Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) launched the Access Campaign in 1999, the same year we received the Nobel Peace Prize. The birth of the campaign happened at a pivotal moment in public health. Beginning in the mid-1990s, treatment for HIV/AIDS with new, effective drugs known as antiretrovirals (ARVs) was producing dramatic results for the patients who could afford them. As a result, mortality rates from AIDS—long considered a death sentence—fell sharply and steadily.

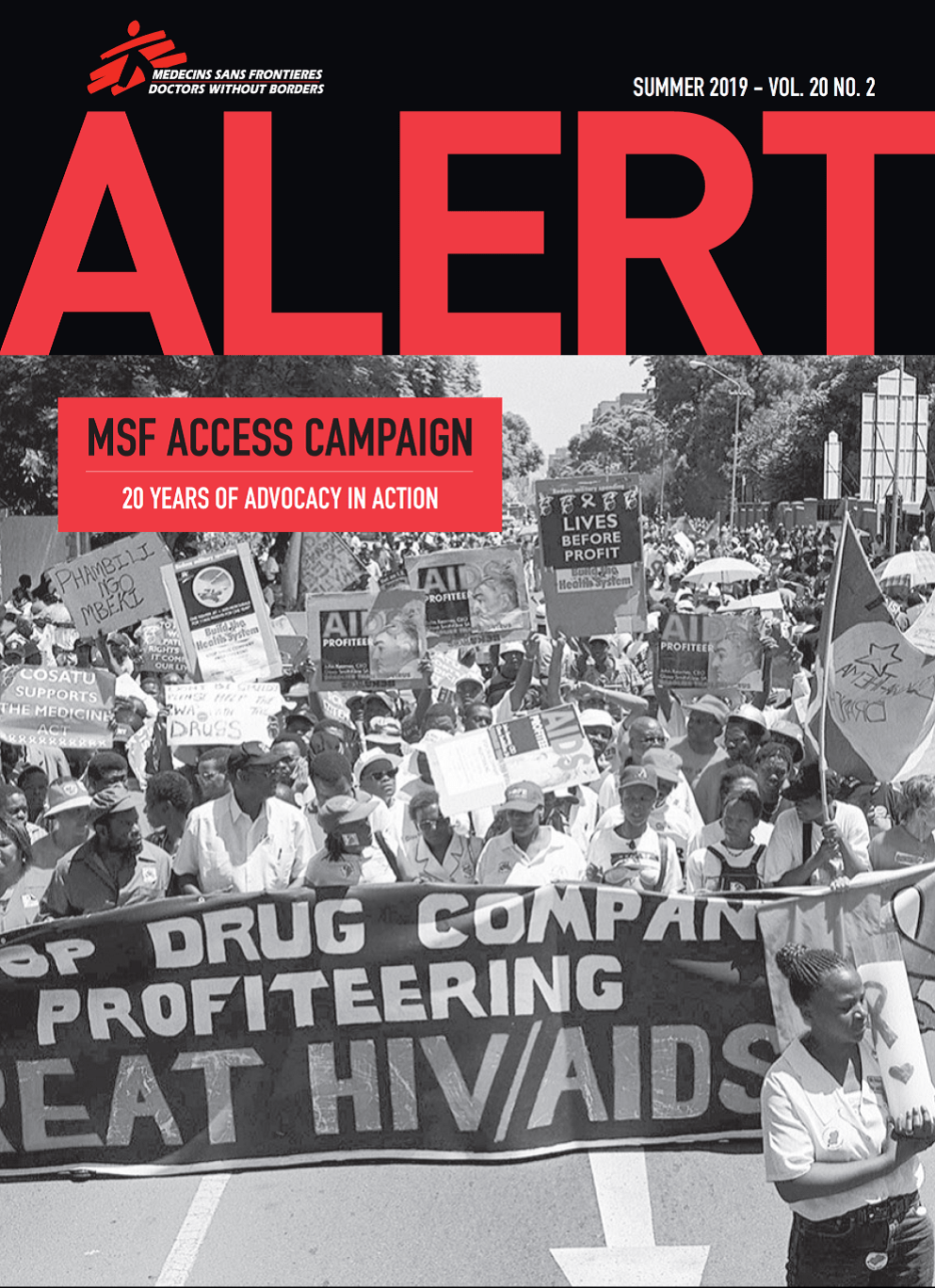

But in low- and middle-income countries, exorbitant drug prices charged by pharmaceutical corporations kept ARVs out of reach for the vast majority of people living with HIV. As a result, the number of AIDS deaths rose precipitously in countries like South Africa, where in the late 1990s and early 2000s as many as 250,000 people died from the disease yearly. The lesson was clear: if the best medicines and tests were available to people everywhere, many more lives could be saved.

It was for this reason that MSF launched the Access Campaign, which in 1999 was known as the Campaign for Access to Essential Medicines. As part of the international MSF movement, the Access Campaign works to bring down barriers that keep people from getting the treatment they need to stay alive and healthy. The campaign advocates for available, affordable drugs, tests, and vaccines that are suited to the people MSF cares for and adapted to the places where they live.

Dr. Bernard Pécoul was a co-founder and the first director of the Access Campaign when it was launched in 1999. He is now executive director of the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi), which grew out of the campaign’s pioneering work. Here, he remembers the early challenges and successes.

What led MSF to start the Access Campaign?

Unaddressed medical needs led to the start, and the need to understand how to overcome the problems that stood in the way of better treatment for our patients.

One example: In the 1980s and 1990s, MSF was confronted with sleeping sickness in Uganda. We knew existing treatments were terribly toxic—based on arsenic—and could kill 5 percent of people treated. But we had no choice [but to use it], as the disease is otherwise 100 percent fatal! A much better option existed, but this drug was no longer being produced, so our programs couldn’t access it.

For other diseases like kala azar [visceral leishmaniasis], meningitis, and shigella [a bacterial disease closely related to E. coli], we were confronted with a lack of products, or a lack of access to products, or both. After the twenty-fifth anniversary of MSF in 1996, we created a working group to understand the causes for this.

We knew we had to do something. But what? And how? The first step was to understand exactly where the problems were and gather the expertise so that the access and research and development (R&D) barriers could be confronted and overcome—that was the role for the campaign.

What did the creation of the Access Campaign mean for MSF?

As a medical organization, MSF was not assessing the political or legal environment that governed access to medicines. We were logistically oriented and had made great progress in bringing medicines and vaccines to the field—we knew how to purchase and deliver. But we needed to address the situations when we had nothing to purchase, and nothing to deliver.

Take HIV. It was obvious that intellectual property (IP) was a major challenge, pricing treatments out of reach. Addressing IP barriers was a priority. But for sleeping sickness or leishmaniasis, the issue was a lack of R&D. You cannot address both IP and R&D with the same tools and response. The campaign was the structure that developed a deep understanding of the problems, and then proposed solutions.

What were the Access Campaign’s first achievements?

Getting rid of toxic sleeping sickness treatment was a first success. On a trip to the United States, I suddenly saw an advertisement on TV for a hair removal cream containing eflornithine, the drug we had tried and failed to access for many years to treat sleeping sickness. So this lifesaving drug wasn’t available for people at risk of dying, but could be bought as a cosmetic product!

We took the story to The New York Times, and to [the CBS news program] 60 Minutes. This was the beginning of a long process that led to massive improvement in sleeping sickness treatment.

The campaign also led on malaria. In the 1990s, MSF programs were starting to observe that chloroquine [a drug introduced in the 1940s for the treatment of malaria] was not doing the job. But there was reluctance to change the status quo. MSF and Epicentre [MSF’s medical research arm] conducted a series of studies to document resistance to chloroquine, and on that basis the campaign came up with a strong message: “ACT NOW” to change treatment. [We wanted to] make artemisinin-based combination therapy [ACT]—newer, more effective malaria drugs—available, and do it everywhere. This campaign put pressure on the World Health Organization and led to the adoption of ACTs.

For HIV, the campaign also had a role in challenging the status quo. Publicly, [we led the] drive to reduce the price from $12,000 for a year’s treatment down to $1 a day. And within MSF, this contributed massively to overcome hesitancy to treat HIV, which previously was so expensive and complicated it seemed unfeasible.

And, by convening an expert group of idealists that thought we could do things better, the campaign also led to the creation of the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative [DNDi, a non-profit drug research and development organization that develops drugs to treat neglected diseases]. After investigating the problems on the R&D side, we realized that to develop solutions we needed to create a separate initiative, one that could demonstrate a different model, a different way of doing R&D, and that could deliver. DNDi’s achievements are also the campaign’s.