Since March 2020, the United States government has deported more than 600,000 people under the Title 42 order, which exploits the COVID-19 pandemic to effectively close the US border and send asylum seekers and other vulnerable people back into danger in Mexico or their countries of origin. In March 2021 alone, more than 104,000 people were deported.

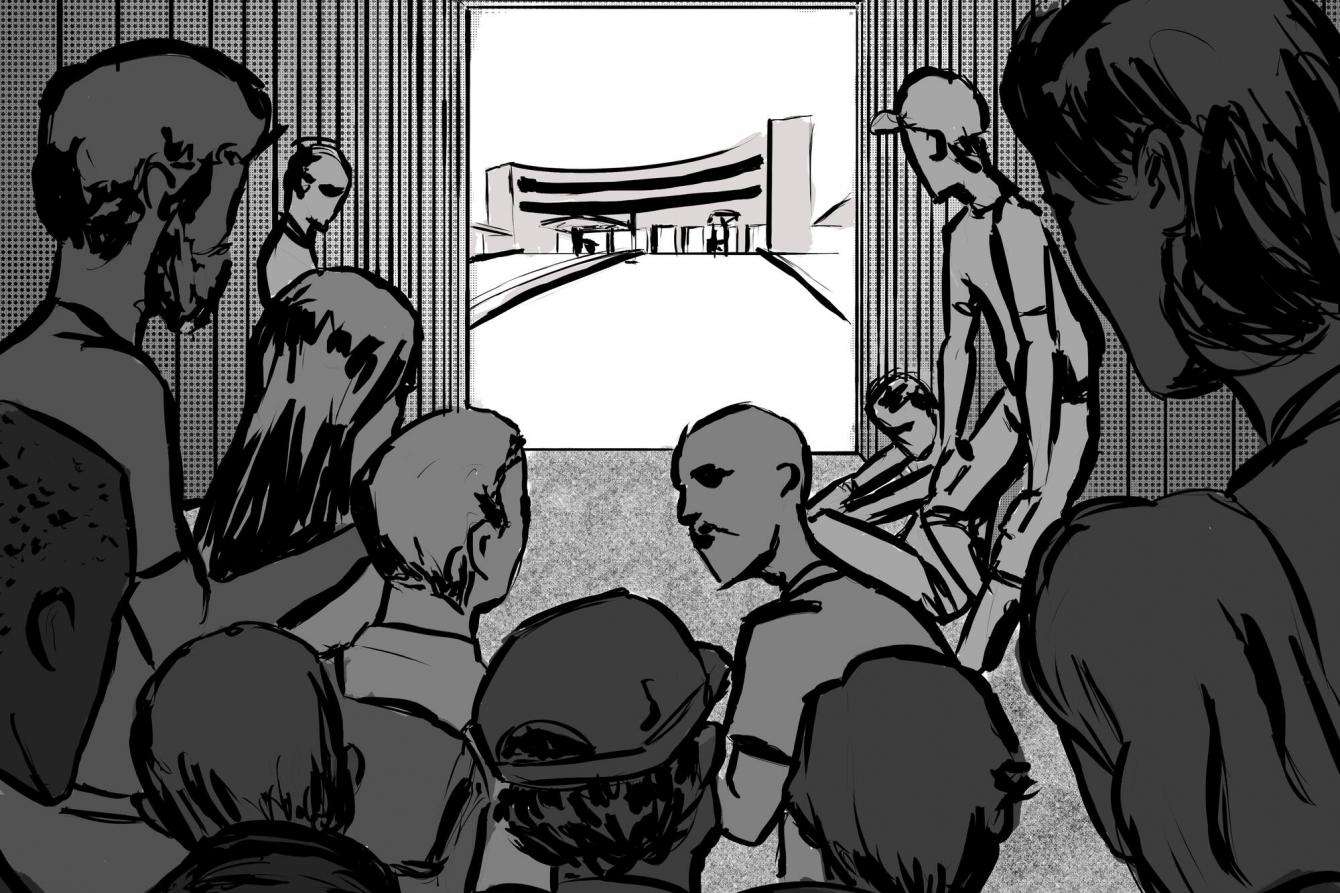

As a result, thousands of people are now stranded in dangerous cities along the Mexican border with no legal recourse and no way home. In April and May, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) interviewed migrants and asylum seekers in Ciudad Juárez, Nuevo Laredo, and Coatzacoalcos, Mexico. Some are still trying to gain entry to the US, while others have already been deported under Title 42. All of them speak of the fear and trauma they have experienced on their journeys.

Marcela: “I felt like the world was ending, like I didn't want to live anymore.”

Marcela, 26, fled Guatemala. She managed to reach the United States but within hours she was deported to Ciudad Juárez, a place she’d never been. She is now living in a migrant shelter.

“I am from the Yuki Yuna indigenous community. I left my country because I was raped by three men, and because of poverty in my community and also because I no longer have a home with my parents.

[To get into the United States] we were placed in trailers with about 250 people, without any food or even knowing where we were. I was traveling with my sister.

When they left us on the bridge [over the Rio Grande] and I entered the US, I was so excited that I had already arrived there, happy and joyful. But the people who caught us—the immigration authorities—told us after taking our fingerprints that, no, people were not passing through.

Then they deported us—took us over the bridge and left us there. We entered the United States around 6:00 p.m. and they deported us at 10:00 p.m. I felt like the world was ending, like I didn't want to live anymore.

I cried a lot and then some female companions from another country said, ‘Come on, there is a hotel here.’ There we heard that [the hotel] was a dangerous place; that there were bad men there.

We left with those women who took us, and we found a pastor who helped us. He helped us, and they dropped us off here at this shelter."

Carlos: “I remember him saying, why did you come to my country?”

Carlos, who is middle-aged, fled gang violence in El Salvador with his son six years ago. First they settled in Guatemala, where he and his son lived for some time. He is now trying to reach the US, where he hopes to find better economic opportunities. He has tried unsuccessfully to cross the border twice, and is now in Ciudad Juárez.

“Violence was increasing [in El Salvador] to the point that it was no longer safe for young people, children, or even adults to live in my country. Six years ago I went to Guatemala so that my son could build a life for himself—he was still young. Now he is 23 years old, thank God, and in Guatemala he met a woman who is now his wife. I already have a grandson; my son is already a father.

I decided to emigrate so that I could buy things that I couldn't have in my country. I wanted to emigrate to the United States. I have already been here in Mexico for [months], where I have been working until now. [The smuggler] who was going to pass us through the desert said that the best option was [through] Chihuahua.

The first attempt was before May. I don't remember the date, but we walked for almost 14 days through the desert. He really didn't know [where he was going], we had to guide him by GPS and Google Maps because he didn't have a phone. Anyway, thanks to God, after 14 days we got as far as Texas, to the first little town, but when we arrived the first time we made the mistake of lighting a fire.

We were on a ranch, and we lit the fire because it was cold at night and the owner of the ranch was about 500 meters [about 1,640 feet] up the road. We never imagined that this rancher was going to call immigration, but they arrived at night and took us back to Mexico.

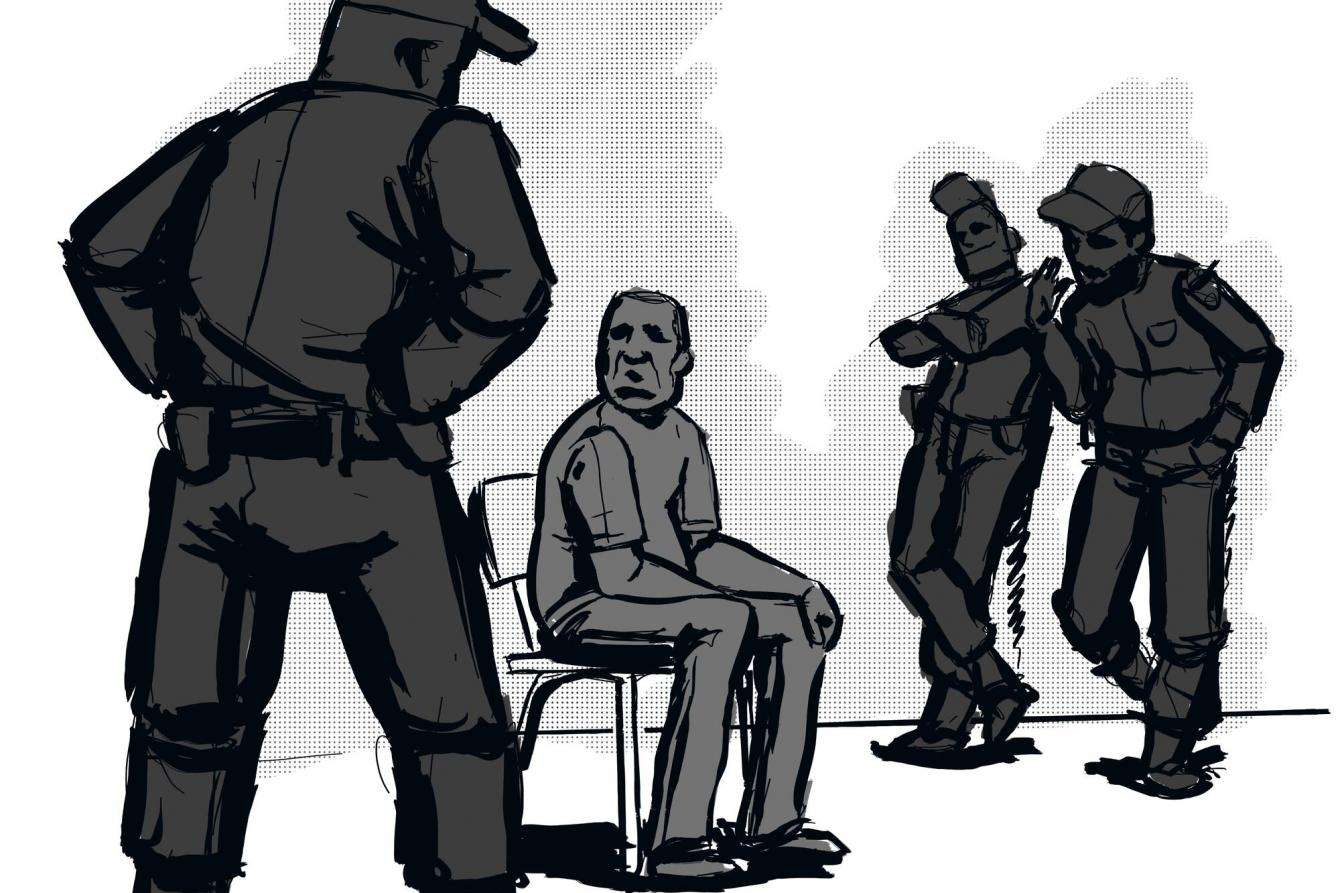

They are sending people back very quickly. They don't even ask why you are actually migrating to the United States. There is hardly any paperwork: they just take your information, your photograph, your fingerprints, put you back in the holding cell and then, after 35 hours, they release you [in Mexico]. They dump you in a place you did not enter from and a bit further away, so it's more complicated. Frankly, it is inhumane treatment.

The second time, I tried again, on May 1. I was in the desert for nine and a half days. As we already knew [the way], it was easier for us, but we felt the fatigue and the dehydration more. This time when they caught us as we arrived at the town of Van Horn, the treatment was very bad.

The border agent or border police treated me very badly and it was really kind of aggressive verbal treatment, very unjust and I think it was also racist. A policeman had a go at me, he said, ‘Why did you come here if you could work there on the other side, what reason did you have? Why did you come to my country?’ I remember him saying, why did you come to my country?. And the other officers made fun of me, so yes, I say that, maybe not all of them, but they have racism in their minds, in their hearts.

They get you out of the holding cells as quickly as possible due to the risk of COVID transmission and also due to the expenses. They catch many people every day, so the cost is a factor, right?"

Maritza: "I do not want to return to my country as it is very corrupt.”

Maritza, 35, is traveling with her husband and son. They fled Honduras because of gangs. They were deported from the US to Ciudad Juárez and hope to be able to cross the border again, since they cannot return to their country.

"I do not want to return to my country as it is very corrupt. You cannot work, and if you do work they do not pay you enough. The extortion drives people, and my husband had problems there because the gangs were demanding that he join the gang.

Immigration caught us in Palenque, Mexico. They asked my husband how much money he had and he told them 1,000 pesos [about $50]. ‘Leave the money here under this piece of paper,’ they told him, and that's that. And they made him sign something and then they came to me.

‘Hand over the money,’ they told me. ‘I only have 500 [pesos],’ I said, ‘but it's all I have for food for my son.’ ‘Leave the 500 there, and you can go; put the money under this paper and that's that,’ they said. It was all the money I had for food for my son and they took it from me.

Through a relative we were able to contact a coyote, or people smuggler, in Palenque to bring us up here. We traveled with him but I don’t even want to remember that part of the route.

And now I am sitting here in Ciudad Juárez because I was deported. I entered the United States, but then they took us in a truck to an office and then they left us for five days locked in a holding cell—a very cold place—with my sick child. He got sick many times and I wanted them to let me out. I prayed to God.

They told us they were going to let us out but they didn't tell us where. We landed here in Mexico and were told we were coming to immigration. At the immigration processing center they treated us very well, thank God—they gave us water, food and everything, milk, diapers. We were well-received, thank God, and then they brought us here. That is how we were brought to this shelter that night."

Paolo: “My country is dangerous—I can't go back there. Ever.”

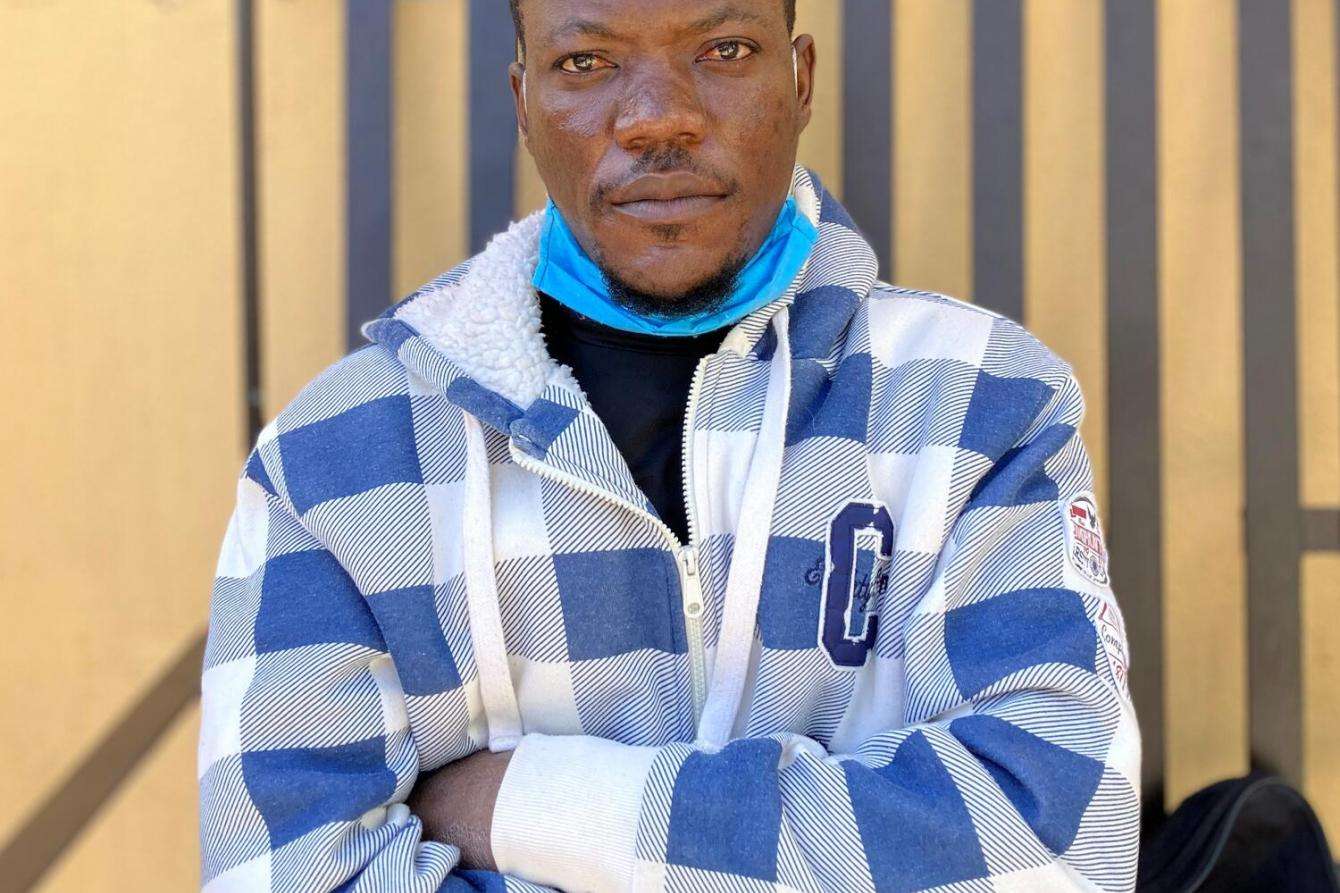

Paolo fled Togo, in West Africa, because he feared for his life. He has been traveling for two years and traveled across the Americas in his attempt to reach the US. He is now waiting in Nuevo Laredo to be able to cross the border legally.

I want to go to the US. I have problems in my country, and when I reached Bolivia, I didn't know anybody. Spanish was difficult: nobody talked to me. I suffered there, so I left.

In my country if you are gay, they don't accept it. People came to my house. They came to my home, they beat me, they cut me; they wanted to abandon me in the forest. They wanted to take pictures and publish them on social media. I don't know where my partner is. Before the pictures were uploaded, I ran away. My country is dangerous—I can't go back there. Ever. They could kill me. My family told me that God was punishing me.

The US is better than here, than there. I want to cross in a legal manner. I don't have a lawyer; I only have one friend here. I didn't tell anybody that I was leaving my country.

I haven't had any problems with crime. Once, four men asked me and my friend where we were from. We told them that we were from Africa, so they let us go. We told them we were looking for aid.

My friend has a job here. We are trying, but the border is closed. We'll wait for three months, six months, waiting for the border to open.

It's better to cross to the US. I don't speak Spanish, so I feel quite alone, I can't speak to anybody. My friend, the guy that helped me on the road, speaks Spanish."

Bella: “Why would I go back to my country? That is why one takes these paths of suffering.”

Bella, 36, is from Santa Bárbara, Honduras. She recounted her story in Coatzacoalcos, where migrants attempt the hazardous ride on “the Beast,” a train that crosses Mexico.

"I used to sow beans and corn. I went to the fields every day to earn a living. But seven years ago, the father of my children was killed.

It is not easy. My eldest two children are already married and I have my 12-year-old daughter. She is in sixth grade. My daughter told me: ‘Mommy, I want to go to school,’ and I told her, ‘I can't [afford it].’ That was what made me decide to come here, even with the suffering.

When the [Mexican] border agents chased us, we jumped into a ravine. That's how I lost my other pair of tennis shoes. The ones I am wearing now are of no use; I am just walking on ‘las garras’ [bare feet], as we say in Honduras.

These paths are not easy. I don't have a penny to my name. Sometimes I ask my friends for a little water because I don't even have enough for water. I think I'm going to catch the train here, but I'm going to stay in Monterrey to earn a little money and work my way up.

There it costs $5,500 [to pass illegally into the US]. If I don't make it, I will stay in Mexico. The important thing is that there is work. All I know is that my children need me and that my mother needs me, and that gives me the strength to carry on.

I found this backpack on the train track, the bag I was carrying [before] was hurting my fingers. I have not found any shelters, we went to the migration house further down and they told us that it was already full. We slept in the street with a group, on those stones.

I am very afraid that they are going to catch me and send me back to Honduras again. Why would I go back to my country? That is why one takes these paths of suffering."