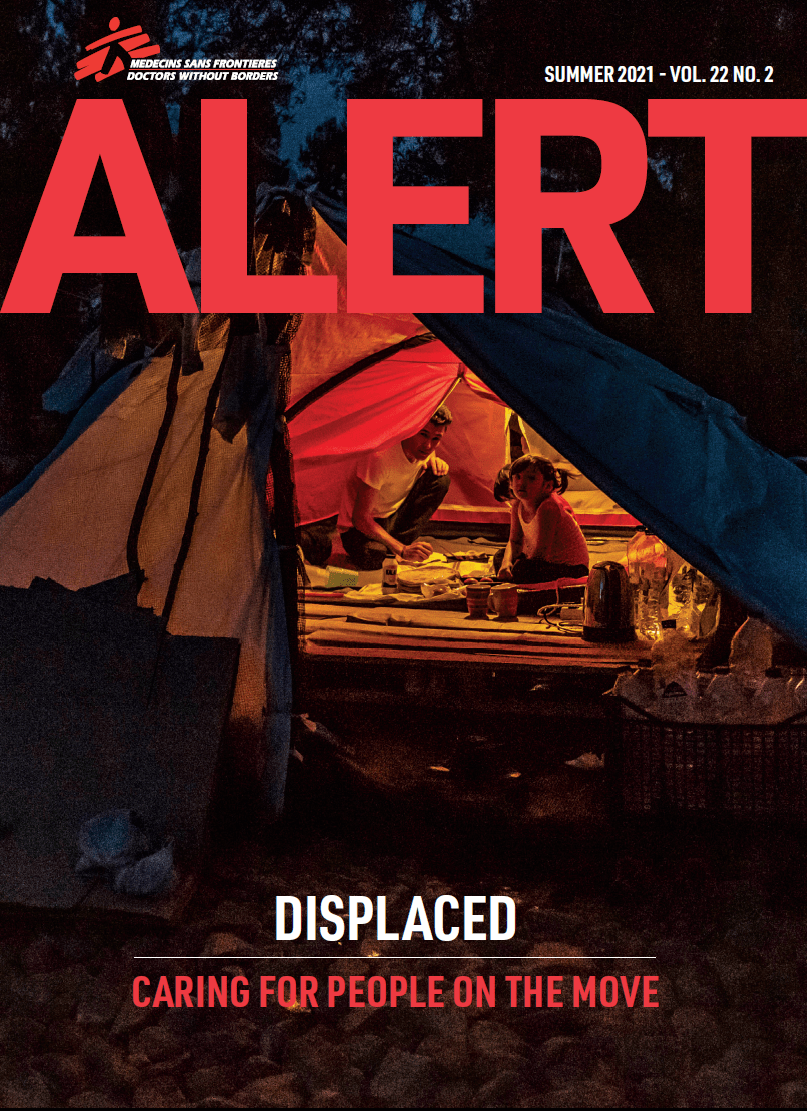

I started working with MSF in 2016 as a logistics specialist—before the war I worked for an electric company. Soon after, I moved from Idlib to Al Dana [about 23 miles north of Idlib]. There we had to go to the fields during the day to take shelter from the bombing. Sometimes we had to sleep at nearby chicken farms to escape airstrikes. My wife, my children, and I slept outside under the trees.

In 2020, just before Ramadan, the bombing became unbearable, so we moved on the first day of Eid Al Fitr. My children were supposed to enjoy Eid, but instead we had to move. We lived in two rooms underground in a place that doesn’t see the sun. We stayed for a whole month.

I currently live in Al Dana city. The biggest problem we face as a family is that, although my oldest son is studying dentistry and my two daughters are studying medicine, they will not have any certificates because their universities are not recognized. There is no support for education. When I had children, I could no longer see the future through my own eyes, only through theirs. I see them go out there to study and work hard, but in the end, what kind of a future can they plan? We live as if we are in a prison.

At work we visit the tents where displaced people are staying—mostly for two or three months, although some of them have been in the camp for seven or eight years. They live under a piece of cloth that doesn’t protect them from the summer heat or the winter cold. There are 400 camps without water. Bread has become a dream for many people. I’m in constant communication with the displaced people who live in the camp. They feel comfortable with me, because, who are these people? My brother, my cousin, my uncle. I consider them my family. Even when I can’t help, they still express their concerns to me.

Sometimes I feel helpless in the face of what I see. Their pain is mine. When I go to the camps and I don’t see any latrines, I imagine my family and myself there, and this breaks my heart. When I tell my managers at work about the situation in the camps, I see the tears in their eyes. I'm 47 years old, but people would think I’m 55 or 60. We’ve had a very tough life.

Nur Boshor*: "Treat us as human"

Nur Boshor was one among the hundreds of thousands of Rohingya people who fled to Bangladesh in 2017 following a targeted campaign of violence led by the Myanmar security forces. Four years later, nearly 900,000 Rohingya are still living in what has become the world’s largest refugee camp, in a sprawling settlement in the Cox’s Bazar district of Bangladesh. Rohingya refugees are not allowed to hold jobs, and can only earn a very small wage as volunteers with organizations working in the camp.

Nur Boshor works as a daily volunteer with MSF’s outreach team. Here, he explains why Rohingya volunteers are a vital part of the team and expresses his hopes to return home in the future.

In 1962, the army took power in Myanmar and enacted martial law. From that time, gradually they started neglecting us and torturing [us]. In 1974, for the first time, they denied our citizenship status. Torture and ethnic cleansing increased. My family tolerated it until 2017—when we finally decided to leave. We left our belongings, land, houses—everything. The Myanmar army at that time established checkpoints on the [route] and indiscriminately fired at us. We lost many souls back there while fleeing.

The situation in the camps is [getting] worse day by day. People have no jobs. People depend on rations from food programs and [are given] only 1,017 Bangladeshi taka [about US$12] per month for a family. How can a family survive with this small amount? We can only afford rice and lentils—fish, meat, or much-needed medicines are far [too expensive].

I worked in the development sector back in Myanmar. A few days after [I arrived in Bangladesh], I joined MSF as a daily volunteer. Rohingya people have their own language and culture. Only a Rohingya can understand what another Rohingya says and wants. When we were in Myanmar, many pregnant women died in the hospital just because they could not express their feelings and condition properly to non-native speaking doctors. Gradually, people became afraid of hospitals and clinics.

Now [in Bangladesh] Rohingya volunteers [with MSF] go door to door and discuss health issues, try to explain the importance of seeking medical assistance, and try to remove their long-held fear of doctors and hospitals. These things are only possible from a Rohingya volunteer.

Many [people I know] want to go back to Myanmar, as they face insecurity in the camps. I am also keen to go back to my soil. [But] not now, as the situation is not under control there. We would be facing horror again if we go. We are refugees, yet human. We have dreams. We need medical assistance when we are sick. We need food when we are hungry. We need shelter. I beg of everyone from the outer world to treat us as human. We want repatriation as soon as possible. We want to go home.

*Name has been changed

Fowsia: "There is not one person who wants to stay in a refugee camp forever"

Fowsia, 31, is an auxiliary nurse at MSF’s 100-bed hospital in Dagahaley—one of three sites that make up the Dadaab camp complex, which hosts more than 430,000 refugees, primarily from Somalia. Like many people in Dadaab, Fowsia has lived here most of her life. In April, the government of Kenya and the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) announced plans to close the camps by June 2022, leaving many people uncertain about their future. Here, Fowsia talks about her experience living as a refugee for almost 30 years, and her thoughts on closing the camps.

I was two years old when I left Somalia. I don’t remember anything about it, but my mother has told me tales. After the civil war broke out, my uncle was killed in the fighting. So my family decided to migrate to Kenya to seek asylum. It took about four days on foot to reach Kenya. The journey was hectic. On our way to Kenya, we were robbed of our belongings. When we arrived, we were registered by UNHCR, given some food and a tent to construct, and got settled in Dagahaley camp—which, at the time, was just trees and dust.

I completed my primary and high school education here. I have a diploma in community development and am currently doing a degree in educational studies. I like what I am studying right now—education transforms societies, through education everyone’s future gets brighter—but in the camps, we don’t get to choose what we study. We don’t have resources, like school fees, so we depend on scholarships provided by organizations, and those scholarships determine what courses we can take. We don’t have a choice—we just take what comes our way.

I’ve worked with different organizations in the camp since high school—as a warehouse assistant, as a child protection officer, and now with MSF as an auxiliary nurse in the maternity department. What motivates me is serving the community. It is important to hire people from the local community. If you hire someone from a different community, they may have communication barriers. It also creates job opportunities and gives us a means to sustain ourselves.

Being in the camp is like being a bird in a cage. After being here for so many years, you don’t belong to anywhere, so I welcome the idea of closing the camps. There is not one person who wants to stay in a refugee camp forever. But the announcement [that the Kenyan government plans to close the Dadaab camps] has created a lot of concern in the community and uncertainty for the future.

There are no good options. I don’t want my children to grow up in a refugee camp. If you are resettled in a third country, you just go from one country where you don’t belong to another. If you go back to Somalia, you have to start afresh—you don’t have a place to stay; you don’t have a home. For my children, Somalia has no quality education, no medical services, no basic amenities. There are people who went back to Somalia when the first wave of repatriation started in 2016, but because of the insecurity, drought, and famine those people are coming back to the camp.

Being a refugee is not a choice, it is by circumstance. People like me are forced to flee their home countries because of civil wars. We would not like to remain as refugees forever. We cannot be stateless for any longer. I would like to be someone who has a place to call home.